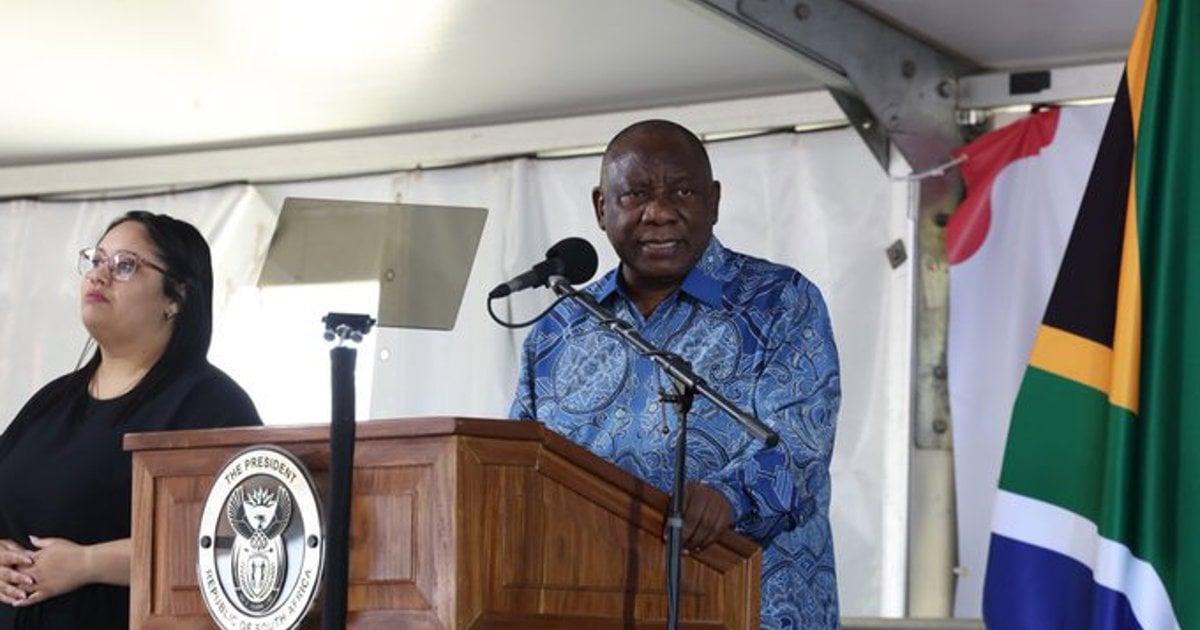

Africa-Press – South-Africa. On 10 June 2025, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced developments on the National Dialogue that he proposed just over a year ago. These developments include the establishment of a team of “eminent persons” whose role will be to “guide and champion” the dialogue.

These “eminent persons” are influential individuals in government (current and former), the private sector, academia and broader civil society (to some extent).

According to the president, the dialogue aims to discuss the challenges facing South Africa and to “forge a path into the future in dialogue with one another”.

Ramaphosa likened this National Dialogue to the discussions that occurred during apartheid.

He stated: “Through dialogue, we were able to deal with the challenges that the apartheid system caused in our country and achieved peace and overcame violence. We established a democracy and ended apartheid. Following the negotiations process, we used dialogue to start building a united nation where once there had only been conflict and division. We achieved all this because we came together in dialogue to discuss our difficulties, our concerns, our hopes and our aspirations as a people”.

On the surface, a National Dialogue seems like a good idea. South Africa is increasingly becoming polarised, with divisions occurring along racial, class, ideological, ethnic and gender lines. There is no question that ours is a deeply divided society, and that dialogue has a place in healing a divided people.

I understood this a few years ago when I attended a march against the ZANU-PF’s authoritarian reign in Zimbabwe, held in Pretoria by the Zimbabwean diaspora.

What was supposed to be a protest against the brutality of the regime exposed deeply concerning divisions that made it clear that the issues in Zimbabwe are deeper than the reality that the ZANU-PF government enjoys a monopoly of violence and governs with a margin of terror.

Scores of protestors held posters calling for cessation, arguing that Matabeleland should break away from the Republic of Zimbabwe, using regressive arguments rooted in ethnic chauvinism. But at the heart of this thinking is the unacknowledged trauma of Gukurahundi, a genocide that ripped through Matabeleland between 1983 and 1987, where tens of thousands of Ndebele people were slaughtered by the Fifth Brigade under the instruction of Robert Mugabe’s government.

The lack of dialogue about Gukurahundi in Zimbabwe has not only made victims of the genocide invisible but has cemented unimaginable generational trauma. There is a necessity for dialogue in Zimbabwe, just as there is in many parts of the continent where traumas have gone unacknowledged. So, as a principle, I do support national dialogues. I value their significance.

But scratch beneath the surface of the proposed National Dialogue in South Africa, and you realise that here, it is nothing more than a distraction from the failure of the democratic government to achieve meaningful transformation. Unlike in Zimbabwe, where injustice has not even been acknowledged, in our country, the issue is not about a lack of dialogue but rather, lack of action.

Furthermore, the president’s likening of the dialogue to negotiations that “ended” apartheid is manipulative and a distortion of history. The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), the negotiating forum established in 1991 after the National Peace Accord, which aimed at transitioning South Africa from apartheid to a democratic government, may have provided a platform for dialogue, but it did not “end” apartheid.

The power of mass action, both domestically and internationally, coupled with the economic and political unsustainability of apartheid, led to its end. By the time the negotiations happened, the apartheid regime was so isolated globally that the economic logic and incentive for apartheid was no longer sustainable.

It was the people of South Africa and our allies across the world who made apartheid unworkable and made negotiations a logical conclusion. Insisting that CODESA “ended” apartheid is a form of erasure of the role that South Africans played in their liberation, and historical revisionism that has come to define the narrative of struggle in the democratic dispensation.

The issues that the president wants to see addressed by the National Dialogue are not unknown. The government is fully aware what the issues in our country are. Its own research institutions such as the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), the Gauteng City Region Observatory (GCRO), government departments, think tanks, learning institutions, the media, and all manner of institutions and platforms have repeatedly communicated what the issues in South Africa are and what they have been since the dawn of democracy.

Ramaphosa and the government know exactly what ails us and what solutions are needed to alleviate the struggles that we confront.

There is nothing that a consultative process will bring to light that protesting communities, activists, scholars and people on the margins (including women, the LGBTQI+ community, migrants, persons with disabilities, Khoisan people, etc) have not already expressed. Even more, the root of the problem for which symptoms have been protested over, analysed and commented on by South Africans across all walks of life, is known.

The government of our country knows that unless the nucleus of racial capitalism, from whence the chromatin network of landlessness, poverty, inequalities, and all forms of structural violence emerges, is addressed, meaningful transformation will not happen. No matter how much ignorance it feigns, the government knows.

For this reason, I am in full agreement with Sinawo Tambo, the spokesperson of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), who posits that Ramaphosa is attempting to make South Africans take collective responsibility for the failures of the party he leads and seeks to mask this scapegoating with the sentimentality of a National Dialogue.

The dialogue gives an illusion of a government that listens when in reality, the South African government, and certainly, the African National Congress (ANC), has proven impervious to listening.

Ramaphosa wants to keep South Africa in an endless cycle of dialogue to distract us from the fact that the government is failing to facilitate the radical reform that is needed to redress the injustices of the country’s amoral past.

He wants us to dialogue because he does not have the guts to make demands on those who remain resistant to change – the unrepentant White minority that has become emboldened by the inertia of his government and has opted out of participating in the process of nation-building without consequence. Instead, the oppressed are expected to beg for justice and to negotiate for humanisation.

Instead of dedicating taxpayers’ resources to a performative consultative process, the government should be channelling those resources towards programmes/initiatives aimed at addressing gender-based violence, structural reform, economic and spatial justice, and service delivery.

These are some key issues that South Africans have already expressed as needing urgent intervention. These are issues the country has already communicated through dialogues in communities, through the media and on platforms.

To want to have South Africans repeat them for the purpose of symbolism is callous. President Ramaphosa must reflect deeply on the sentiments expressed in Karl Marx’s 11th thesis in the Theses on Feuerbach, who, in his critique of the traditional role of philosophy, which he saw as primarily theoretical, contends that: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it”.

In the context of South Africa, the people have dialogued in various ways; the point for the government is to muster the political will to act.

Malaika, a bestselling and award-winning author, is a geographer and researcher at the Institute for Pan African Thought and Conversation. She is a PhD in Geography candidate at the University of Bayreuth in Germany.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press