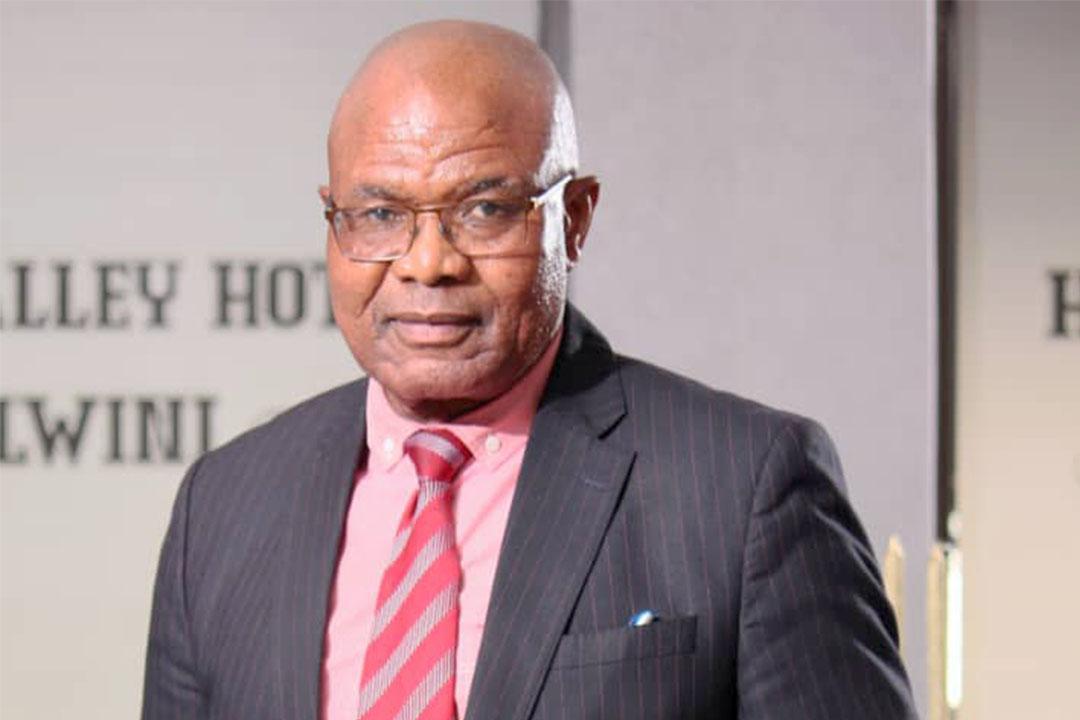

Africa-Press – Eswatini. The momentum for a fundamental shift in Eswatini’s retirement security reached a new zenith this week. In a decisive, strategic endorsement that signals crucial cross-sectoral synergy, Miccah Nkabinde, the Conversion Specialist for the Eswatini National Provident Fund (ENPF), publicly welcomed the advocacy for a universal pension framework.

This critical validation follows the widely-publicised, research-driven statements from Thembinkhosi Dlamini, Executive Director of the Coordinating Assembly of Non-Governmental Organisations (CANGO), calling for comprehensive systemic pension reform.

Nkabinde asserted that Dlamini’s proposal for a national pension fund achieves a critical alignment with the ENPF’s strategic long-term objective of achieving comprehensive coverage and maximising social dividends. This high-level convergence underscores the technical viability and political necessity of adopting a new retirement paradigm for all emaSwati. The consensus between the nation’s principal civil society advocate and its primary pension administrator paves the way for the complex legislative and technical implementation required to secure retirement futures nationwide.

Dlamini’s argument is straightforward yet powerful. Too many emaSwati lack access to retirement savings, while a handful of civil‐servants carry the burden of familial expectations.

His commentary appeared last week and triggered broader debate about the conversion of the ENPF into a universal Eswatini National Pension Fund Bill 2025.

Nkabinde, for his part, described Dlamini’s contribution as “a welcome injection of progressive, forward‐looking thinking” and emphasised that the conversion project benefits from such civil‐society leadership. “It is not often that we find leadership of his calibre championing the structural transformation of social security,” he stated.

Dlamini has long been a voice for inclusive retirement security. He emphasises that even civil servants, who enjoy pensionable benefits, often end up supporting extended family members who work in sectors without retirement provisions, such as textiles and informal industries.

“If a few emaSwati have pensions and the majority do not, those with pensions inevitably feed their relatives at home,” he observes.

Dlamini notes that this insight stems from research he conducted over 20 years ago while at university, highlighting the structural inequities in Eswatini’s current retirement landscape. “The proposed National Pension Fund has enormous potential to succeed, provided all workers are made members by law, thereby mitigating poverty and offering real protection for future retirees,” he says.

Nkabinde emphasised that the conversion project benefits from such civil‐society leadership.

A Vision for Inclusion and Dignity

The underpinning logic of the pension reform is compelling. CEO Futhi Tembe has articulated the case succinctly by noting that for over five decades ENPF has operated under a provident‐fund model, delivering a lump‐sum at retirement; yet rising longevity, inflation and cost‐of‐living pressures render that model obsolete. “This is not just about finance; it is about dignity, inclusion, and empowerment,” Tembe says.

Dlamini emphasises the human dimension of the reform. “Most emaSwati working in textiles and other industries struggle to survive beyond retirement,” he says. “By converting the ENPF into a National Pension Fund, we can ensure that retirees are no longer left dependent on family members or forced into poverty. This is not just a financial reform.It is a lifeline for those currently excluded from social protection.”

The logic is clear. A universal pension model ensures that every economically active liSwati contributes to and benefits from a system that secures predictable income in retirement. Dlamini’s decades-long research and public advocacy provide a foundation for this convergence. His findings, that pensioned civil servants often subsidise non-pensioned relatives, underscore the urgency of creating a universal, legally mandated system. By highlighting the lived reality of ordinary emaSwati, he lends both moral authority and empirical evidence to the reform effort.

Addressing the Key Questions and Misgivings

While the conversion has generated significant interest, it has also prompted important questions, many of which Nkabinde and the ENPF team are actively clarifying to ensure members understand and benefit from the new system.

Eligibility & lump‐sum concerns: Under the new scheme, a minimum 15 years of contribution is required to qualify for a pension; those with less may receive a withdrawal benefit (refund with interest) rather than a full pension.

Loss of lump-sum payouts: The reform prioritises lifelong monthly income over one-off large payments, in order to mitigate old-age poverty risks. Nkabinde argues that lump sums often depleted quickly, leaving retirees vulnerable.

Co-existence with occupational funds: Civil servants’ concerns that the reform might undermine some occupational funds, such as the Public Service Pensions Fund (PSPF) have been addressed. The Bill allows occupational pension schemes, including the PSPF and the new national pension fund to operate side by side. Nkabinde insists the reform is complementary, not competitive.

Informal sector inclusion: The Bill is designed to extend pension coverage to workers previously excluded, including the self-employed and informal sector.

Dlamini has also highlighted that the proposed system mitigates structural inequalities: “By making participation mandatory, we prevent the scenario where a few well-paid civil servants shoulder the retirement burden of the majority of emaSwati. It is about solidarity and shared responsibility, ensuring every liSwati has dignity in old age.”

Strategic Implications for Eswatini

This endorsement by Dlamini and approval by Nkabinde provide more than rhetorical support: they signal a convergence of civil-society advocacy and institutional reform engineering. By combining research-backed analysis and moral authority, Dlamini strengthens the political and social case for reform. The proposed universal pension fund creates a more inclusive, resilient, and equitable retirement system, one that spreads risk, reduces old-age poverty, and ensures that no liSwati outlives their income.

The broad aim is to create a pension ecosystem in which every economically active liSwati is included, not left behind. The reform addresses structural fragilities in the current provident-fund model and aligns Eswatini with international best practice in social protection.

The Imperative Ahead

However, success is not guaranteed simply by alignment of vision. For the reform to deliver, several steps are vital:

Robust public communications: Many workers remain uncertain or misinformed about how the new scheme works. Clear, transparent guidance is essential.

Regulatory clarity and compliance: Strong governance structures, enforcement mechanisms, and regular reporting will underpin trust.

Inclusive implementation: The informal sector, part-time workers, and non-traditional employment arrangements must be captured effectively.

Safeguarding existing rights: Ensuring that current ENPF and PSPF members understand their rights and transition pathways will be crucial for buy-in.

In the words of Tembe, this is more than technical reform, it is a statement of national intent: that every liSwati deserves dignity in retirement, no matter their job, sector, or status. With both Dlamini and Nkabinde now publicly aligned, the momentum is real. The time for action is imminent, and the future of Eswatini’s social-security architecture may be entering a bold new era.

For More News And Analysis About Eswatini Follow Africa-Press