After two years of intensifying repression and worsening economic hardships, the euphoria that marked the end of Robert Mugabe’s 38-year hold on power is dissipating in Zimbabwe.

The late Mugabe, who ruled the southern African country since Independence in 1980, was toppled in a coup engineered by his lieutenants in 2017.

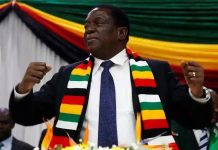

He was succeeded by long-time confidante President Emmerson Mnangagwa whose dramatic rise brought in hope of freedom for many after years of authoritarian rule.

President Mnangagwa promised to steer the country into a democracy and styled his leadership as a “new dispensation.”

“I am soft as wool,” he said at the time.

The former vice president, who was forced into brief exile during former president Mugabe’s last days in power before his triumphant return on the back of a military takeover, largely kept his promise as he finished his mentor’s term.

However, August 1, 2018, the day after the historic polls that gave him a full mandate, marked the turning point.

Soldiers opened fire on opposition supporters demonstrating against delays in the release of presidential elections results, killing six on the streets of the capital Harare.

Human-rights groups said 17 people were killed and several women raped by soldiers after President Mnangagwa unleashed the military to stop protests against a steep increase in the price of fuel in January this year.

The government blocked the Internet as protests raged and analysts say by then the government had resorted back to the Mugabe rule book.

“The resurgence of authoritarian politics in the form of the post 2018 election violence and the violent repression of opposition and civic dissent in January, August and November 2019, marked the predictable path of Mugabe’s legacy,” said academic Brian Raftopoulos.

“The post 2017 Mnangagwa regime very quickly turned into political repression that has defined the multi-layered Zimbabwean crisis since the late 1990s,” he added.

Opposition protests were banned throughout the year as state security agencies said they feared the volatile economic situation could ignite chaos. On the few occasions that supporters took to the streets they were bashed by riot police and several people were arrested.

At least 20 civic society activists and opposition legislators were charged with treason for their alleged involvement in the protests.

Clement Nyaletsossi Voule, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, said that “fear, frustration and anxiety” were growing among Zimbabweans.

After a 10-day fact-finding mission in September, Mr Voule said the deteriorating political, economic and social conditions in the country had killed any hope for change.

“I have perceived that there is a serious deterioration on the political, economic and social environment since August 2018, resulting in fear, frustration and anxiety among a large number of Zimbabweans,” Mr Voule said.

A month later, UN special rapporteur on the rights to food Hilal Elver, warned that the country was on the brink of “a man-made crisis” with millions of people facing starvation.

“More than 60 per cent of the population of a country once seen as the breadbasket of Africa is now considered food insecure, with most households unable to obtain enough food to meet basic needs due to hyperinflation,” said Ms Elver in a preliminary report after an 11-day visit.

A severe drought significantly reduced agriculture output and Zimbabwe is struggling to finance grain imports due to foreign currency shortages.

The drought has also plunged the country of 14 million people into darkness as the main source of hydropower—Kariba Dam—is running dry. Since May, the country has been experiencing 18-hour daily blackouts, which have crippled the economy.