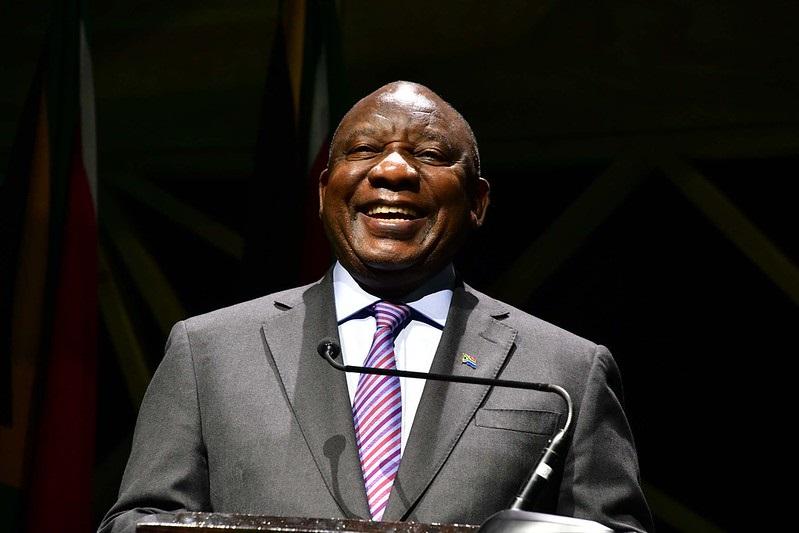

Africa-Press – South-Africa. Following the Constitutional Court’s ruling on Wednesday on the Section 89 report, President Cyril Ramaphosa must now decide whether to institute review proceedings in the lower court with jurisdiction or leave it, writes Selby Makgotho.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Constitutional Court bid to have direct access or exclusive jurisdiction to the court to review and set aside the Section 89 report was rejected on Tuesday. This leaves him with two options: either institute review proceedings in the lower court with jurisdiction or leave it.

If he goes with the first option, the Western Cape High Court is the proper legal forum as it has jurisdiction to adjudicate on the dispute. The jurisdiction in civil proceedings is premised on the basic principles of following the respondents or where the cause of action arose. Parliament is in Cape Town, and it is the one that appointed the Section 89 Panel.

The second option is to leave the report as it does not have any legal force, in its current form. This leaves Parliament with the option to consider what to do with the information as contained in the Section 89 panel report should the President not take any immediate steps to seek legal recourse in the High Court in the wake of the outcome of the Constitutional Court order.

Independent of Parliament

According to the Good Governance Africa journal of December 2022, the Section 89 panel is specifically independent of Parliament. However, the findings are not in themselves final and binding on whether President Ramaphosa should be impeached or not. His fate, rather, depends on what Parliament itself decides to do with the information – a purely legislative decision. This, too, puts him in a difficult position as he would not be able to review the legislative decision in terms of the provisions of the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (PAJA).

On the face of it, the credibility and integrity of the constitution of the panel are without question. Flowing from the EFF v Speaker of the National Assembly 2017 Constitutional Court judgment, the credibility of the panel is without question. In this judgment, Parliament was directed to develop clear rules and guidelines in relation to the impeachment proceedings of a sitting Head of State. The Constitutional Court held in 2017 that the failure by the National Assembly to develop the rules regulating the removal of the President in terms of Section 89 (1) ought to be remedied.

As opposed to the previous parliamentary panel to test the allegations of misuse of state money for personal home-related security upgrades at former President Jacob Zuma’s Nkandla homestead, led by former Police Minister Nathi Nhleko, the rules have since been developed to have a more independent external panel consisting of retired judicial members and Senior Counsel.

It is not quite clear at this stage as to why the President preferred to go directly to the Constitutional Court because direct access exists in the following three circumstances: direct constitutional implication that threatens the (constitutional) stability of the country, arguable point of law, or the interest of justice.

The Constitutional Court was, therefore, not convinced that any of the three circumstances exist in the current application. The Court did not even go to the extent of hearing oral evidence.

Prima facie or sufficient evidence?

On paper, it was found that a proper case for direct access or exclusive jurisdiction has not been made. In the founding affidavit, the President largely dealt with secondary issues.

One of the things that seemed to bother him is whether the Section 89 had considered prima facie or sufficient evidence. It should be borne in mind that sufficient evidence is one of the requirements in the stages set out by Parliament in case impeachment proceedings were to unfold. The question relating to the difference between prima facie and sufficient evidence are reserved for merits. The President, in the affidavit, has taken a stance that the panel has conflated the two (prima facie evidence and sufficient evidence) and that it largely relied on hearsay evidence.

The developments from the Constitutional Court leave the door wide open for the President to approach the Western Cape High Court and start the matter there. Again, it needs to be borne in mind that the Parliament has itself rejected the Panel report, leaving it to the opposition parties represented in Parliament to run with it.

Several other state institutions are still busy with the investigations as mandated in terms of the Executive Ethics Act. The reports of those investigations are yet to be released. It is either the President makes a move to the Western Cape High Court or waits for the outcome of the investigations by other institutions or the National Assembly does.

In terms of the rules of Parliament, the entire process is still at stage one. The motion of confidence was submitted and debated. A decision was taken to institute a Section 89 Panel, which ultimately completed and submitted a report (but rejected). The President came in and sought to challenge the process, which has since been rejected.

The second stage of the process would have been to establish an ad hoc committee for impeachment, which would assess all the evidence and make recommendations, if any, to Parliament. The third and last leg would have been the actual impeachment process with the requirement of a two-thirds majority.

– Selby Makgotho is a legal commentator and a PhD candidate in Public Constitutional and International Law at Unisa.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press