Africa-Press – Zimbabwe. When Zimbabwe’s President Emmerson Mnangagwa described Venezuela as “very far away from Zimbabwe” in response to a question about the dramatic U.S. military capture of Nicolás Maduro in January 2026, the remark was more than merely geographic. It was an accidental admission of a deeper political malaise: an inability, or unwillingness, to situate Zimbabwe within the matrix of global power, law and moral legitimacy.

For decades, Zimbabwe’s foreign policy was shaped by more expansive solidarities. Under Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe and Venezuela, led by Hugo Chávez, forged not merely transactional ties but ideological alignment. Caracas supported Harare’s land reform agenda with financial and political backing at the height of its standoff with the West — a period when both countries found themselves targets of U.S. and European sanctions.

Zimbabwe’s political elite were welcomed in Caracas; Venezuela backed Zimbabwe’s bids in multilateral fora, expecting reciprocity on principle and practice.

Both nations were prominent members of the Non-Aligned Movement, an organisation premised on sovereignty, self-determination and resistance to great power domination. Shared diplomatic frameworks and patterns of resistance to Western pressure made the relationship more than a footnote in either country’s foreign relations.

Yet today, when the global order is convulsed by a crisis that goes to the heart of the UN Charter’s prohibition against the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, Zimbabwe’s leadership has recast its foreign policy as timid neutrality. That recasting is not merely diplomatic posture; it is a stand-for-nothing policy that substitutes intellectual convenience for strategic and ethical clarity.

What Happened in Venezuela?

On 3 January 2026, U.S. special forces conducted a military operation in Venezuela that resulted in the capture of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. This operation involved strikes on multiple targets in Caracas and beyond, and has been widely condemned by international organisations, including the United Nations, the African Union, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Group of Friends in Defence of the Charter of the United Nations, as a violation of international law and the UN Charter.

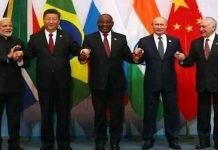

Globally, reactions have spanned the spectrum — from unequivocal condemnation by regional powers like Brazil, to calls for dialogue and respect for international law from a range of states across Asia and Africa. What has been absent from most responses, however, is Zimbabwe’s voice of principled engagement.

A President on the Fence:

At the World Governments Summit in Dubai in February 2026, Mnangagwa’s answer was cautious to the point of vacuity.

By concentrating on distance and information uncertainty, and by framing Zimbabwe’s foreign policy as “friend to all, enemy to none,” the response effectively abdicated Zimbabwe’s voice on a matter of core interest to developing countries and the multilateral system.

Such a position is sometimes defended as necessary pragmatism, especially in a world where alignment with greater powers carries economic and political costs.

But there is a difference between strategic neutrality and neutrality born of intellectual and moral timidity.

Geography does not inoculate a nation from global politics; Zimbabwean diplomats should know this better than most, given the very real interventions in southern Africa in the 1970s and 1980s that reshaped the continent.

Why This Matters for Zimbabwe:

The stakes are not abstract.

Zimbabwe is campaigning for a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for 2027–2028. A leadership bid premised on upholding the UN Charter is undermined when the country cannot articulate a clear position in defence of that same Charter when it is breached.

South Africa under Jacob Zuma was one of two Africa’s representative in the UNSC.

South Africa shocked the world when it cast the deciding vote for the invasion of Libya 🇱🇾, leading to the murderous execution of Muammar Gaddafi.

Who knows what Zimbabwe under Mnangagwa will vote for at the UNSC with this vacuous “friend to all and enemy to none” foreign policy? Bombings in Gaza?

Venezuela explicitly backed Zimbabwe’s bid in 2025, presenting it as aligned with defence of multilateralism and sovereignty.

By refusing to condemn or even clearly contextualise U.S. actions in Venezuela, the Zimbabwean presidency has undercut the ideological foundations of its own aspirations on the global stage.

Worse, it sends a message that moral clarity is subordinate to diplomatic convenience — a message hardly befitting a nation that once stood at the forefront of liberation struggles and anti-hegemonic solidarity.

Geopolitics Requires Moral Articulation:

To claim that geographical distance explains a lack of engagement is lazy intellectually and hollow in logic. If the measure of global political literacy were proximity, then the farther one is from Washington, London or Beijing, the less one would understand their policies — a proposition absurd on its face.

Foreign policy is a product of values, interests, and strategic calculation. Zimbabwe’s has increasingly leaned toward transactional calculations at the expense of articulating values that matter to its citizens and to the Global South. Calling for peaceful resolution and dialogue is not inherently wrong — indeed, those principles should underpin international relations. But they cannot be a cloak for evasion when actions clearly contravene international norms.

The post-colonial world did not win the battle for sovereignty only to watch it be hollowed out by selective silence. Zimbabwe’s leaders must recognise that neutrality without principle is not wisdom — it is cynicism dressed up as realpolitik.

Conclusion: We Are Not Too Far to Care:

Zimbabwe and Venezuela may be separated by continents, but they are linked by shared histories of resistance and of striving for sovereign voice. To dismiss global crises as “too far away” is to ignore the interconnectedness of our world and the obligations that come with seeking a seat at the table of global governance.

In international politics, distance does not diminish relevance — silence does.

Well, this is a President who is on record asking, “Who needs ideology when people are making money?”

Without ideological identity we cannot stand for anything in global politics.

For More News And Analysis About Zimbabwe Follow Africa-Press