Africa-Press – Ghana. Habitat loss and direct persecution of large carnivores are well-documented threats, but the role that cultural demand plays in the fortunes of many species of wildcats is poorly understood. In a study published in March 2025, researchers found that alongside servals and cheetahs, leopards and lions — both classed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List — are among the most commonly exploited species.

Study co-author Marine Drouilly told Mongabay by email that many conservation efforts fail because they don’t consider local beliefs and traditions.

“While threats such as habitat loss and poaching for bushmeat are well-documented, cultural practices — such as the use of skins, bones, and other parts in rituals, traditional medicine, or social status symbols — are often overlooked,” said Drouilly, the carnivore monitoring coordinator for West and Central Africa at wildcat conservation NGO Panthera.

Genet, serval and black-backed jackal skins, at the Faraday market, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017.

There are more than 2,000 ethnolinguistic groups in Africa, each with its own distinctive customs. “Many of these cultures have traditions of using wildlife for purposes such as attire, zootherapy (medicine) and bushmeat, but the pervasive usage of carnivore parts, especially in traditional ceremonies, has not received the level of consideration it seems to warrant,” Drouilly and her fellow researchers write.

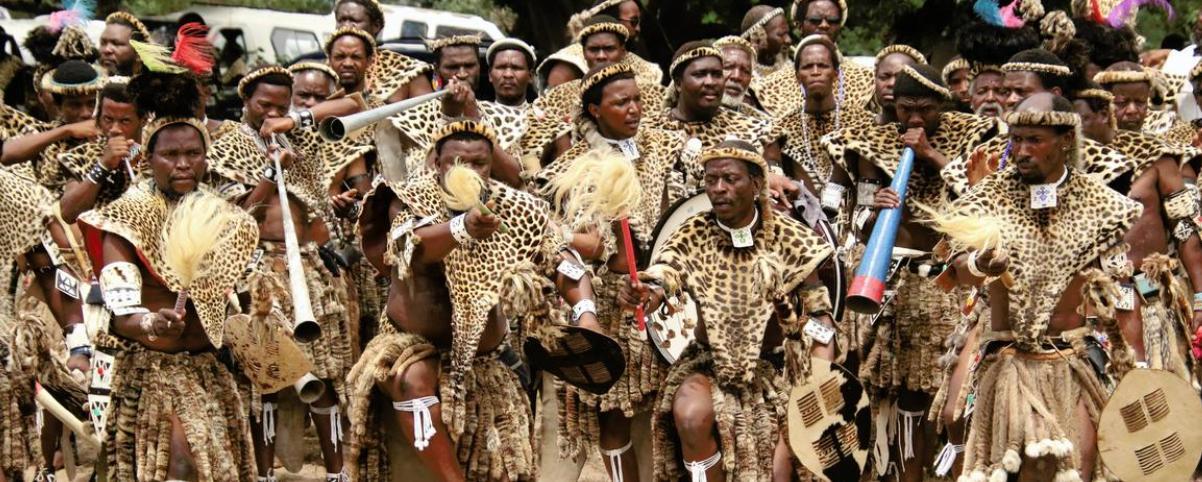

Among the better-known examples of cultural demand for wildcat parts is the Nazareth Baptist Church in South Africa, also known as Shembe, for whose 9 million members leopard skins are an essential element of ceremonial regalia. Leopard skins are also a symbol of royalty among the amaZulu, Barotse and Ngoni kingdoms in Southern Africa.

Panthera commissioned the study to systematically identify and characterize the current use of wildcat products for cultural reasons across the continent.

The researchers reviewed nearly 600 accounts of customary use of 33 African carnivore species in academic journals and elsewhere published between 1907 and 2020. They also analyzed evidence from 555 YouTube videos. The documentation covered 48 of the continent’s 54 countries, ranging from Algeria to South Africa, and Djibouti to Senegal.

They found widespread traditional use of skins, claws, teeth, bones and tails of wildcats for purposes like attire, traditional medicine and bushmeat. Leopards (Panthera pardus) featured most frequently, followed by lions (Panthera leo), servals (Leptailurus serval) and cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). The most frequently recorded uses were of a variety of spotted carnivore skins worn by traditional leaders, healers and participants in cultural festivals. Non-attire uses such as for traditional medicine, rituals and bushmeat, as well as musk used in fragrances, were recorded in three-quarters of the countries surveyed.

The end users ranged from members of relatively new religious groups like the Shembe church, to political leaders, to Indigenous peoples.

The researchers say their intention with this study is “not to unnecessarily vilify cultural and customary practices,” but to promote an informed appreciation of their potential impacts on wildlife species.

“We also aim to foster awareness and, where appropriate, encourage the integration of the cultural significance and implications of these practices into conservation frameworks and thereby avoid irreparable population depletion — without endorsing their utilisation as Trojan horses to conceal illicit, population-threatening activities,” the researchers write.

The study is also relevant to societies across Asia, Latin America and parts of Europe and the U.S., which all have traditions involving carnivore parts for rituals, medicine and status symbols, Drouilly said. She added conservation programs in other parts of the world could also draw on the report’s findings, for instance addressing the use in Asia of body parts from tigers (Panthera tigris), or trafficking of jaguars (Panthera onca) in Latin America.

Tarik Bodasing, a technical adviser in wildlife and forest crime in Liberia for the U.K.’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), who wasn’t involved with the study, said the research draws attention to the negative impacts of consumptive use of wildlife.

“There are no positive impacts of such use,” he said. “Unfortunately, the world and society has shown that when it comes to cultural practices, it’s almost always the wild species that suffers from the type of use, in particular trade in skins.”

Bodasing said this kind of research provides policymakers with information needed to guide conservation decisions for the conservation of the targeted species.

Ecologist and evolutionary biologist Philip Muruthi, vice president for species conservation at the Kenya-based African Wildlife Foundation, took a more positive view, saying the study points to how religious and cultural communities might be engaged in protection of carnivores.

“It shows that local communities value the species as exemplified in their use of the skins, etc. for certain symbolic purposes. But such utilization should not jeopardize the species now and in the long term,” said Muruthi, who wasn’t involved in the study. “Let scientists work with the authorities and communities to manage the species in their natural ecosystems. Communities too should embrace science to learn more about the species and how their cultural practices can affect the species they so much cherish.”

This is aligned with what the researchers themselves hoped to achieve, Drouilly said. “This study, by recognizing the scale of cultural demand, can help conservationists better understand the full range of pressures on these species,” she said. “By identifying the cultural contexts in which carnivores are used, conservationists can also design interventions that are more culturally sensitive and locally accepted.

“The purpose of the research was ultimately to help inform future engagement with culturo-religious groups and the co-development of conservation strategies aimed at reducing the pressure on key wild cat populations,” she added.

mongabay

For More News And Analysis About Ghana Follow Africa-Press