Africa-Press – South-Africa. The role of the magistrate’s court in curbing gender-based violence in South Africa, considering their proximity to the general public, has become more critical now than ever, writes Thuli Zulu.

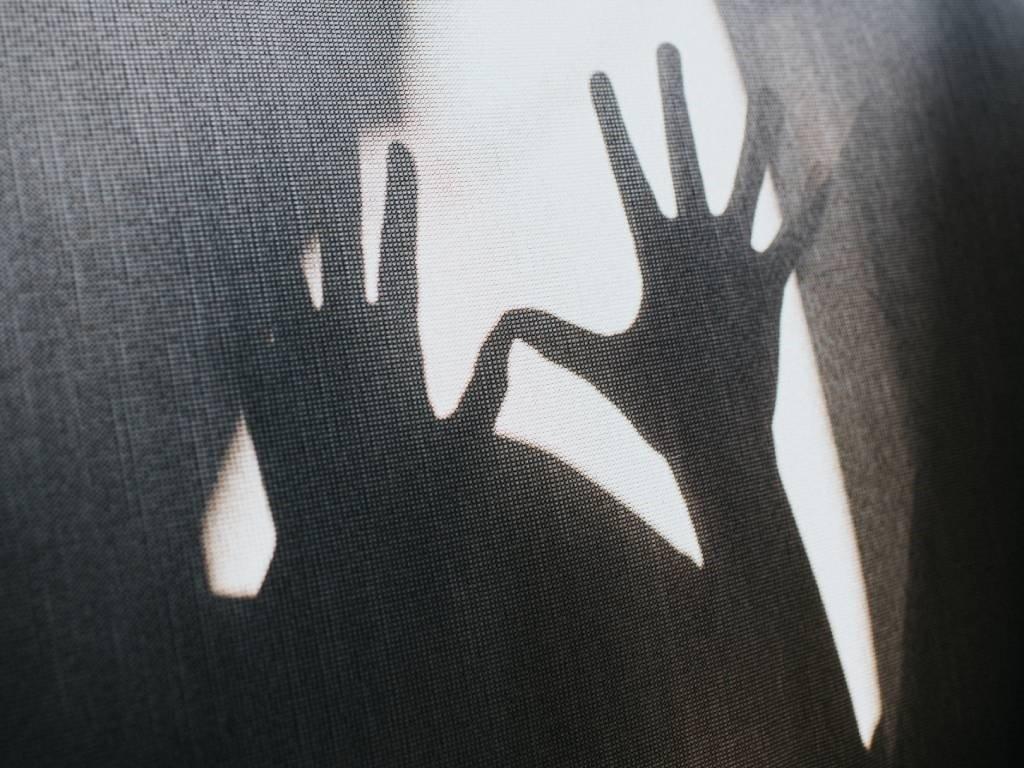

It is women’s month, so we are anticipating reading about women’s rights and what must be done to advance these rights. This is in relation to the scourge of violence that women face daily. If unlucky, we will also find ourselves with prominent hashtags where loved ones are asking for assistance with finding their nieces, sisters, friends, mothers or daughters. This has been a trend in the past years during August when South Africa finds herself celebrating women.

A lot has been said about how to best deal with gender-based violence, including the role courts, can play in dealing with this pandemic.

READ | OPINION: Mashupye Maserumule – Stop casting women and children as vulnerable if we going to stop GBV

Courts are usually characterised by the matters they adjudicate; by their nature, magistrate courts are the first point of entry to the justice system for many people seeking justice. They are also known as “courts of first instance” for many women facing gender-based violence. Women come to these courts to seek protection orders and maintenance orders. They can also lay criminal charges against perpetrators of gender-based violence.

Power imbalance

All courts are open to the general public, and anyone is permitted to sit and listen to proceedings, except in certain exceptional cases closed to the public. Observing the proceedings and the way women must perform for magistrates is saddening. This is because the courts can get theatrical, with magistrates holding power over the proceedings. This power imbalance causes magistrates to be dismissive of witnesses so that witnesses cannot adequately present evidence.

To receive Opinions Weekly, sign up for the newsletter here.In a gender-based violence case against one of Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS) clients who had killed her partner, the magistrate court utterly dismissed the evidence rendered by the witness, questioning the extent of violence exerted on her that would warrant her killing her partner. The extent to which women must go to convince the magistrate that their lives are in danger is dehumanising and discouraging for them to continue seeking justice against GBV. It then makes it difficult to understand how these courts can provide justice for women standing before them if the issues that engulf them continue to exist.

In cases where women stand before these courts to seek justice against their abusive partners, it is expected that these women must perform and show the extreme gravity of abuse they have experienced from their partners. When women plead self-defence where their partners have pressed charges against them, the woman would have to go to great lengths to depict the danger she was facing to defend herself. Showing the extent of danger one met to prove that they acted in self-defence may be law; however, it is absurd that this is the reality for many women with the rising numbers of gender-based violence in South Africa.

Grooming

In most cases, magistrates and prosecutors are heard asking women if conducts like ‘poking’, ‘pushing’, or shoving were so life-threatening that the woman had to react with an act of violence. In other instances, when women choose to remain in the same homes as their perpetrators, they are questioned as though they were lying about the danger they were facing, not taking into account that some women were groomed by these men and had nowhere else to go.

This sort of questioning is not just dangerous for the woman taking the stand, waiting for her fate against the abusive man she was defending herself against, but is also very discouraging for women who are sitting in the gallery observing proceedings and contemplating the acts of violence that have been done to them.

READ | OPINION: Irene Charnley- Into what barbaric abyss are we descending? GBV horrors beg this question

You hear mummers, disagreements and gasps as the prosecutor and the magistrates question the danger women had perceived in reacting violently against their partners. These reactions are often warranted because they insinuate that these women were not in danger, considering that they are still alive and got away safely. This is, of course, against them in a coffin, protests from organisations against gender-based violence, and endless press statements from different actors in the government, as we saw with the total shutdown march in 2018.

Toxic forms of masculinity

The role of the magistrate’s court in curbing gender-based violence in South Africa, considering their proximity to the general public, has become more critical now than ever. This is in line with the rising number of reported cases of gender-based violence and the continuing toxic forms of masculinity men grapple with.

According to the South African police service, the 2021/2022 third quarter’s crime statistics revealed that 903 women were murdered, and 11 315 rapes occurred between October and December 2021.

In their line of questioning, magistrates must also rid themselves of the misogynistic understanding of intimacy and violence against women. For magistrates to be better equipped in their jobs, they ought to be sensitised to the realities women face in their intimate relationships.

Want to respond to the columnist?Send your letter or article to [email protected] with your name and town or province. You are welcome to also send a profile picture. We encourage a diversity of voices and views in our readers’ submissions and reserve the right not to publish any and all submissions received.In this current climate, women cannot be asked why they go back to their perpetrators if they are in danger and fear for their lives. Further, the magistrates cannot continue to separate the law from societal conditioning that sees the continuing rise of GBV.

In sensitising magistrates on the societal problems that continue to face women and understanding that law cannot operate outside these realities, we are moving towards a justice system that would see better successes in adjudicating against gender-based violence.

– Thuli Zulu is an advocacy and research officer at the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at Wits University.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press