Africa-Press – Eritrea. Located in the volatile Horn of Africa and blessed with a long, unspoiled Red Sea coastline, Eritrea is a nation with a rich, complex, and often turbulent history marked by successive external rules and occupation. After waging one of Africa’s most prolonged and most devastating liberation wars, Eritrea secured independence from Ethiopia in 1991. This multipart series sheds light on the country’s decades-long struggle for freedom and identity.

Origins at the dawn of humanity

Archaeological discoveries in Eritrea’s Danakil Depression – especially in Buya – have revealed hominid remains dating back approximately 1.5 to 2 million years, placing the region at the very roots of human history. Prehistoric sites scattered across the country feature rock art, ancient tools, and artifacts, while evidence of early agriculture and animal domestication dates back to around 5000 BCE.

Moreover, many scholars identify Eritrea as the most likely site of the fabled Land of Punt – an ancient trading partner of the Egyptians, which further emphasizes its significance in early human civilization.

Before the colonial era, various parts of present-day Eritrea experienced intermittent invasions and occupations by foreign powers. Egyptians and Ottoman Turks held sway over coastal cities like Massawa and swathes of the lowlands. Meanwhile, rival warriors, feudal lords, and monarchs from surrounding regions launched periodic, short-lived incursions, often met with fierce resistance.

Italian colonization and the rise of modern infrastructure

In the late 19th century, Italy began acquiring coastal territory and gradually extended its reach inland, seeking to establish a settler colonial state. With tacit British support – motivated by geopolitical rivalry with the French – Italy formally declared Eritrea its “colonia primogenita” (firstborn colony) on January 1, 1890. Massawa was named the capital before Asmara assumed the role in 1897, which it retains today.

Over the next 50 years, Eritrea remained under Italian rule. Eritreans endured systemic exploitation, racial segregation, forced labor, and land dispossession. Education was restricted to basic levels, meant only to serve Italian needs. Eritreans were barred from many parts of Asmara and suffered under colonial apartheid policies.

Yet amid this oppression, the colonial period saw significant infrastructure development and modernization. The period saw the building of ports, railways, airports, hospitals, factories, and communications networks, positioning Eritrea as one of the most industrialized regions in Africa at the time. The Teleferica Massaua-Asmara – a 75-kilometer aerial tramway – was the world’s longest cableway when constructed.

In an enlightening 2006 article, the Eritrean scholar Rahel Almedom wrote how, after assuming control of Eritrea following Italian colonization, “the British had inherited a thriving local economy,” while Brigadier Stephen H. Longrigg, a civilian who from 1942 to 1944 served as chief administrator of the British Military Administration (BMA) in Eritrea, described the country as “highly developed,” and noted that it had, “superb roads, a railway, airports, a European city as its capital, [and] public services up to European standards.”

Additionally, as noted by two Westerners who lived in Eritrea, “In 1935, Asmara, which was made the Eritrean capital in 1897, was the most modern and progressive city in Italian East Africa,” while at the same time, the port of Massawa boasted the most extensive harbor facilities between Alexandria and Cape Town. Other Eritrean cities also reflected progress and industrialization. Tessenei was a hub for transportation and economic activity, while Dekemhare, about 40 km south of Asmara, was referred to as “zona industria” and “secondo Milano” and was full of busy factories and industries.

Critically, the period of Italian colonial rule also forged the basis of an Eritrean state and created its modern territorial boundaries, while contributing to the formation and development of a common, shared social history and unique national identity.

British occupation and post-war betrayal

In April 1941, after the decisive British-led victory at the Battle of Keren, Eritrea was placed under British Military Administration (BMA). Despite British promises of independence in return for assistance against Italian forces, these were quickly abandoned. British propaganda even promised, “Eritreans! You deserve to have a flag! This is the honourable life for the Eritrean: to have the guts to call his people a Nation.” These assurances proved hollow.

Instead, the British plundered Eritrea’s industrial assets and infrastructure, selling them off for profit. Sylvia Pankhurst condemned this exploitation as “a disgrace to British civilisation.” Meanwhile, the BMA sowed division among Eritrean communities, seeking to fragment the territory and portray it as too weak and divided to be viable as an independent state. They aimed to partition Eritrea between the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and imperial Ethiopia.

Federation by force

Ethiopia, too, portrayed Eritrea as economically dependent and politically fragile. In a 1947 speech to the UN, Aklilu Habtewold claimed Eritrea “could not live by itself.” The US echoed this narrative, fearing that an independent Eritrea might fall under Soviet influence during the Cold War. In reality, one of the main reasons the British, Ethiopians, and Americans worked so hard to portray Eritrea as weak and so heavily pressed their claims regarding the country was that it was full of development and considerable economic potential.

On September 20, 1949, the UN General Assembly dispatched a commission to assess Eritrea’s future. The delegation confirmed that the overwhelming majority of Eritreans favoured independence. Pakistani delegate Sir Zafrulla warned, “An independent Eritrea would obviously be better able to contribute to the maintenance of peace (and security) than an Eritrea federated with Ethiopia against the true wishes of the people. To deny the people of Eritrea their elementary right to independence would be to sow the seeds of discord and create a threat in that sensitive area of the Middle East.”

Nevertheless, on December 2, 1950, UN Resolution 390 (V) imposed a federation with Ethiopia, making Eritrea an autonomous unit under the Ethiopian Crown. Sponsored by the US, the resolution prioritized Cold War strategic interests over Eritrean self-determination. The American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles infamously declared:

“From the point of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless, the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country be linked with our ally, Ethiopia.”

Unlike other Italian colonies granted independence after World War II, Eritrea was denied its right to self-rule. Days later, Emperor Haile Selassie declared a national holiday celebrating the “restoration” of Eritrea. During a luncheon attended by the US Ambassador, the Emperor expressed gratitude for America’s decisive role in the UN decision.

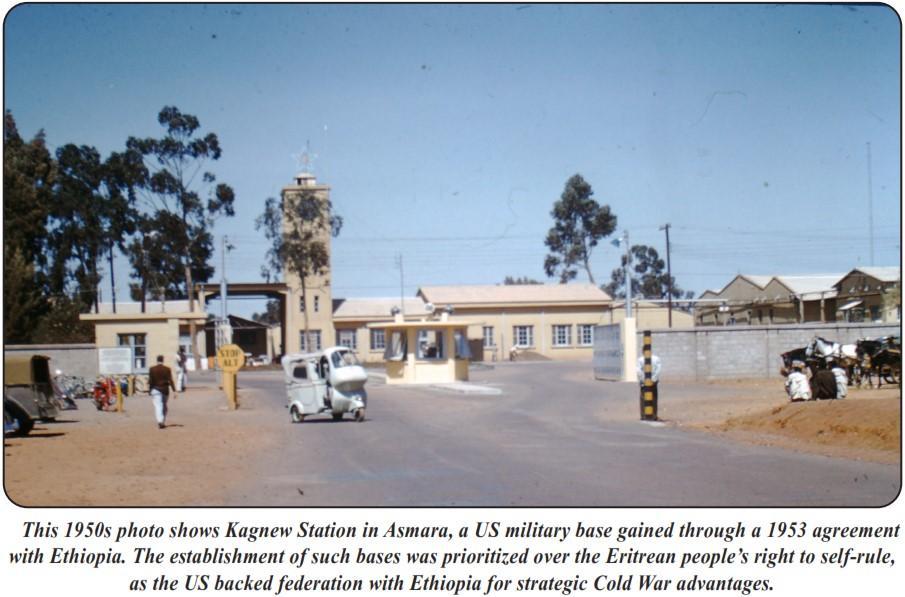

In return, the US gained key military advantages. On May 22, 1953, Ethiopia granted the Americans the right to establish military bases in Eritrea, including Kagnew Station in Asmara, which was then the world’s largest overseas spy facility. Subsequent agreements included comprehensive military aid and training for Ethiopian forces.

The UN-mandated federal arrangement granted Eritrea legislative, judicial, and executive autonomy in domestic affairs. But from the outset, Ethiopia treated it with contempt. The monarchy began systematically dismantling Eritrean autonomy, paving the way for annexation – actions that would eventually spark one of Africa’s longest wars of independence.

shabait

For More News And Analysis About Eritrea Follow Africa-Press