Africa-Press – South-Africa. It can be said that South African leaders have looked at the current global balance of power and decided to pursue tightrope relations with both the Russia-China axis as well as the US and the West, writes Bob Wekesa.

The sensational naval exercises by South Africa, China and Russia – dubbed Mosi II – concluded late last month without mishap in the waters of South Africa’s Indian Ocean. But on the geopolitical battlefield, the war games have thrust South Africa into choppy waters. What does this tell us about South Africa-U.S. relations going forward?

A potential analytical framework for analysis of South Africa-US relations post Mosi II is the perception categories of optimism, pessimism, and pragmatism. In a recent analysis, I used this approach and found that Africans were somewhat optimistic towards the US economically and pessimistic on political matters. In foreign policy analysis, a perceptions approach is well placed for making sense of a development for which facts and data are not readily available or in flux.

Based on a three-dimensional perception analysis, South Africa and the US are entering an escalated period fraught with uncertainty. “Escalated” because the relations have not been on an even keel over the years, reaching their nadir during the Donald Trump administration. The differences are only likely to intensify. For instance, in 2022, South Africa abstained from voting on a UN resolution for the condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine even after lobbying for African nations’ support of the motion by the West. Thus, what are the reasons for the conclusion that relations are on fraught and uncertain course?

Standing its ground

In the naval drills, Russia and China successfully courted South Africa while the US tried unsuccessfully to woo South Africa the other way. If the US was optimistic that leaning on South Africa would succeed, it was mistaken about the limits to which its influence could reach. A pragmatic South Africa was prepared to stand its ground to uphold its avowed sovereignty in decision-making.

It is quite probable that the US will seek to retaliate in some form or shape – a case of US pessimism towards South Africa. There has been no shortage of voices of opposition and disappointment towards South Africa from the US and the West more broadly. But the most significant indication of action to punish South Africa is Resolution 145 submitted to the U.S. House of Representatives by Republican congressmen from New Jersey and California.

The resolution is “calling on the Biden administration to conduct a thorough review of the United States-South Africa relationship”. Doubts have been expressed about this motion passing just as the failed “Countering Malign Russian Activities in Africa Act” of April 2022.

The more important point is that the new motion is a bellwether for the kind of frustration in Washington that may trigger plausible vengeance. US officials in Washington and Pretoria must be asking the question: is South Africa an ally or a foe in our battle with Russia and China? Coincidentally, the naval drills were under way while the Republican right-wing senator for South Carolina, Lindsey Graham was on a tour in South Africa. Graham criticised the war games and is likely to report back home findings that could garner bipartisan support for condemnation of South Africa.

SA could lobby other African nations

What are the tools and instruments at the disposal of South Africa and the US in their moves against each other going forward? In advocating a review of relations, the US senators sponsoring the fore-mentioned resolution implicitly suggest potential areas in which a pessimistic US could target South Africa. These are wide-ranging, everything from a demand that South Africa stops dealing with US-sanctioned companies (Chinese and Russian) to exclusion from the African Growth and Opportunity Act. South Africa, with less tools and instruments to leverage, would likely take the pragmatic step of allying itself even more with Russia and China. This is already at play as South Africa refused to participate in military exercises with the US – Cutlass Express – while embracing Mosi II.

South Africa could also try to lobby other African countries to take it’s non-aligned position – which is seen as code for the support of Russia and China – particularly at the United Nations. Pessimistically, however, the US might elect to work directly with other continental powers, thus undercutting South Africa’s pre-eminence on the continent, which is already on shaky ground.

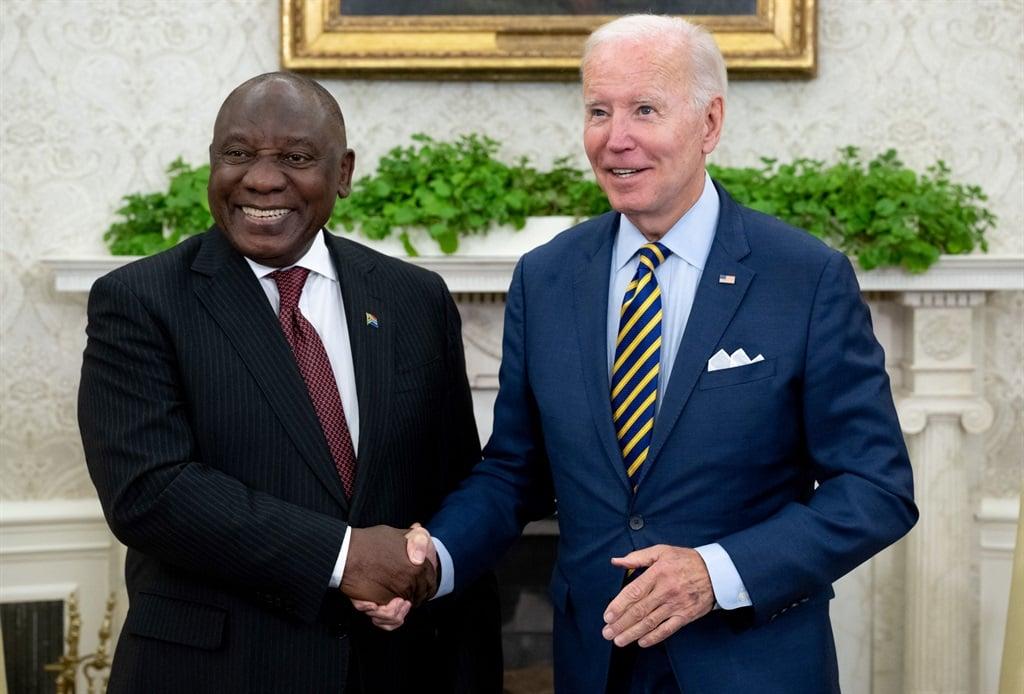

Under the Biden administration, the US has invested a lot in diplomatic engagements with South Africa. Using the notions of re-engagement and reset of relations, an optimistic US must have calculated that investment in diplomacy would persuade South Africa into its corner. President Cyril Ramaphosa was one of the first few African leaders that Biden called after winning the presidency. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken chose Pretoria for the launch of the new U.S. Strategy Toward Africa in Pretoria rather than elsewhere on the continent. High-level engagements have been sustained. But if the Mosi II saga is a measure of effectiveness of US diplomatic investments, the US has not garnered desired returns. It suggests that the new US strategy for Africa is already facing headwinds in Africa on the back of South Africa’s resistance. With South African officials maintaining a pessimistic, even dismissive position towards the US, Washington may elect to invest more in citizen diplomacy, dealing directly with South African populaces, civil society, and businesses. Though pragmatic on the part of the US, such an approach could be interpreted as a form of regime change strategy, further driving the governing African National Congress into its own pragmatic embrace of Russia and China.

It can be said that South African leaders have looked at the current global balance of power and decided to pursue tightrope relations with both the Russia-China axis as well as the US and the West.

The naval drills have caused tensions, but diplomatic relations with the US have not entirely broken down. Two recent events demonstrate a semblance of South Africa’s optimism towards the US First, is the January 2023 visit to South Africa by US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, during which a bilateral meeting was held with South Africa’s Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana and a courtesy call President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Opinions editor Vanessa Banton curates the best opinions and analysis of the week to give you a broader view on daily news happenings.

The second visit is that of US Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee in early February for an US-South Africa university partnership conference at the University of Pretoria. The conference was also attended by the South African Minister at the Department of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor. In both events, sentiments that approach mutual optimistic were expressed.

Combined, South Africa’s optimistic-pessimistic dance with the contending powers amounts to pragmatism. South African geopolitical strategists seem to be saying: we can play both the East and the West and win on both scores. This ambivalent position will be put to severe test if indeed the US decides to shift to a higher level of pessimism in the coming days. Interesting days lie ahead.

– Dr Bob Wekesa is deputy director at the African Centre for the Study of the United States, Wits University and visiting fellow at the University of Southern California’s Center on Communication Leadership and Policy.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press