Africa-Press – Uganda. The sixth edition of the Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies Conference staged at Makerere University at the backend of last month struck gold in dedicating its first keynote to Okot p’Bitek.

Prof Charles N Okumu used a delicate and sophisticated, but also simple and direct style to work his way through the keynote titled ‘The Life and Times of Okot p’Bitek.’ Airily direct at times, he told his audience that the bitter froth and women were p’Bitek’s Achilles heel.

The latter submission, Prof Okumu added, materialised because p’Bitek’s wife, Caroline, was not part of the people in the Yusuf Lule Central Teaching Facility’s auditorium in whom he found an attentive audience.

The Ugandan poet was a magnet for women, said Prof Okumu, because he was a good-looking man. By this time the attentive audience had already learnt that p’Bitek “was not born” but rather “kicked himself out of his mother’s womb.” This was, Prof Okumu further revealed, “in the kitchen of one of the missionaries.”

The product of a very subtle alchemy, p’Bitek picked his storytelling skills from his father and his knack for giving sound performances from his mother, who was a traditional singer and dancer. Per Prof Okumu, p’Bitek not only managed to finesse a continuing desire but also excel at mathematics by eating cane, almost incessantly, out of his father’s plantation. Not even warnings that the plantation had an overwhelming number of snakes would stop this only child of Jebedayo Opi and Lacwaa Cerina.

Rejected while at King’s College Budo by an Acholi girl (Rebecca Abitimo) born into aristocracy because he was a mukopi or commoner, p’Bitek “composed an opera and, in the song, he says, poverty is not permanent.” Prof Okumu proceeded to reveal that John Nagenda spruced up the song. Acan, the opera, dripped with influences of Mozart’s The Magic Flute and would go on to be acclaimed as a considerable success after a performance at the Anglican Namirembe Cathedral.

“He extended the theme of rejected love to a full novel,” Prof Okumu said of p’Bitek’s winning performance, adding, “If you have not heard of the book Song of Lawino, then you have not read literature.”

Like father…

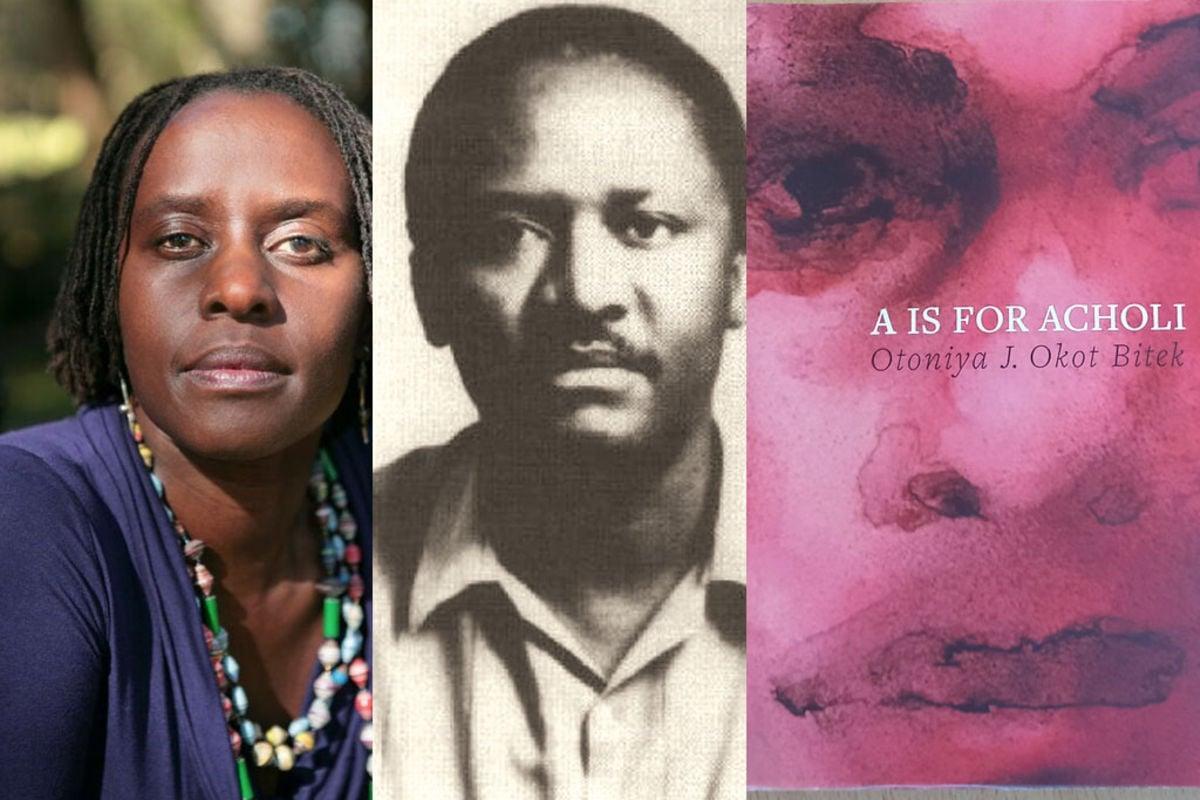

Juliane Otoniya Okot Bitek, one of p’Bitek’s daughters, has over the years made a fit of walking in her father’s illustrious footsteps. Some of her most highly regarded bodies of work speak to the migrant experience. Like her father, she also needs little invitation to shine the spotlight on the ideals of the Acholi people.

The diasporic writer and academic’s latest work, A Is for Acholi, has been shortlisted for the 2023 Pat Lowther Memorial Award. It is a finalist for both the 2023 Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize and the 2023 Jim Deva Prize for Writing that Provokes.

The beauty with Otoniya’s new poetry collection is her ability to employ abstraction as well as dismantle language and form by the repetition of words, punctuation marks and footnotes.

In the 101-page collection that was published by Wolsak and Wynn in 2022, Otoniya tackles the challenges of race, identity, existence, and belonging faced by Africans living in the Black diaspora.

Each letter in the alphabet in the longest poem “An Acholi alphabet” defines the Acholi and their skin complexion, their houses smeared with cow dung, the Acholi dance, the dead poets and singers, the glory and rhythm of ostrich features, the dance of the evil, the small heaps of mangos and homemade brew for sale on the roadside, and the rejection of the Acholi in foreign lands, among others.

Otoniya describes poems like And, Ah, well, and How she talked as “erasure poetry.” She adds: “This is the same suite of poems that I wrote in response to Heart of Darkness.” This is in reference to Joseph Conrad’s novel.

“Working from the same page from that novel, first I erased everything from the page except the word ‘and.’ For the other two poems, I retained all the punctuation marks from that page, but took out most of the words except for a phrase, or two, that I wanted to retain,” Otoniya says.

Adding: “By answering these questions, it almost feels like I’m revealing the tools of the trade, but really it makes me excited to discuss poetry as a creative practice and the page as a space for so much more possibility than a landing page for words. Thank you for reading A is for Acholi.”

Culture, identity

The poem with the longest title, Dark human shapes could be made out in the distance, flitting indistinctly, has four dark human shapes of different shapes. It at one point dwells upon “an air of brooding over an inscrutable purpose/I don’t understand…”

Otoniya says she doesn’t “believe the poet/artist is in charge of how the poems/images are to be interpreted.” Her construal of human shapes “is meant to elicit something, a question, a reaction as you have, but you, the reader, the one to work the meaning for yourself.”

She adds, “I can speak to my process, which was that I was responding to the work of Joseph Conrad, specifically his portrayal of an African woman in his Heart of Darkness that has no name, no real voice and is limited to the archetype of the angry black woman who is limited to her physical beauty.”

The angry black woman is stripped of her voice and soon becomes the object of rage, with the narrator wishing “he could have shot her.” This prompted Otoniya to wonder “why anyone would shoot someone in their own homeland”.

“Yes, of course, he’s illustrating the mindset of a coloniser, but Conrad, the writer, does not offer us any chance to hear her speak. I’ve been thinking about the work of colonialism, through literature like Conrad’s and my responsibility as a poet and academic to think and write against it,” she offers, adding, “Those images are a “play” on the page. A blotting out, with images that look like ink stains (or human shapes referred to on Conrad’s page), to inject a sense of agency in reclaiming agency through artistic representation, or re-‘writing’ a page through erasure poetry that only lets select words through that make the point the poet wants to make.”

Experimentation

Otoniya also talks about “experiment[ing] with the page” in the poem Apparition of a woman.

“I’m also writing in a tradition of poets who use images in their work,” she reveals, adding, “This tradition includes our father, the poet Okot p’Bitek, who collaborated with artists to include images in his poetry. You can see this in older editions of Song of Lawino, for example.”

The poem Ash extols the inventiveness of the Acholi seen in their ability to make salt from ash. It also shines a spotlight on how they suffered under the slave trade, “having been locked to land and free to home we discover ways to salt from ash/also salt licks also salt panning what did we need to sea for/never bound by the ocean until the slavers came down the Nile and marked us…”

The poem ‘There’s something about…Vancouver’ extolls the power of modern education and how it can emancipate women.

“These poems came from a much longer suite of poems that I titled ‘Something about poems.’ The obvious link is in the repetition of the phrase ‘there’s something about’, but the poems bring together the narrative and lyrical traditions of poetry to make a social commentary of the times we live in,” Otoniya says.

Adding: “The themes that each poem deals with are distinct to each poem, but they’re related through form and the fact that they originate from a particular suite of poems. The rest of those poems did not make it into A is for Acholi.”

Poisonous colonial literature

The poem Three letters at a time is sure to give the reader a headache because of its jumbled structure.

“The goal was to make it ineligible and, therefore, to reduce to nothing, to nonsense, the powerful poison of colonial literature, which portrayed us as less than human,” Otoniya says.

For the poem If/once we were, Otoniya says she wanted to use the page as a place where she could bring together form and content to create meaning.

“It isn’t possible to live in the Black diaspora without the love and support of family, friends and community who remind me that Acholi is an expansive way of being in the world. All these people, more, have held me in sustained friendship and family relation and I’m grateful to them. A Is for Acholi is for all of us who struggle with place, time and identity,” Otoniya writes in the Acknowledgements.

According to Wolsak and Wynn, A Is for Acholi is a sweeping collection exploring diaspora, the marginalisation of the Acholi people, the dusty streets of Nairobi and the cold grey of Vancouver. Playfully upending English and scholarly notation, Otoniya rearranges the alphabet, hides poems in footnotes and slips stories into superscripts.

“The poet opens up ways of rethinking history as she rewrites both the 1862 contact of the Acholi people with the British and the racist texts of Joseph Conrad, while also searching for a way to live on lands that are fraught with the legacies of colonisation, similar to her ancestral homeland,” the publishers add.

OTONIYA AT A GLANCE

Juliane Otoniya Okot Bitek holds a Master’s Degree in English and aBachelor of Fine Arts in Creative Writing and a PhD in Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of British Columbia in Canada. She is an assistant professor at Queen’s University, Kingston in Canada. Her other collections of poetry are: 100 Days (University of Alberta Press 2016), and Song & Dread (Talonbooks 2023).

ABOUT OKOT P’BITEK

The product of a very subtle alchemy, p’Bitek picked his storytelling skills from his father and his knack for giving sound performances from his mother, who was a traditional singer and dancer. Per Prof Okumu, p’Bitek not only managed to finesse a continuing desire but also excel at mathematics by eating cane, almost incessantly, out of his father’s plantation

For More News And Analysis About Uganda Follow Africa-Press