Africa-Press-Ethiopia

In 1984, Tewodros “Teddy” Aklilu was a student at George Washington University and a parking lot attendant in Washington, D.C. He was also the keyboardist in a band with other Ethiopian expats in their early twenties called Admas—Amharic for “horizon.” That year, his mom loaned him the money to press and self-release 1,000 copies of their album, Sons of Ethiopia.

Decades later, this homemade effort has been re-released with detailed liner notes, drawing attention and acclaim from music fans in Ethiopia and beyond.

Aklilu had long ago put Sons of Ethiopia behind him.

“We had forgotten it,” he explains. “It was a labor of love from thirty-six years ago. Then we got a call from this Danish guy Andreas who wanted to reissue this album. We are all excited about the attention.” Since the release in July, the band has been the subject of several interviews, reviews, and social media discussions.

“This Danish guy” is Andreas Vingaard, a record collector living in New York City, a passionate fan of Ethiopian music, and the owner of small label, Frederiksberg Records. At some point, he obtained an original copy of the Admas album on eBay for $400. A few years ago, he began working on the re-release. According to Ethiopian music scholar Sayem Osman, the album has gone viral on Ethiopian social media.

Ethiopian music is distinctive for its pentatonic scale. Ethiopian popular music from the 1960s and 1970s—with its blend of Ethiopian traditional music, jazz, and funk—has reached a mainstream Western audience largely through a series of retrospective albums called Éthiopiques and the 2005 film Broken Flowers starring Bill Murray.

The Admas acclaim seems to derive from the way the album draws from and rearranges “golden era” Ethiopian music with then-fairly-new synthesizer and drum-machine rhythms. Voracious fans of many styles of music, the band also melded traditional Ethiopian influences with aspects of other genres like Ghanaian highlife, Brazilian jazz fusion, Jamaican reggae, and American R&B and jazz.

“Whatever we could get our hands on was our influence,” multi-instrumentalist Abegasu Shiota reflects. “Soul and disco, country was big growing up here in Ethiopia. Anything we could get our hands on was gold. We were into it.”

The band represented a growing diaspora of Ethiopians in Washington, D.C. While some Ethiopians had been coming to the nation’s capital before the 1970s, the numbers increased in 1974 after members of the Ethiopian Army, who called themselves the Derg, overthrew Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie and installed one-party authoritarian rule. When the Derg instituted the violent Red Terror in 1976 and 1977, and later when the country struggled with famine in 1983 and 1984, even more Ethiopians came to D.C., joining friends and communities already settled in the area. Their ability to immigrate had been made easier by the U.S. Refugee Act of 1980, which reduced red tape for those seeking asylum from oppressive governments or civil wars. According to the 2010 Census, D.C. is home to over 30,000 Ethiopian immigrants, making it the largest Ethiopian community outside of Africa.

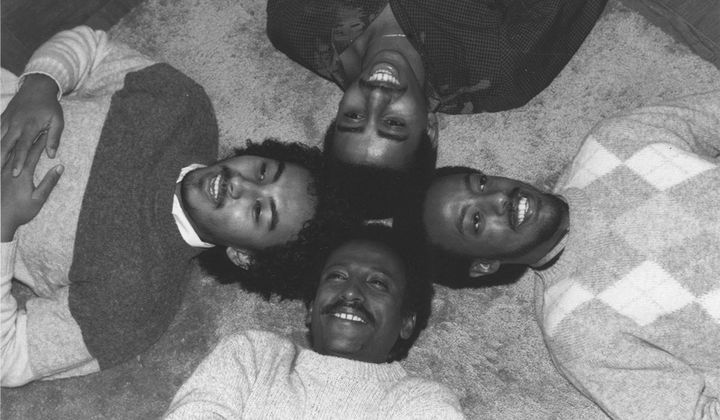

Admas formed in 1984 when Shiota, who is of Japanese and Ethiopian heritage, came to the United States from Ethiopia as a touring musician with singer Muluken Melesse. Shiota stayed in D.C. and began playing with keyboardist Aklilu, bassist Henock Temesgen, and drummer Yousef Tesfaye. Shiota had been in a well-known band in Ethiopia called the Ethio Stars, while the others had been playing in a D.C. Ethiopian cover band, Gasha. Shiota and Temesgen had earlier played together in Ethiopia in a state-sponsored community band. Temesgen had gone to high school with Aklilu, who in 1977 was the first of the four to come to the D.C. metro area.

Admas’s predecessor was Gasha, which was formed in 1981 by Aklilu, Temesgen, Tesfaye, guitarist Hailu Abebe, and vocalists Simeon Beyene and Zerezgi Gebre Egziabher. They played late on Thursday through Saturday nights, and occasionally on Sunday, at the Red Sea Ethiopian restaurant in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of D.C., which was becoming home to many Ethiopian establishments at the time. (“Believe it or not, I played on that same stage on that same corner thirty-some years later, as Red Sea is now Bossa!” Aklilu exclaims.) For a couple of years, the band gigged regularly there to crowds that were nearly all Ethiopian or Eritrean. While Ethiopians and Eritreans would not always go to the same places in later years, Red Sea had both Ethiopian and Eritrean owners, and Gasha singer Egziabher was Eritrean. At the time, Eritrea was still a province of Ethiopia.

“We were doing covers of popular songs,” Temesgen says. “People came to the show because they were nostalgic about that. To be honest, all of us were very inexperienced at that time, not very good then. But since we were the only band around at that time, we became popular. But soon other musicians began coming from Ethiopia, and it became hard to get the same crowds as people got spoiled with other bands.”

While the Ethiopian community here was certainly thinking about what was going on with the Derg back home, Aklilu says the atmosphere at the Red Sea was more cultural than political.

“We were together as one there,” he reminisces. “We played homesickness music. The political issues existed, but we were not part of it.”

Aklilu also remembers seeing some legendary Ethiopian musicians in other nearby venues. “On breaks, I would walk down to this place called Sheba near Café Lautrec, and Girma [Beyene, acclaimed Ethiopian songwriter] would play piano with a bassist and be doing all this abstract stuff. I was mesmerized even though I didn’t fully understand it.”

The artists also have other fond influential memories of live music in D.C. Aklilu says he loves D.C. go-go, calling it “the most African of African American genres.”

“For a while we played at a club called Negarit on Georgia Avenue that had go-go concerts [in the second-floor Ibex club] every Sunday,” Temesgen adds. “Chuck Brown was there playing upstairs, and we were playing downstairs.” They also fondly recall seeing jazz bands at the Saloon in Georgetown, Takoma Station, and Blues Alley.

As Aklilu explains, the venues shaped the structure of D.C. Ethiopian bands.

“The D.C. restaurants are narrow and long. Houses turned into clubs and restaurants. I have a feeling that forced Ethiopian music to get smaller,” contrasting with the big bands back home. He notes that “the unwillingness of owners to pay” also led to some clubs hiring just individuals or duos. Unable to get paid more at Red Sea, Gasha briefly moved to an Eritrean club called Amleset, run by Eritrean krar player and singer Amleset Abay, before the band broke up at the end of the summer of 1983. The dissolution made room for Admas the following year, when Shiota joined with three of the Gasha members.