By Lawrence Makamanzi

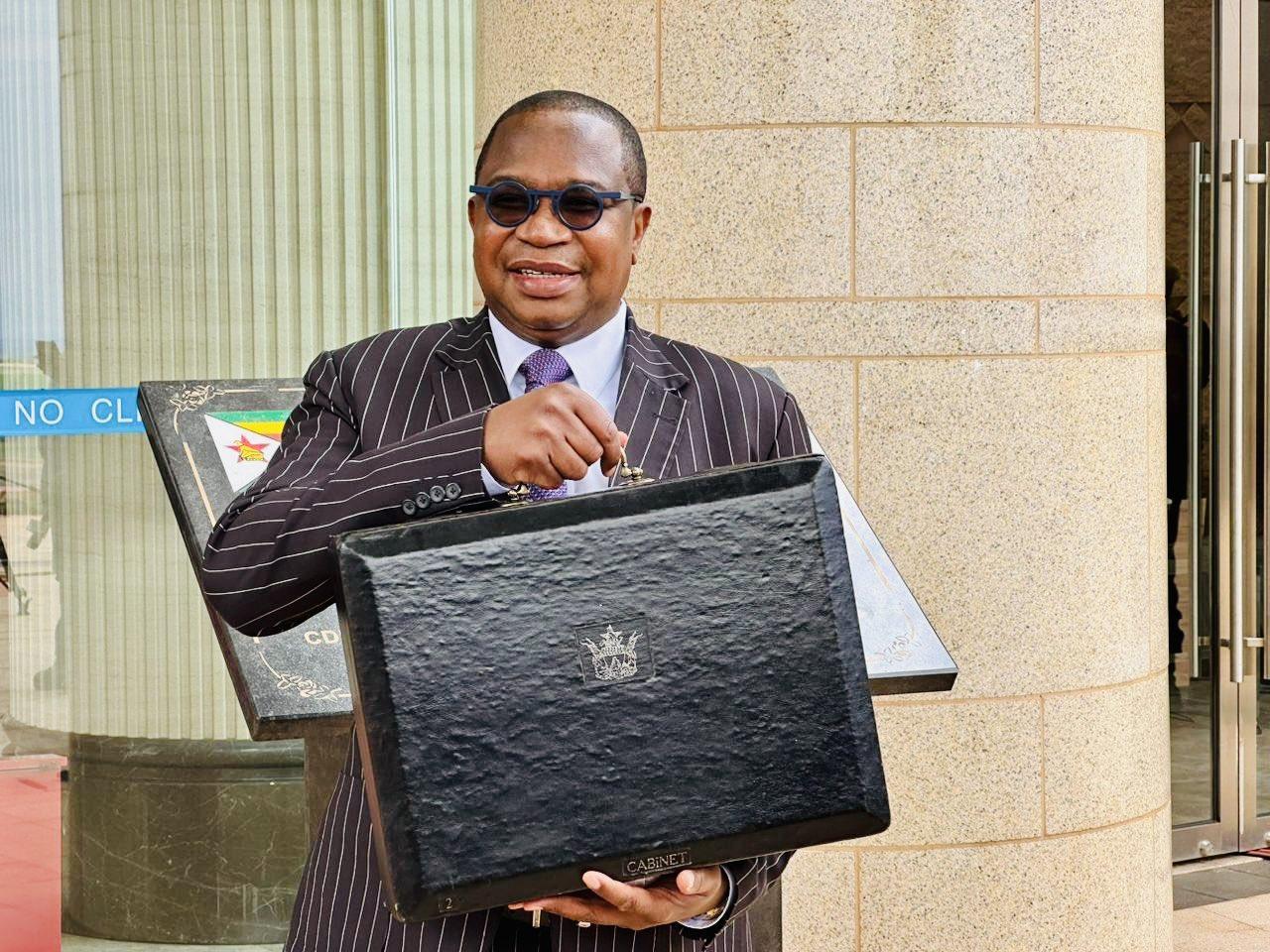

Africa-Press – Zimbabwe. When Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube rose to present Zimbabwe’s 2026 National Budget under the lofty theme “Enhancing Drivers of Economic Growth and Transformation Towards Vision 2030,” few would have expected a fiscal plan that so clearly exposes the contradictions between stability and survival, prudence and poverty, growth and exclusion.

On paper, this ZWG312.6 billion budget looks methodical—anchored in macroeconomic discipline, consistent with National Development Strategy 2, and outwardly pro-growth. Yet beneath its calm technocratic tone lies a troubling void: a failure to confront the country’s deepening human crisis in ways that are bold, redistributive, and people-centred.

The Minister’s own words acknowledge progress. “The year 2025 marks the end of the NDS1 implementation period with indications that most of the NDS1 targets were achieved,” he declared, celebrating the “introduction of the local currency (ZiG) in April 2024, which has restored price and macroeconomic stability.” Stability, however, is not the same as sustainability. The restored balance sheets in Treasury offices have not translated into balanced plates in ordinary homes. For the majority of Zimbabweans, stability has meant little more than surviving the same harshness in ever-harder currency.

The headline figure of ZWG312.6 billion was touted as testimony to fiscal realism, yet it masks an underfunded social state stripped to the bone. Spending requests from ministries and departments had totaled ZWG825 billion—meaning Treasury has cut 62% of all bids. In the minister’s own numbers, the message is brutally clear: the government has chosen containment over compassion. It is a budget that protects solvency rather than the social fabric.

A glance at the allocations shows that the state continues to fatten the muscles of administration and security rather than the heart of welfare. The Defence Ministry receives ZWG19 billion, Home Affairs ZWG17.2 billion, and the Office of the President and Cabinet ZWG11 billion. Combined, these outlays almost match the entire social protection expenditure directed to millions of struggling families through the Social Welfare Ministry, which has been allocated a paltry ZWG12.6 billion. Education and health, the cornerstones of human development, jointly receive less than ZWG80 billion—ZWG30.4 billion to Health and ZWG47.3 billion to Education—more than half of which will be consumed by employment costs. There will be little left for textbooks, classrooms, clinics, or medical drugs.

This neglect unfolds in a country where, according to the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, over two million youths are not in employment, education, or training, while 50,000 children dropped out of school in 2024 alone due to poverty. Teachers continue to flee the profession—between 5,000 and 15,000 have left since 2023—and the healthcare system is bleeding personnel and patients equally. Minister Ncube’s figures may be tidy, but they are too sanitized to capture the noise of hungry classrooms or the silence of drug-ravaged streets.

His revenue measures, likewise, are framed as rational fiscal tools but reveal a widening disconnect between economic calculus and lived reality. The much-publicized tweaks to the Intermediated Money Transfer Tax (IMTT) and Value Added Tax (VAT) are a succinct example. Ncube has reduced IMTT on local ZiG transactions from 2% to 1.5%, maintaining the 2% tax on foreign currency transactions, while increasing VAT from 15% to 15.5%. The rhetorical framing suggests relief. Yet, as analyst Tendai Ruben Mbofana bluntly wrote, this is “not an act of listening, but a calculated sleight of hand.” The truth, as he notes, is that most transactions in Zimbabwe are in USD, not ZiG. The so-called reduction is cosmetic; the simultaneous VAT hike neutralizes any savings and extends the burden to everyone, including the poorest who buy bread, pay for airtime, or struggle to send a child to school.

The introduction of a new Digital Services Withholding Tax—targeting payments to offshore platforms for services such as e-hailing and online content—might align with global tax practices, but its domestic impact could be inflationary and anti-innovation in an economy trying to grow digital competitiveness. In a country desperately needing youth-driven tech entrepreneurship, such taxation looks less like revenue diversification and more like digital suffocation.

Economist Godfrey Kanyenze warns that the test of any national budget “is best measured by its gravity in addressing welfare-based issues,” and that recent budgets have instead “become a ritual to justify tax increases while turning a blind eye on people-centred commitments like the Abuja Declaration on Health.” This year’s fiscal plan fits his critique perfectly. Donor support is expected to decline by US$300 million, yet Treasury’s answer is to widen domestic taxation rather than restructure priorities. In short, the state continues to extract from the poor what it is failing to secure from global partners or its own informal economy.

To Ncube’s credit, the budget does retain a disciplined fiscal framework. Deficits remain modest (projected at -0.3% of GDP), debt at 44.7% of GDP, and nominal growth at 5%. Diaspora remittances are projected above US$2.8 billion, and exports are expected to exceed imports marginally. But such aggregates speak more to macroeconomic scholarship than to the morality of governance. Fiscal restraint divorced from social renewal is technocracy without humanity.

The allocations set aside for innovation hubs, education infrastructure, and development projects—ranging from the University of Zimbabwe’s new Quinary Hospital to the Lupane Technovation Centre—signal a desire to invest in knowledge and production. There are also references to infrastructure achievements like the ongoing Harare–Beitbridge highway, Gwayi-Shangani Dam, and vocational training centres. These are tangible positives that strengthen productive capacity and public confidence. Yet they are offset by a glaring absence: an actionable vision for job creation, drug abuse mitigation, or urban poverty alleviation. The macroeconomic tables in the budget do not translate into a moral framework that places citizens above statistics.

Zimbabwe’s most corrosive crises—rising inequality, joblessness, and social exclusion—require more than fiscal prudence; they demand political courage. A 5% GDP growth rate in 2026, even if achieved, will mean little if more young people are unemployed and more families fall below the poverty line. The informal sector continues to carry the economy yet remains largely untaxed and unsupported—a sign that policy remains biased towards the formal elite. Treasury’s reforms still orbit around revenue collection, not income generation.

The government’s fixation on Vision 2030 as a slogan of hope risks becoming an excuse for deferred justice—an argument that austerity today will yield prosperity tomorrow. Vision 2030 will not be realized through balanced books alone. It will require balanced lives—equitable opportunities, accessible healthcare, and public institutions that serve people before power. This budget, for all its numerical neatness, falls short of that human vision.

Going forward, Zimbabwe’s fiscal architecture must be inverted: not merely reducing expenditure gaps but closing the gap between state rhetoric and social reality. Reducing VAT instead of raising it, truly scrapping or scaling back the IMTT across all currencies, channeling more funds into education and youth employment programs, and insulating social sectors from austerity—these would have been signs of sincerity rather than statistical success.

In its present form, the 2026 budget demonstrates Ncube’s consistency as a prudent manager of numbers but exposes his inconsistency as a steward of people’s welfare. The document reads less like a blueprint of transformation and more like a ledger of survival. It is underpinned by discipline but short on empathy; it speaks of growth but whispers of austerity. Zimbabwe needs both the arithmetic of recovery and the ethics of inclusion. Without the latter, Vision 2030 will remain exactly what it is today—a distant vision, shimmering just beyond the reach of those who wake each morning still wondering how to afford tomorrow.

Lawrence Makamanzi is a researcher and analyst sharing his personal views. He can be reached at [email protected] or 0784318605

Source: NewsDay

For More News And Analysis About Zimbabwe Follow Africa-Press