Africa-Press – South-Sudan. The story of the struggle of the South Sudanese has been told in many different versions, some tragic and some hopeful. The story of my family’s escaping 1984 from The Republic of Sudan to the United States when I was three years old is worthy of a Hollywood script.

My father is a career politician; he held different positions in the Sudanese government. In 1983 the Islamic government decreed the Islamic law as the law of the country. My father and many other South Sudanese politicians rejected the law because Sudan has diverse religious and ethnic communities, and he believed that Islamic law was not best for the country. When he refused to renounce his Christian beliefs and follow Sharia law, he went to prison. Of course, that didn’t stop him. After close to a year behind bars, he got release and gained an opportunity with United State Agency for Development to enter the Ph.D. program at Indiana University. The first Sudan civil war, (1955-1972), had sent my father into exile as a young man, and he found himself at Syracuse University where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

There was one significant barrier to my family’s hope of a safe exit; the Sudanese government gave my father permission to leave the country, but the rest of us – me, my three siblings, and my nine-month-pregnant mother, would have to stay in the Sudan. The authorities made it clear that my father would stay under their thumb.

Determined, my parents hatched a plan that could have gone wrong a dozen different ways. My mother’s brother was a medical doctor in London, so they created documents to convince the Sudanese officials that my mother had a very serious health condition that would threaten the life of her and the unborn baby. They somehow secured permission for all of us to travel to London for her to “seek treatment.” My youngest brother Bil was born there, and then we emigrated to the U.S., where we found ourselves in Bloomington, Indiana of all places. Bloomington, Indiana became a second home for the Duany family, and with our height we found ourselves standing out amongst our age groups and excelling on the basketball court. The community of Bloomington welcomed us, and my siblings and I began to thrive in school and church, which was the foundation for our social and spiritual growth.

Despite the drama of our exodus, I remember my early years for the stability of my home, the love of my parents, and the deep faith that they modeled to us. In the first picture of my family on U.S. soil, we’re all posed in front of the same Bloomington church where I was a member for many years. Church involvement was never an option for us, and neither was the call to love and serve others because of the ways God had provided for us.

As soon as my father was safe in Indiana, he started advocating for peace and striving to help young people to get their education. He also worked to bring other Sudanese young people over to America for school, since he recognized that the opportunity to study at a major American university had literally saved his life. He wanted to do whatever he could to enable others to broaden their horizons in the same way. I don’t remember a time when helping others wasn’t a key part of our family’s DNA—and it’s a legacy that I have worked to continue.

In 2005, the Sudan government signed a peace agreement with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) a rebel movement that was fighting the Government. My father went back to help the country implement peace. As a family we went to visit in 2006 and saw the work my father and mother were doing. That trip was an eye-opening experience for my siblings and me. We saw firsthand how so many young people did not have the opportunities our parents had given us.

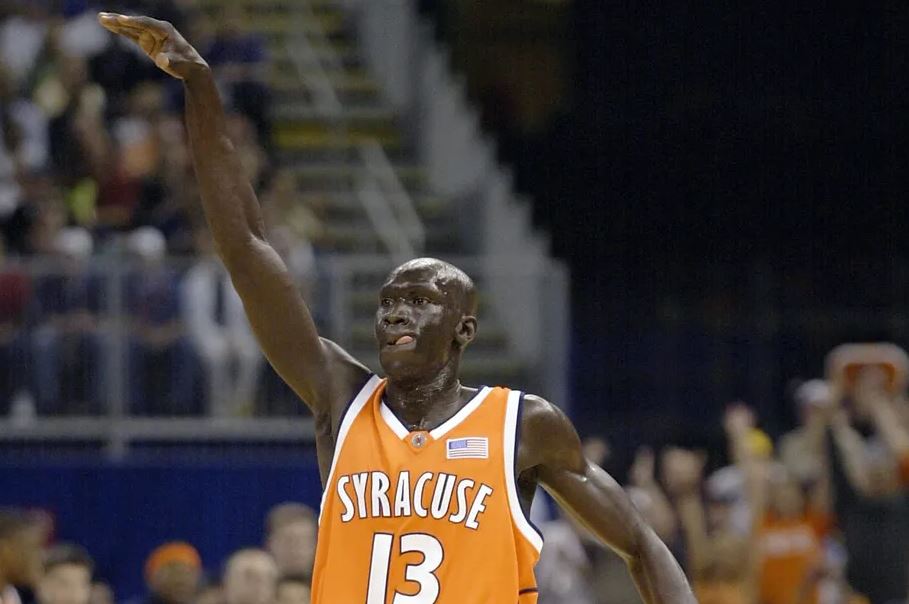

My own efforts to pay it forward and help African young people find life-changing opportunities have centered on basketball. After all, basketball was the key that unlocked so many doors for me–through winning a State Championship in Indiana, as the only senior on the 2003 Syracuse national championship team and in stints overseas. We were a basketball family; all four of my siblings, incredibly, also played Division I hoops. And when I traveled to the South Sudan in 2007 with my brothers Duany and Bil, I looked around and realized that there were plenty of young people there who just needed an opportunity to learn the game.

I’m 6-foot-6, my older brother is 6-foot-4 and my younger brother is 6-foot-8. That typically shocks people in America, but in the now independent South Sudan we didn’t stand out at all. As we walked around, we saw a bunch of guys on their way to work and school, and they just towered above us. Clearly there were many promising basketball players in our midst, but they lacked opportunities to capitalize on that potential. So for about six years, until the civil war in the South Sudan made it too difficult, we enabled dozens of South Sudanese youth to come play basketball at high schools and college in the U.S.

The South Sudanese athletes who discovered new opportunities through our efforts included 7-foot-2 David Nyarsuk (Cincinnati), 7-foot-2 Chier Ajou (Northwestern/Seton Hall), 7-foot-1 Obij Aget (New Mexico) and 6-foot-11 Koch Bar (Bradley). And that’s just a representative sample. Every one of these young men rose to the occasion, succeeding athletically and academically. Eventually, the upheaval in South Sudan sent my family and I to Kenya, where the work we started in South Sudan continues.

Even though my career in international business is demanding, I have served as an assistant coach for a team in Nairobi that brought together young talent from both poor and advantaged backgrounds, and most recently my friend Erik Hersman and I have developed a new organization that will foster more basketball and educational opportunities throughout Africa, with the ultimate hope of supporting a Kenyan team in the planned NBA-sponsored African league.

My parents showed incredible courage and faith when I was a child, leading us to safety in the U.S. and then raising us with Christ at the center of our lives. In my work and family and in my efforts in Kenya and more broadly the rest of Africa, I hope to give my two daughters their own legacy to sustain into yet another generation.