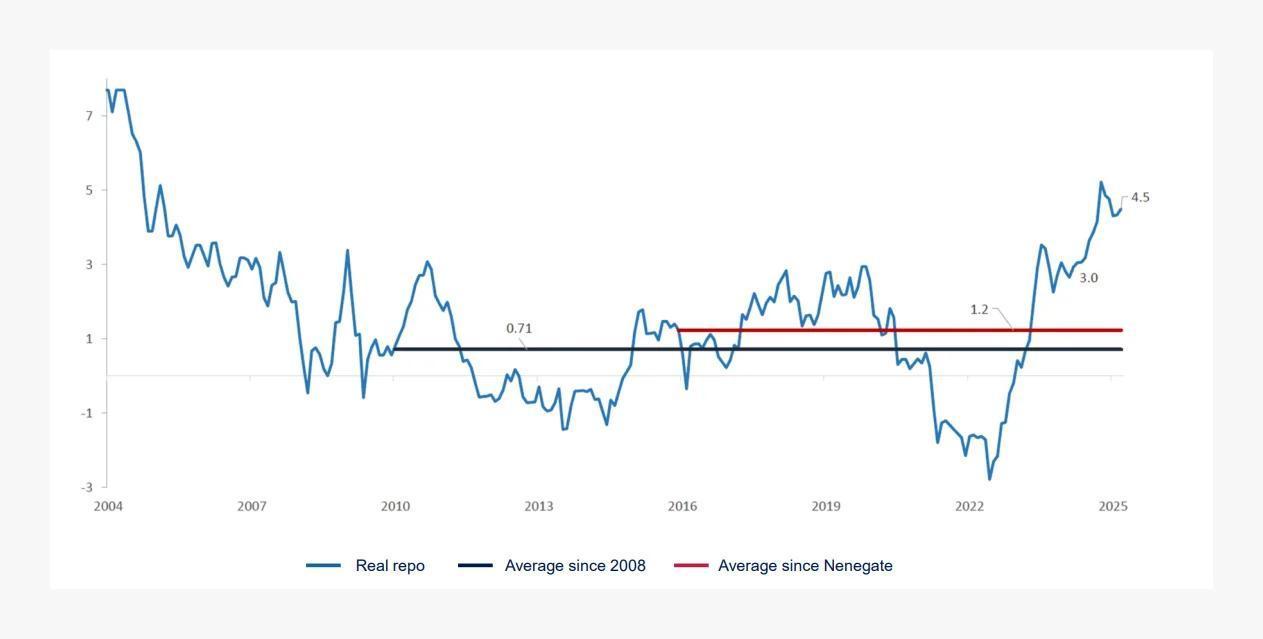

Africa-Press – South-Africa. South Africa’s real repo rate has been, on average, 0.5 percentage points higher since the ‘Nenegate’ scandal in December 2015 than the average since 2008.

This has translated into billions of rands in additional debt-servicing costs for the government, with it now paying over R1 billion every day to service its debt burden.

The relatively higher interest rates come as a result of government mismanagement of the fiscus, which has forced the Reserve Bank to compensate with more restrictive monetary policy.

Former President Jacob Zuma’s removal of Nhlanhla Nene as Finance Minister in December 2015 for his resistance to state capture has become emblematic of the mismanagement of the state’s finances.

On 9 December 2015, Zuma replaced Nene with ANC back-bencher David van Rooyen, with markets reacting extremely negatively.

The rand plunged by 5.4% in a single day versus the dollar, with the JSE Financial 15 Index falling 13.36% and over R165 billion in value was wiped from the exchange.

South Africa’s benchmark government bond, the R186, began the week trading with a yield of 8.6%. By the end of the week, the government was paying 10.4% on its debt.

After consultations with business leaders over the weekend and pushback within the ANC, Van Rooyen was removed as Finance Minister and replaced by stalwart Pravin Gordhan.

While lasting only a weekend, the incident became synonymous with the extent of state capture in South Africa and the willingness of malicious actors to get their hands on the National Treasury.

‘Nenegate’ has also become emblematic of the broader mismanagement of South Africa’s fiscus, which has been a major driver of the country’s poor economic growth and its elevated interest rates.

Since this scandal, South Africa’s real repo rate, which is the inflation-adjusted level of the repo rate which the Reserve Bank controls, has averaged 1.2%.

This is around 0.5 percentage points higher than the average real repo rate since 2008, indicating the impact of financial mismanagement on interest rates.

The graph below, courtesy of Melville Douglas, shows South Africa’s real repo rate and compares the average since Nenegate with the average since 2008.

Fiscal mismanagement drives interest rates higher

The government’s financial mismanagement has pushed interest rates higher in recent years, as the Reserve Bank has had to counteract the country’s elevated risk premium to attract investment into South Africa.

It is estimated that this compensation translates into interest rates having to be around 2% higher than neutral levels.

Worryingly, the gap has only widened in recent years as South Africa’s economy stagnated and the state’s financial health deteriorated.

Since 2007/8, the government has failed to run a full-year budget surplus, with state spending skyrocketing and economic growth stagnating.

This resulted in the government building up an immense debt burden, which now sits at over 76% of GDP.

As a result, the government’s credit ratings have deteriorated into sub-investment grade or junk status, prohibiting many global pension funds and investment schemes from investing in South African assets.

This resulted in significant outflows from South African assets over the past few years, significantly weakening the rand and further limiting economic growth.

The state’s mismanagement has pushed the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates relatively elevated to attract capital to South Africa and prevent a disorderly weakening of the rand as the country’s financial standing deteriorated.

Reserve Bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago explained that South Africa’s country risk premium is one of the main drivers of interest rates, besides inflation.

“I hope you will also have noticed that the second-biggest driver of interest rates is country risk,” Kganyago told the National School of Government in a recent speech.

He explained that the consistent rise in debt relative to GDP has increased South Africa’s risk premium significantly.

This risk makes the country’s assets relatively less attractive to investors than those in other countries, weakening the currency and potentially driving inflation higher.

To compensate for this, the Reserve Bank’s MPC keeps interest rates elevated to make local assets more attractive to investors by increasing the returns on offer. This attracts capital to South Africa and bolsters the rand, limiting imported inflation.

“If there were widespread confidence that debt levels were heading lower, this would create space for monetary policy to support growth through lower interest rates,” Kganyago said.

“All the drivers point in the same direction: credible fiscal consolidation would lower country risk. Improved investor confidence would also help the rand, which eases inflation.”

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press