By Ilídio Manuel

Africa-Press – Angola. The Angolan Head of State chose the world’s biggest platform a few days ago, more specifically the 79th General Assembly of the United Nations (UN), in New York, to denounce an alleged lack of collaboration from certain Western countries in relation to the repatriation of money that was (il)licitly taken abroad from Angola, over several years.

In his speech, João Lourenço revealed that, with the exception of the United Kingdom, the other Western countries “arrogated to themselves the right to question the credibility of the Angolan courts, almost wanting to review the sentences issued by them, as if they were extraterritorial appeal bodies”.

In other words, the countries whose names were not mentioned have been questioning the independence and sovereignty of the Angolan courts when, in the President’s view, they should simply accept the “obligatory” nature of the decisions of these bodies.

Could this be one of the reasons why Angola has only managed to recover a “measly” 6 billion to date out of an estimated total of 100 billion US dollars, which disappeared from the country, according to data provided by the PGR’s National Asset Recovery Service?

Although he did not say so expressly, the President nevertheless let slip a certain frustration regarding the much-touted fight against corruption and impunity, attributing part of the blame for this failure to certain Western countries which, according to him, have placed obstacles to the repatriation of monetary flows.

Since launching the unprecedented asset recovery campaign in 2017, João Lourenço has faced a series of setbacks and limitations, many of which are difficult to overcome and require skill in their handling.

One of the obstacles that may be hindering the capital repatriation process has to do with the fact that a good part of this money left the country legally, that is, via the formal banking system. This means that it was not transported in bags in secret, under cover of night, but in broad daylight.

Even knowing or suspecting the shady origin of this money, the receiving countries did little or nothing to prevent it from entering and circulating within their banking circuits, which helped to a certain extent to strengthen their economies.

In down-to-earth language, it would be said that every dollar stolen from Angola not only served to give milk to a European child to the detriment of an Angolan one, but also helped to generate wealth in the receiving countries.

One of the first signs of the complex process of repatriating the money came in 2018, when João Lourenço was on an official visit to Portugal, and the then Portuguese Prime Minister publicly admitted that repatriating the assets to Angola could undermine the local financial system and cause serious consequences for the Portuguese economy. António Costa could not have been clearer.

In other words, the former head of the Portuguese socialist government would be indirectly launching an appeal or laying out the paths for the two countries to reach an agreement, so as not to cause financial imbalances in the Portuguese economy, this country being one of the largest, if not the largest destination for Angolan money.

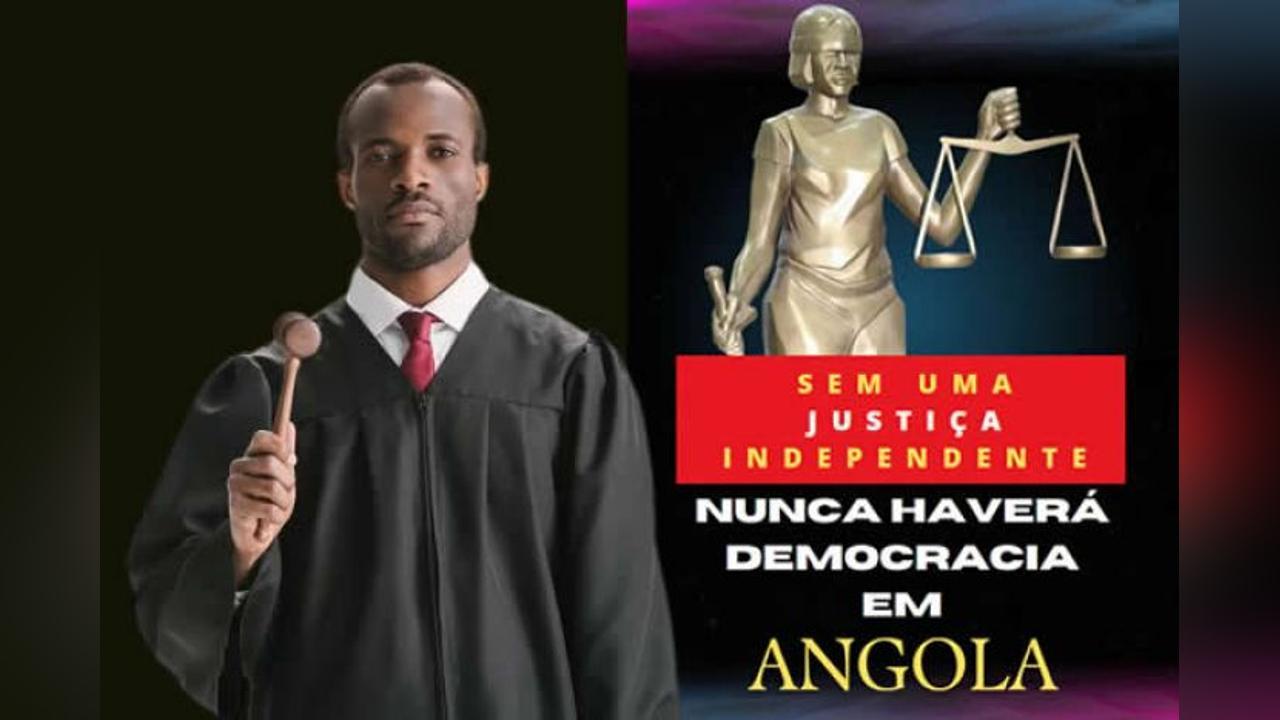

While it is true that there is a certain resistance from Western countries to repatriating the money stolen from Angola, it is no less true that our country has not done its homework properly, that is, the fight against corruption and impunity has not been accompanied by a reform of the judicial system to reverse the terrible image that our courts have abroad.

João Lourenço therefore has no great reason to complain about the international discredit of our courts, something that results from the systematic interference of political power in the judicial system, its partisanship, as well as the various errors of a procedural nature that have been committed.

When he came to power in September 2017, the President led a relentless fight to “save” Manuel Vicente from the clutches of the Portuguese justice system, who had been implicated in a criminal case of bribery and money laundering involving a Portuguese prosecutor.

It is worth remembering that at the time of the events, Manuel Vicente was not yet Vice-President of the Republic, and therefore did not enjoy the immunity inherent to the position. Despite this, João Lourenço acted with trumpery, to the point of threatening to sever diplomatic relations with Portugal.

At the time, he was so rude to the Portuguese that, in his inauguration speech, he blatantly omitted the name of Portugal, in a ceremony in which the Portuguese were represented at the highest level, through President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa.

Time would prove right those who suspected that the pressure exerted by Luanda was aimed at removing the former Angolan leader from the Portuguese justice system. Proof of this is the fact that the passive agent of the crime, the Portuguese prosecutor Orlando Figueira, is currently serving a sentence of 6 years and 8 months in prison, unlike the former Angolan leader who was never in the least disturbed by the justice system in his country.

The credibility of Angolan justice was not only called into question in this case involving the former Angolan leader, but also in another that took place in Spain, in which Carlos Panzo, a former advisor for Economic Affairs to the President, was listed, and whom Angola had requested to be extradited from Spain, after being accused of bribery and money laundering.

To the extradition request made by the Angolan authorities, the Constitutional Court of Spain responded with a resounding “No”, arguing that: “The Attorney General’s Office (PGR) of Angola and the National Directorate of Investigation and Criminal Prosecution (DNIAP) did not meet the requirements of authorities independent of the executive branch”. In other words, they were bodies directly dependent on the Holder of Executive Power (TPE).

In its decision, the court expressed its fear that if he were to be tried in Angola, Carlos Panzo would not have “effective judicial protection and a process with all guarantees”.

From failure to failure, Angola would later use the same extradition legal institution with the Portuguese authorities to bring Carlos Panzo back to the country, but also without success.

The blunders of justice did not stop there. In 2021, the outcome of the “Abel Cosme case”, former CEO of TCUL, not only bordered on ridiculous, but also once again called into question the seriousness of the Angolan judicial system.

The former manager, who had fled to Portugal after being named in the criminal proceedings of the National Council of Shippers (CNC), was extradited to Angola in September 2021, at the request of the Angolan authorities.

To the surprise of many, once in Angola, he was released by the DNIAP a week after his extradition, on the pretext that he had not fled the country, but that he was absent for “health reasons”.

If we add to this the fact that the Angolan justice system has not lifted a single finger in the face of the serious and abundant accusations of embezzlement and money laundering of which figures from the President’s inner circle, namely Edeltrudes Costa and João Baptista Borges, have been accused, those who accuse our justice system of being guided by selective criteria may be right.

Could it be that, because she foresees serious difficulties in recovering assets, the former deputy prosecutor of the PGR, Eduarda Rodrigues, now in disgrace, defended, at one time, the need for Angola to establish asset-sharing agreements with some countries, especially those that have resisted the return of assets in cash?

ANGOLA24

For More News And Analysis About Angola Follow Africa-Press