SHAUKAT ABDULRAZAK

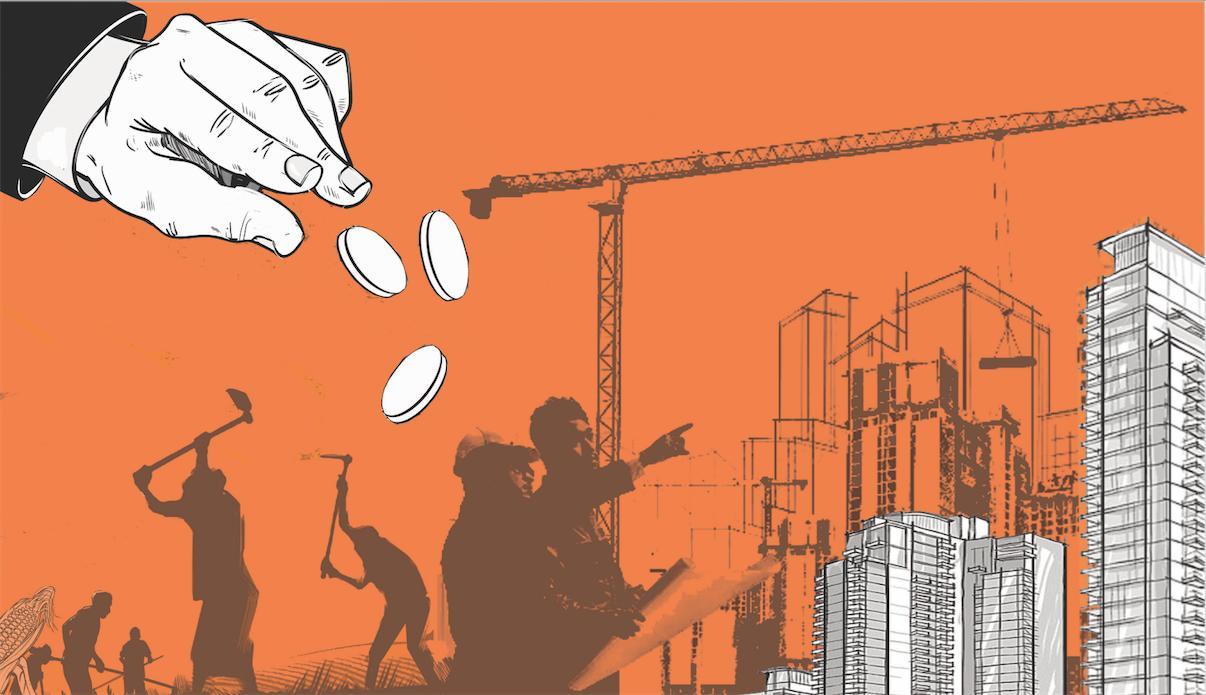

Africa-Press – Kenya. Kenya may be on the brink of its most consequential economic decision since independence: committing two per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to science, research, technology and innovation (STI) as stipulated in the STI Act, 2013.

If implemented effectively, this move could fundamentally shift the country from a consumption- and commodity-driven economy to a knowledge-based, innovation-led one, positioning Kenya on a credible path towards first-world competitiveness.

His Excellency President Dr William Ruto, during the State of the Nation address, explained it well: “We must actualise the National Research Fund, moving from the current 0.8 per cent of GDP to two per cent, and grow the fund to Sh1 trillion over the next 10 years.”

At today’s economic size, Kenya’s GDP is estimated at about Sh17.9 trillion. Two per cent of this amounts to roughly Sh358 billion annually. This is not a token allocation. It is a deliberate, structural investment on a scale large enough to change incentives, institutions and outcomes across the economy.

Over several years, I have observed with interest the potential in our human capital, alongside growing frustration over inadequate research funding. Our youth are hungry for innovative ideas, eager to be heard and funded.

Globally, countries that transformed themselves into advanced economies, such as South Korea, Finland and Israel, did so by consistently investing between 1.5 and 3 per cent of GDP in research and development.

Kenya’s proposal places it firmly within this proven range. The journey has already begun through the creation of the State Department of Science, Research and Innovation, which follows the path of H.E. the President’s vision of “Going to Singapore.”

Many will ask: where would the money go? Here are some proposals that can be explored with stakeholders. Under the proposed framework, the Sh358 billion would be strategically distributed to build a national research and innovation ecosystem rather than being scattered thinly.

Around Sh107 billion (30 per cent) would go to national research institutions, which are responsible for mission-oriented research in areas such as agriculture, health, climate resilience, energy and industrial development.

These institutions would receive a mix of stable baseline funding and performance-based financing tied to measurable impact, including patents, technologies, policy solutions and adoption by industry.

Another Sh125 billion (35 per cent) would be allocated to public universities, recognising their dual role as producers of human capital and engines of innovation. Universities would use the funds to support postgraduate research, modern laboratories, digital research infrastructure, innovation hubs and university–industry collaboration.

On average, each public university would receive about Sh3 billion annually for research and innovation, enough to fundamentally change their role in national development. Currently, research in most universities is almost in intensive care, while meaningful innovation is yet to take off.

A further Sh54 billion (15 per cent) would be set aside for competitive national research and innovation grants, open to universities, research institutions, start-ups and public–private consortia.

This would ensure excellence and relevance, with funding flowing to the best ideas that address national priorities such as food security, healthcare, climate adaptation, artificial intelligence, advanced manufacturing and emerging technologies, using a cluster approach.

To avoid duplication and raise quality, Sh36 billion (10 per cent) would be invested in shared national research infrastructure, including high-end laboratories, data and computing facilities, and centres of excellence accessible across institutions and regions. This would help break the silo mentality and build a vibrant, coordinated ecosystem.

Crucially, Sh25 billion (seven per cent) would be dedicated to commercialisation, incubation and technology transfer. Too often, Kenyan research ends up in journals rather than the marketplace. This funding would support patenting, prototyping, technology transfer offices, incubators and accelerators, turning ideas into products, companies and jobs. It would also help Kenya regain a stronger position in the Global Competitive Innovation Index.

Finally, Sh11 billion (three per cent) would be used to catalyse public–private partnerships (PPPs), encouraging industry to co-invest in research, sponsor innovation chairs and integrate Kenyan research into global value chains. Some of the funds could be used to leverage the internationalisation of STI through science diplomacy.

This is not an elite academic project. It is about jobs, incomes and resilience, with high dividends for society as a whole. In the short term, the investment would create thousands of high-skill jobs for researchers, engineers and technicians, while upgrading laboratories and facilities across the country.

In the medium term, it would enable new start-ups, import substitution and the growth of high-value manufacturing and technology exports. In the long term, it would raise productivity across the economy, the single most important driver of sustainable income growth.

For agriculture, this means climate-resilient crops, precision farming and value addition. For health, it means local diagnostics, pharmaceuticals and digital health solutions. For energy and climate, it means home-grown clean technologies. For young people, it means opportunities beyond informal employment.

The inevitable question is whether Kenya can afford Sh358 billion a year. The better question is whether Kenya can afford not to. We are already spending only 0.8 per cent of GDP. Our President has consistently promoted doing things that are not necessarily popular, but are right. This is one of them.

This is not consumption spending; it is productive investment. Innovation increases the size of the economy, expands the tax base and reduces long-term fiscal pressure. Countries that invest in research and innovation grow faster, earn more and depend less on imports and aid. This approach will enable Kenya to achieve more with less, for more.

Strong safeguards are also proposed: independent audits, digital grant management systems, performance-based disbursement and parliamentary oversight. Funding would be tied to results, not promises. We have the people and the know-how to drive this to fruition.

In my opinion, this would mark a strategic turning point. Kenya’s development challenges, such as unemployment, low productivity and vulnerability to climate shocks, cannot be solved by traditional spending alone. They require new knowledge, new technologies and new industries.

Committing two per cent of GDP to science, research, technology and innovation is not just a budget line. It is a statement about the kind of country Kenya intends to become: one that competes on ideas, talent and innovation rather than cheap labour and raw materials.

If implemented with discipline and vision, I am confident that this investment could mark the moment Kenya decisively turned towards a first-world economic trajectory, built not on chance, but on science.

Source: The Star