Africa-Press – Eritrea. Eritrea’s literary and historical landscape is profoundly shaped by the contributions of Alemseged Tesfai, a figure whose life intertwines the roles of renowned writer, dedicated historian, and freedom fighter. His journey from legal studies to the heart of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) underscores a deep commitment to his nation’s quest for self-determination. This vantage point, forged in the crucible of Eritrea’s struggle for independence, imbues his literary and historical works an unparalleled authenticity and perspective. As a historian, Alemseged has meticulously documented Eritrea’s path from federation to independence, offering crucial Eritrean-centric narratives that challenge external interpretations. His impact extends to the realm of literature, where his plays, such as the groundbreaking “The Other War,” have illuminated the multifaceted experiences of Eritreans during pivotal historical periods, solidifying his status as a key cultural voice.

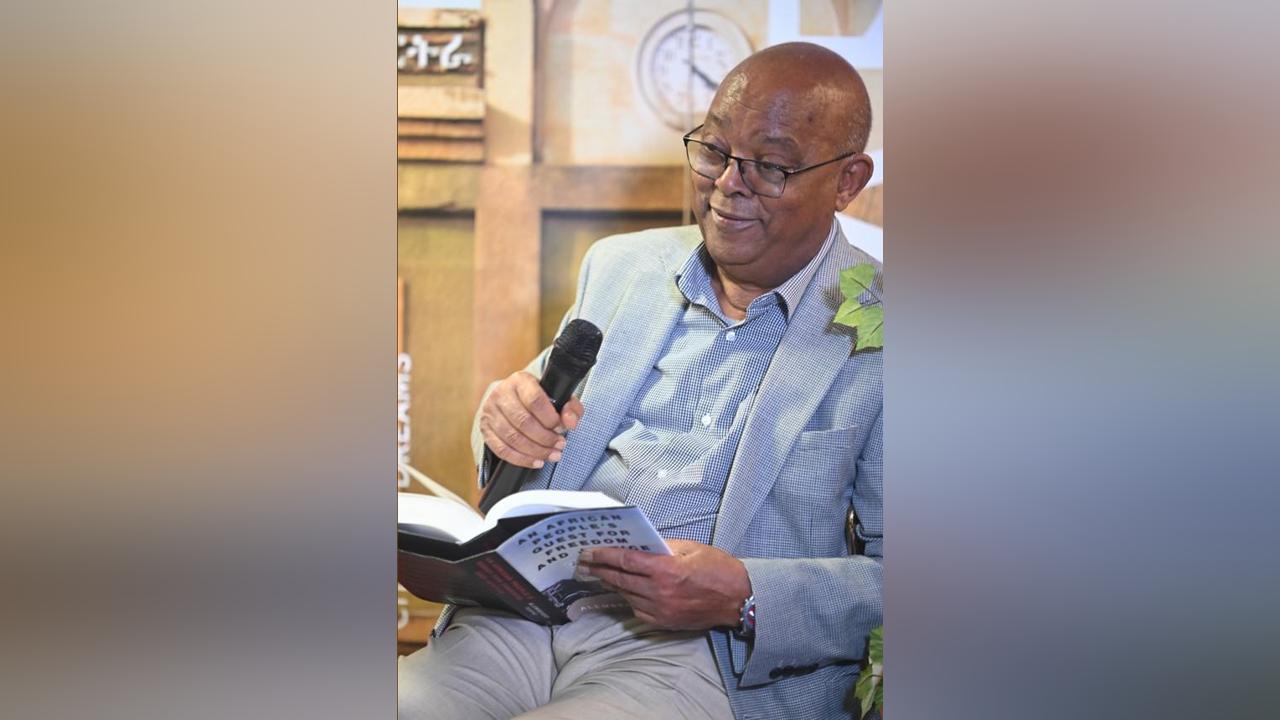

In this illuminating Q&A, we delve into Alemseged Tesfai’s insights as he releases his latest book, “An African People’s Quest for Freedom and Justice.” Drawing upon his extensive experience as both a participant in and a chronicler of Eritrean history, we explore the key themes and messages embedded within this new work.

Your new book, “An African People’s Quest for Freedom and Justice,” delves into a significant theme. What key aspects of this quest do you explore in the book, and what message do you hope readers will take away?

I don’t think that I can point to “key aspects” from the whole theme. With the exception of a few attempts by various writers, the narrative that poses as Eritrean history in global literature has been largely devoid of Eritrean voices, historical sources and collective memory. The whole story had thus to be retold from the Eritrean perspective – the receiving end of an imposed narrative. But this is not done in isolation from the larger Ethiopian narrative and the international support that has been accorded to it an unassailable status. Three processes that determined the fate of Eritrea in 1941-62 period – the Eritrean, the Ethiopian and the US-UK led international dynamics – are, therefore, analyzed in this book with as much objectivity as available resources allow. I hope that readers will have a clearer understanding of the events that led to the Eritrean war of independence and the attendant quest for denied freedom and justice.

Having been deeply involved in Eritrea’s liberation struggle, how has your personal experience shaped your perspective and approach to writing about Eritrean history and identity?

My interest in the necessity of Eritreans claiming ownership over their own history actually started before my direct involvement in the Eritrean liberation struggle. During my studies at various universities in the 1960s and early 70s, I came to realize that Eritreans had been letting others define them in a way that they would not define themselves. Although I wrote a couple of theses that touched on Eritrean history, neither my experience nor the available sources would enable me to tackle the problem effectively. My participation in the armed struggle reinforced my previous belief, especially when the armed struggle was misconstrued and delegitimized as a secessionist movement not worthy of the recognition that it deserved. History and the Eritrean identity were at the centre of the conflict. In 1987, and again in 1997, I was given the opportunity to study, research and write on Eritrean history. My revolutionary experience helped me to identify important issues and to obtain a clearer understanding of Eritrea’s narrative.

Your literary works are often described as deeply rooted in Eritrea’s rich history and cultural heritage. What aspects of this heritage do you find most compelling to explore in your writing?

The ability of the people of Eritrea to live in harmony and mutual tolerance despite their religious, linguistic, ethnic and regional diversity is, for me, the most compelling aspect of the Eritrean character. Beginning with the British attempt to partition the country along religious lines, through to subsequent similar trials, the people have consistently refused to be drawn into strife and illfeelings not of their making. Their traditional conflict resolution strategy in the event of internal conflicts has also helped them keep their balanced relationships. The survival of the Eritrean identity is, to a large part, attributable to this characteristic, indeed this soul, of Eritrean society.

Could you elaborate on the process you undertook to research and ensure the historical accuracy and cultural sensitivity in your narratives?

I spent many months examining the primary sources available at the RDC, the newspaper articles and political speeches from the period; the Eritrean Government, Assembly, Supreme Court documents and files; the Ethiopian, “Federal”, UN, British and American documents, etc. I travelled to Addis Ababa, London and New York for documentation and interviews. In an attempt to represent the cross-section of Eritrean society, I tried to be as inclusive of the diversity in our society as I possibly could. Interviews with major figures from the period were of crucial importance. No book on history can confidently claim perfection and accuracy. I hope that readers will point to me areas where these may be identified and corrected.

Beyond history, your writing also touches upon the sociopolitical landscape of Eritrea and the Horn of Africa. What are some of the key contemporary issues that you feel are crucial to address in your literary work?

Peace is in short supply everywhere in the world these days. Our region is no different. I believe that the factors that unite the peoples of the Horn of Africa far outweigh the issues that divide them. I would like to see history and literature move away from the brinksmanship and intolerance of the past to help open up an atmosphere of dialogue and mutual respect.

For readers who are new to your work, which of your books would you recommend as a starting point to understand Eritrea’s history and culture, and why?

This largely depends on the interest of the reader. For Tigrinya readers, “Wedi Hadera” would be a good start, as it is also entertaining. “Two Weeks in the Trenches,” both in Tigrinya and English, would also be a good introduction to my larger books. Tesfaye Gebreab’s, “The Nurenebi File,” which I translated into English, would also effectively serve the purpose. Readers can then tackle my three Tigrinya history volumes and “An African People’s Quest for Freedom and Justice,” more easily.

Considering the evolution of Eritrean literature and historical scholarship since independence, what are some of the emerging voices and perspectives that you find particularly noteworthy?

It is encouraging to see Eritrean writers, many of them young in age, publishing books. But, publishing books is not, by itself, a sign of progress in literary and historical scholarship. For literature to strive, the ground on which it operates needs to expand; it needs to examine social issues and explore the richness of our people’s and diverse cultures and traditions. Writers need to understand that reading and research are essential prerequisites to literary success. There is a manifest weakness in this area, among many of our writers. Recent works of thorough research, Netsereab Azazi’s, “Ona and Bisikdira;” the late Mekonen Shabay’s, “Dinget ab Agamet;” and Girmalem Tekie’s, “Salina 77,” are among the few books that stand out in terms of the indepth detail and investigation that went into them. I am not forgetting the voices of our poets. But our writers need to be recognized if the “emerging voices and perspectives” are to be “noteworthy.”

As both a participant in and a chronicler of Eritrea’s history, what are your hopes and aspirations for the future of Eritrean society and its place in the broader African context?

My hope, especially in regard to history, is to see Eritrean Historiography and the Eritrean narrative take its proper place in the history of the Horn, Africa and the world. I have concentrated only on one period of Eritrean history. To obtain a composite body of Eritrean history, more writers and researchers need to emerge and be encouraged to the earlier and latter parts of our history. Eritrea has a unique history waiting to be told. Eritrea Profile Staff

shabait

For More News And Analysis About Eritrea Follow Africa-Press