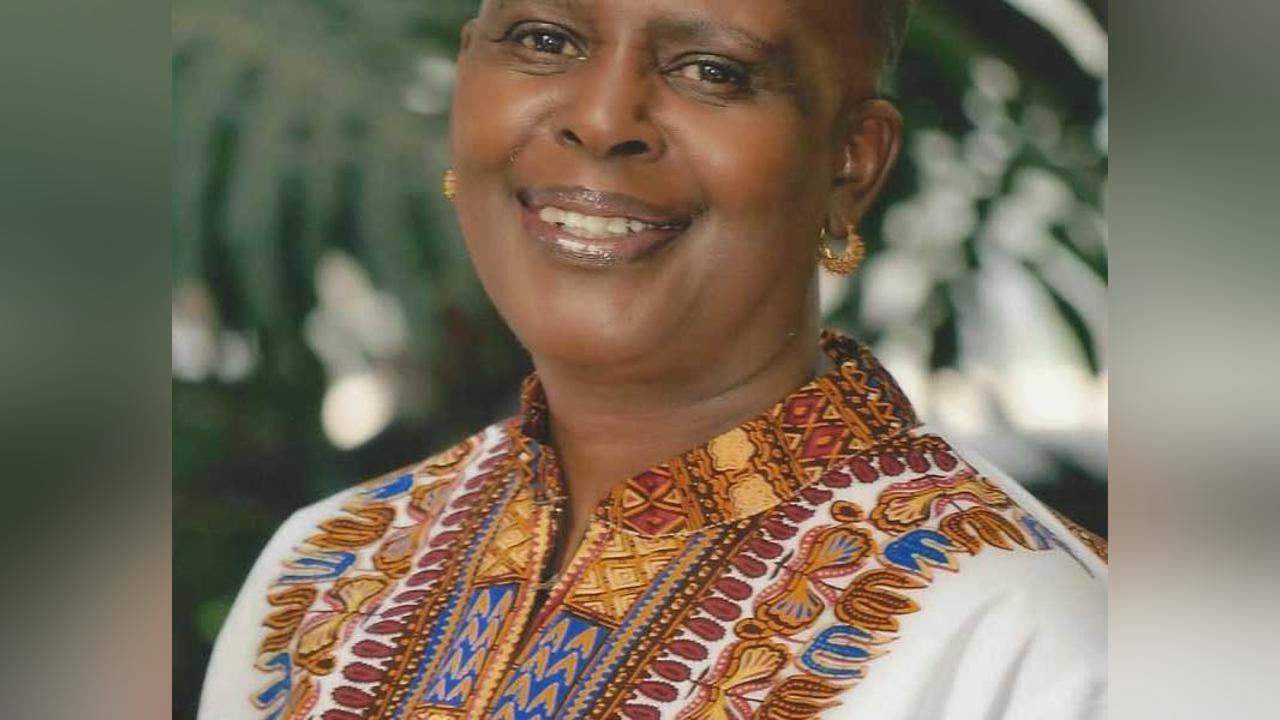

Africa-Press – Lesotho. There is an elderly African woman in Harare, Zimbabwe, who has turned her house into an archive of music and culture and people visit that house for old music and rare pictures of musicians! Joyce Jenje-Makwenda is a journalist, producer and performing artist.

She is an independent scholar, archivist, historian, researcher, author, lecturer and ethnomusicologist. She has more than 30 years of experience covering areas of early urban culture, music, politics, education, religion, media, fashion, sex, sexuality, cultural issues and women’s histories in Zimbabwe.

Her house is now formally called the ‘Joyce Jenje-Makwenda Collection Archives’. It is a private social history archive located in her house in Harare, hosting materials such as video and audio interviews on music, transcriptions, press cuttings, photographs, vinyl LPs and artefacts, that include instruments, gramophones and typewriters for scholarly and historical purposes.

But that is not all! Joyce Jenje-Makwenda’s book of 2005 is something to talk about too. It is on Zimbabwe township music. It is both informative and exhilarating.

It offers the reader an over 75-year flitting glance into different aspects of a musical form loosely tied up and called ‘Township Music’ in Zimbabwe and the world of black people in general.

It is called Zimbabwe Township Music. This collection is difficult to place for various reasons. One is torn between categorising it as serious history or coffee-table book.

The beautiful pictures of beautiful musicians of various generations from Harare to Bulawayo makes one forgive the sometimes restless and scanty details on each star and epoch.

The impression you get from this book is that Joyce was overtaken by a whirlwind at some point and decided to write about every beloved musician and every version of township music.

She is inspired and relentless. She is clearly indebted to each of the musicians covered here. And many of them great names; Moses Mafusire, Sonny Sondo, Lina Mattaka, Simangaliso Tutani, Roger Hukuimwe, Louis Mhlanga, Jacob Mhungu, Alick Nkatha, Sarah Mabhokela.

. One feels Joyce Makwenda’s love for each of them in this breathtaking fast-paced narrative. This is a labour of love and care.

The pictures breathe passionate life from the page and you cry with panoramic joy as you go through this book. The pictures compete against each other and even almost outdoing the narrative.

Dorothy Masuka’s pictures are the most outstanding. Turning the pages, you realise that during her days, Dorothy could ‘pose’ for a ‘photo’. She comes across as a timeless African beauty.

Tallish, dark and with a full bust – she is a suitable model woman from the country between the Zambezi and Limpopo. In her more recent photographs, in this book, she is chubby, less cheerful but clearly combative, with her eyes closed as she belts out into the mike.

Described here clearly as the best ever woman musician from Zimbabwe, Dorothy sang for over 50 years! She went to school in South Africa from where she discovered her voice.

Sophiatown swallowed her and she shared the stage with other great women musician like Dolly Rathebe and Miriam Makeba. Penning great and timeless classics like ‘Hamba Notsokolo’ and ‘Imali yami Iphele eshabeni,’ Dorothy came back home, crossed borders into Malawi, Zambia and England.

Known simply as ‘Dotty’, she was once married to Dusty King, a great soccer star of the 50’s. And her single wish now: “Someday a local football stadium be named after her former husband.

The several pictures of Josaya Hadebe in this book portray a handsome African cowboy with no horse! He should have broken many girls’ hearts in the 1940’s and 50’s.

He played ‘Omasganda’ and his favourite tunes tended to be ‘derogatory and vulgar. ’ However he recorded over 15 songs with Gallo recording company. And the crowds just loved Hadebe!

When he visited the Bantu Sports club in Johannesburg in 1951, he caused a riot ‘as the crowds followed him through the tunnel, obstructing the soccer spectators from all sides of the field.

’ However for Joyce, one Augustine Musarurwa must be the most outstanding male Zimbabwean musician of all times. His prominence in this book is done justice by a very close and touching narrative of his diary.

His song ‘Skokian’ (an illicit township brew) is a song that crossed borders and various musicians made numerous versions of it. These include the great jazz trumpeter, Louis Armstrong himself, Nico Carsten, Robert Delgado, Sandy Nelson, James Last, Paul Lunga and others.

Born in Zvimba at Musarurwa village, Augustine Musarurwa was not only a world-class saxophonist but also a decent policeman with a knack for the three-piece suit.

When the African-American musician, Armstrong, made his famous visit to Rhodesia in 1960, Musarurwa personally paid tribute to Augustine and played alongside him.

Later, in 1970, even Hugh Masekela made his own version of Musarurwa’s Skokian. Joyce Jenje Makwenda’s definition of Township Music is all-embracing and not limiting.

It is defined as music that originated in the new urban centres in the 1930’s and grew from strength to strength up to the 1960’s and is still growing after slowing down in the 1970’s because of the war of liberation and exile.

It is a fusion of many traditional African music forms from the whole Southern African region like tsabatsaba, kwela Omasganda, marabi and others. There is also fusion with African-American jazz from America.

The township musicians played guitars, saxophones, and pennywhistles. They also employed vocals and foot-stamping to provide entertainment in the growing townships.

The first organised Township Music was a group from Mbare called Bantu Actors that was led by Kenneth Mattaka in 1932. Besides being a wholesome book that asks the reader to browse on and on, Makwenda’s book has some useful sub-sections.

In the ‘Recording History’ section, one learns that the recording of music in Zimbabwe started in Masvingo (then Fort Victoria) in 1929. Hugh Tracy who was interested in collecting African folk music did the recordings.

Individual musicians got prominent recording by Gallo in the 1940’s. Josaya Hadebe, George Sibanda and Sakale Mathe were some of the very first to be recorded.

In the section called ‘Venues’ one learns about the centrality of venues like Mbare’s Mai Musodzi and Stodart halls and Bulawayo’s Macdonal and Stanley halls in the development of Township Music.

The story of an Asian man called Mohammed Bhika or Karimapondo is also touching. He built the Bhika Brothers restaurant to allow blacks to have a decent spot to have meals and drinks and music.

Africans and Asians were not allowed in the whites only city centre spots. Josiah Chinamano was reported in the African Daily News of 17 November 1956 to have said, ‘the restaurant is a real pride to all Africans who will patronize it.

’ In such places township music blossomed. The ‘Kwela Music’ section of the book has a more interesting scenario. Kwela music is pennywhistle music.

It was first played by the street side, attracting both black and white passersby who were quickly displaced by the police as Kwela usually indicated that there was some gambling going on nearby.

The police would order those arrested to climb into big vans and would shout “Kwela! Kwela!” and that became the name for this sharp music. Spokes Mashiyane is considered the most prominent Kwela musician.

There is a way in which township music tended to express the presence of black folks in the urban centres. It became a rallying point for black people and the colonialists tended to disperse people who congregated around an Omasganda or Kwela musician.

It is no mistake that names of some nationalists like Daniel Madzimbamuto and Webster Shamu are associated with either recording or general development of Township music.

Although Jenje-Makwenda’s book is not and could not have exhausted all issues to do with township music it is a very useful starting point in understanding both the music and the times.

There is need for other writers to go into some sub-themes and explore them in greater detail. This won’t be easy though because Township music has resurfaced again in Zimbabwe with the likes of Tanga weKwaSando, Dudu Manhenga, Prudence Katomeni and others.

But that is not all! Joyce Makwenda has another book called Women Musicians of Zimbabwe: a Celebration of Women’s Struggle for Voice and Artistic Expression.

It was published in 2013. In this book she chronicles the lives of virtually all Zimbabwean musicians up to 2013. For this book, she was honoured by female musicians in the country for playing a significant role in promoting women participation in the music industry.

The event occurred a year later in 2014 at the then Book Café in Harare as part of its celebrations to mark World Women’s Day. In an interview with The Patriot, Jenje-Makwenda said she wrote the book after realising the low representation of women in the music industry.

“What struck me most during my youth days, and a trend which has continued today, is that in Zimbabwe very few women take music as a career, unlike men,” Jenje-Makwenda said.

“If they do, they are either employed as backing vocalists for male musicians, or dancers.

The book is therefore, a celebration of women’s struggle for voice and artistic expression in very challenging circumstances. It is a tale of resilience determination and triumph.

”

Jenje-Makwenda further said her book revealed that most women in Zimbabwe were failing to realise their full potential in the music profession due to stereotyping from the society.

“I interviewed more than 100 women including the young and old, new and seasoned musicians, and corroborated the interviews with oral history and archival materials, which included newspapers and books,” she said.

“I felt the need to explore the role played by women in the development of music genres in Zimbabwe and to explore why there are very few women musicians in Zimbabwe compared to men,” she continued.

In her book, Jenje-Makwenda profiles various female artistes who have contributed to the development of the music industry in the country that included Lina Mataka, Susan Mapfumo, Stella Chiweshe, the late Chiwoniso Maraire, Dudu Manhenga, Selmor Mtukudzi and Prudence Katomeni-Mbofana among others.

But that is not enough yet! Her novel, Gupuro of 2006, deals with gender related issues affecting African women in developing countries such as her Zimbabwe.

It is about the contradictions that the rise of the middle class in the townships often went through. She also has another novel in Ndebele called USenzeni, published in (2007) which tackles similar issues. Makwenda was born in 1958, in Mbare to David Jenje and Canaan Matiza Jenje. She is the first born of that family.

She has managed to scoop many awards in her career that include, ‘Best Television Producer of the Year’ in 1993, ‘Second best Television Producer’ in 1994, ‘Freelance Woman Journalist of the Year’ in 1999 and the ‘Population Development and Gender Writer of the Year’ in 2002, among others.

When she was growing up, she enjoyed and loved music. She was very artistic not only in music but remembers designing and making her own dress at seven years, a very tender age.

Makwenda has been the recipient of the 2017 ZCCD (Zimbabwe Cultural Centre of Detroit) Research Resident in partnership with the Penny Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series (University of Michigan) and Njelele Art Station in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Her month-long residency was intended to be about researching cultural connections between Detroit and cities in Zimbabwe, focusing on the role of music in early urban culture.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press