By zambianobserver

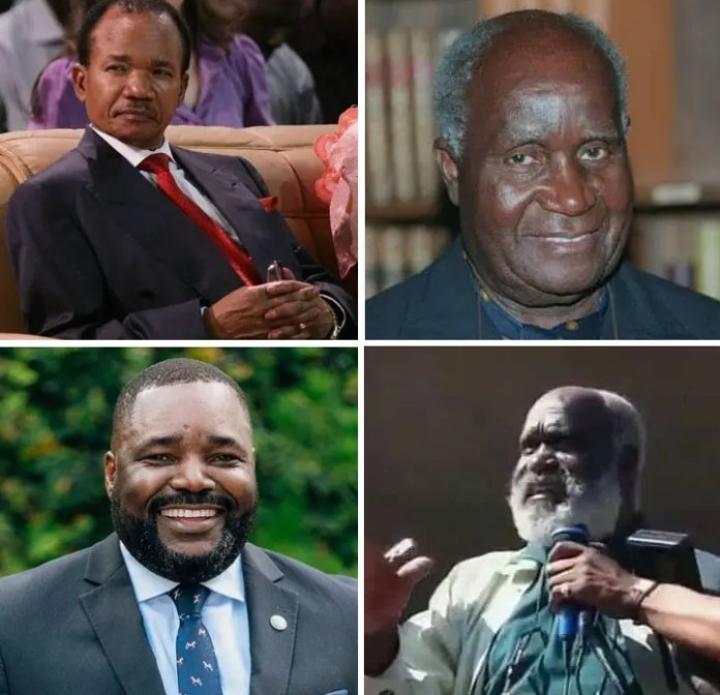

Africa-Press – Zambia. When Zambia transitioned from Kenneth Kaunda’s 27-year rule to Frederick Chiluba’s new multiparty era, the change appeared peaceful on the surface.

However, beneath the handshake diplomacy, one of Southern Africa’s most psychologically brutal political confrontations was unfolding.

On Christmas Day, 1997, Kaunda was arrested, a moment chosen for maximum symbolic impact.

Christmas, traditionally a day of presidential addresses and national unity, became the backdrop for Kaunda being bundled into a vehicle by armed officers.

The timing led many senior diplomats to conclude that the arrest was meant to break Kaunda psychologically, rather than simply pursue legal action.

The government accused Kaunda of involvement in a failed coup in October 1997, led by junior soldiers.

Yet Zambian intelligence insiders later admitted that there was no concrete evidence linking Kaunda to the mutiny.

Kaunda had been out of power for six years, had no military command, and was leading a peaceful political movement under UNIP.

Despite this, he became the central figure blamed for a coup he did not participate in.

At the time, Kaunda was experiencing an unexpected political resurgence, drawing large crowds to his rallies and maintaining widespread respect across rural districts.

Inside State House, Chiluba’s camp feared that Kaunda could potentially win the 1998 elections if allowed to run.

Kaunda’s moral authority still overshadowed other political figures and remained a unifying force across tribal lines, unlike the fragmented new elite.

For many observers, his arrest was interpreted as a pre-emptive political strike rather than a measure of national security.

During the same period, Kaunda was shot in the neck by government forces while leading a peaceful protest.

This injury left him physically vulnerable at the time of his detention.

For many Zambians, this act reinforced the perception that the state was willing to use lethal force against a national symbol.

Kaunda was subsequently held in Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, a facility typically reserved for murderers, armed robbers, and political radicals.

This was not merely imprisonment but an attempt to erode his legacy by equating him with dangerous criminals.

Some prison officials later revealed they were instructed to treat Kaunda “as an ordinary dangerous suspect,” delivering a psychological blow aimed at undermining his stature.

The international community, including the Commonwealth, the United Nations, and African heads of state, intervened behind the scenes to pressure Chiluba to release Kaunda.

Even Nelson Mandela reportedly sent private messages condemning the treatment of the former president.

Diplomats feared that Zambia was descending into personal vendetta politics, with the potential to trigger ethnic tensions or civil unrest.

Chiluba’s own cabinet was divided on the matter, with some ministers warning that humiliating Kaunda could backfire politically.

Nevertheless, hardline security advisors convinced Chiluba that neutralising Kaunda was essential to consolidating power.

Ironically, the detention had the opposite effect of what Chiluba intended.

Kaunda emerged from prison more respected, seen as a statesman, and admired internationally as a martyr of democratic abuse.

The attempted political witch hunt, while meant to cripple Kaunda’s comeback, ultimately strengthened his legacy.

Historians agree that there was no direct evidence linking Kaunda to the coup, the arrest’s timing and style were deeply political, and Chiluba had strong incentives to remove a key rival.

Official statements cited national security, but the methods, symbolism, and sequence of events pointed clearly to a targeted political campaign.

The detention of Kaunda remains a powerful reminder of how political power struggles can shape the destiny of nations and the enduring respect commanded by principled leadership.

Shipungu writes:

PRESIDENT KAUNDA GETS A TASTE OF HIS OWN MEDICINE-former president KK was arrested on Christmas Day in 1997 and held under emergency powers invested in FTJ; after the coup attempt.

Post independence, KK strategically banned a number of political parties from challenging his leadership. To consolidate his power, in 1972 he called for a constitutional amendment; abolishing the multiparty political system, establishing a one-party state.

Nonetheless, after the reintroduction of the multiparty political system in 1991, KK lost elections to Frederick Chiluba (FTJ), who became Zambia’s second president.

Aside from that, in the November 1996 elections, FTJ was re-elected, and his party won 131 of 150 seats in the National Assembly. Poetic justice is real, constitutional amendments enacted in May 1996 disqualified KK from participating in any future elections ( Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, January 30, 1998).

This is were the story hits the climax though.

Four days after Zambia celebrated it’s 33 years of independence, the country woke up on the morning of 28 October 1997 to hear what many later described as a slurred, drunken-sounding voice announcing the overthrow of the Government of Zambia over the

national radio station (ZNBC).

Identifying himself as “Captain Solo”, Captain Steven Lungu claimed to speak on behalf of a “national redemption council” whose intention was “saving our nation from total collapse”.

In his radio broadcasts that began shortly after 6 a.m, Captain Solo declared the constitution suspended, political activity banned, and all airports closed. Demanding that President Frederick Chiluba surrender by 9 a.m, he claimed to have troops surrounding State House and criticised the government for corruption and criminal activities.

The coup attempt, described by Captain Steven Lungu as “Operation Born Again”, saw a group of soldiers drive armoured cars to capture the radio station, while another band of soldiers at the Arakan army barracks in Lusaka planned to take hostage Zambian army commander Lieutenant General Nobby Simbeye. That second group, allegedly led by Captain Jackson Chiti, failed to find the commander and instead took hostage his family members and other officers, later breaking into a private bar and looting a refrigerator full of beer.

The escaped lieutenant general raised an alarm, rousing troops loyal to the government.

Contrary to Captain Solo’s increasingly jittery broadcast statements, there were no rebel troops surrounding State House. By 8 a.m, there was silence on the airwaves. Some of the mutinous soldiers at the radio station stripped off their army fatigues and ran away. Others barricaded themselves in the radio station’s offices. A few tried to resist a commando unit, wearing red berets, but were quickly overwhelmed.

A reported total of 15 were immediately arrested, and at least one of the rebel soldiers was fatally shot in the fighting as the troops loyal to FTJ regained control of the radio station.

By 8:36 a.m, a lieutenant colonel announced to the nation over the radio that the government was in control and that all culprits would be arrested. ZNBC TV crew later filmed and broadcast the image of Captain Solo lying on the ground as soldiers stamped on his chest.

Actually, it had taken about three hours to suppress the poorly organized, bumbling coup attempt. The Zambian security forces began a sweep of those who had fled, nabbing four soldiers who drove off in Lt. Gen. Nobby Simbeye’s car. Two others were soon discovered near the radio station after school children spotted them in their hiding place (The Post (Zambia), 29 October 1997/Amnesty International – 2 March 1998).

After the coup attempt, marches and rallies supporting the government were staged across the country. The opposition political parties like, UNIP, the Liberal Progressive Front (LPF) party, and the Zambia Democratic Congress (ZDC) party, condemned the coup attempt. Religious groups and human rights organizations like LAZ, AFRONET, FODEP and others decried the coup attempt (Times of Zambia (Zambia), 30 October 1997/Reuters, wire service report, 26 December 1997)

This coup attempt led to a special cabinet meeting on the following day, on 29 October, 1997. The cabinet reportedly discussed how best to handle the investigation of the coup attempt. Later, on the very day; President Chiluba declared a state of emergency (Times of Zambia (Zambia), 30 October 1997).

According to the publication by Amnesty International on 2 March, 1998; Captain Solo, never mentioned KK, nor other opposition politicians in his address.

Equally, the Government never suspected the opposition to have been involved in the coup attempt.

“The government is not suspicious that the opposition was behind the attempted coup,” presidential spokesman Richard Sakala told reporters at a 29th October news briefing that was held while President Chiluba met with his cabinet (Agence France Presse, wire service report, 29 October 1997).

Though, on October 27, 1997; the day before the coup attempt, The Post newspaper had printed an article by journalist Dickson Jere that quoted KK warning of “an explosion soon” unless there was genuine dialogue between the ruling Movement for a Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) and opposition parties.

“Something big will come and of course MMD will blame UNIP for that,” warned KK, who was interviewed by telephone in South Africa. He added: “But it won’t be UNIP. It will be the people of Zambia who are going to act.”

Asked by Dickson Jere when and how a possible political insurrection would occur, Kaunda said he didn’tknow, but “…I just know that it will involve the people. (Reuters, wire service report, 26 December 1997).”

Because of this interview with KK, journalist Dickson Jere (currently, a prominent Zambian lawyer) was detained.

In fact, after declaring the state of emergency, many were arrested.

At the rally, MMD National Chairman Sikota Wina said that the “big fish” in the coup attempt were still in hiding. President Chiluba agreed that there were many people who could have been

involved. “They usually use fools to stage this sort of thing,” the President said. “So far, a lot of information has come through from those arrested. They have started telling the truth. I am

enjoying this situation because everything is unfolding.” He added.

KK’s statement in The Post newspaper later became central in justifying his arrest without charge on 25 December 1997. More than 100 heavily armed police, some of them in a troop carrier, surrounded his house just three days after he returned to Zambia from two months’travel to the United States, India and the United Kingdom (Reuters, wire service report, 27 December 1997).

Kenneth Kaunda appeared on 29 December in court closely guarded by almost 20 police officers. Afterwards, a police helicopter whisked Kenneth Kaunda off to Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison in Kabwe, about 120 kilometres to the north, without informing his lawyers. Kenneth Kaunda began a hunger strike that ended five days later, after former Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere intervened, visiting him in prison and persuading him to eat.

On 31 December 1997, President Chiluba ordered the then 73-year-old opposition leader transferred to house arrest as a “restricted person”, under Section 3.3(a) of the Preservation of Public Security Act and Regulations 16(1) of the Preservation of Public Security Regulations (Statutory Instrument No. 151 of 1997, Supplement to Government Gazette, 31 December 1997).

These Regulations also banned Kenneth Kaunda from political activity, prohibited him giving interviews to the press, and restricted his access to visitors. Armed paramilitary policemen set up camp around his house, putting up barbed wire and disconnecting telephone lines to the house. Initially, his lawyers were prevented from seeing him, contrary to the provisions of Article 26(1)(d) of the Constitution.

UNIP National Chairman, retired general Malimba Masheke was also barred. Four UNIP activists also claimed security force officers prevented them from visiting Kenneth Kaunda on 24 February 1998. Frank Musonda, Barry Mwape, Danny Zimba and Dr. Kaunda’s photographer, Sunday Musonda, allege that police told them they would not be allowed to see their political party leader (Times of Zambia (Zambia), 27 February 1998).

It’s very important to always remember that when you are a president, you become an inspiration to those aspiring to hold the office you’re holding. So, when you are in the office, make sure you set the right inspiration. While in office, you can choose how you would want to be treated after you leave that office. Never ignore being fair to your opponents’ and making peace with the present for a peaceful future: because, even people you don’t like can become presidents ❤

Copyright ©️ Shipungu 2025

Source: The Zambian Observer

For More News And Analysis About Zambia Follow Africa-Press