Africa-Press – Lesotho. The western city as portrayed in mainstream African poetry is a terrible space for Africans. The city, indeed, comes across as a space that is amazing to the visiting African poet or the African artist who dwells in it.

The city amazes and mesmerises the African poet through its foreignness, its brutality and its capacity to be the quintessence of the dehumanisation of the conquered African.

In South Africa, for example, the urban poet Mongane Wally Serote, has a tantalising poem called “City Johannesburg. ” In that poem, the city is shown as the playground of oppressive laws like the mandatory pass books under apartheid.

It is in the city where one vigorously searches for the pass book in front of the vicious apartheid police:

“This way I salute you:

My hand pulses to my back trousers pocket

Or into my inner jacket pocket

For my pass, my life,

Jo’burg City.

When the poet says, “I salute you” to Jo’burg, he is only being ironic. In the apartheid city the black man shrinks in front of apartheid. Serote is talking about fear and not respect.

The city is also the scene of the back-breaking eight hour job and when one goes back to his people in the township at the end of the day, he is actually tattered and torn. One goes back home in order to die. The poet rants and raves at the city:

“That, is all you need of me.

Jo’burg City, Johannesburg,

You are dry like death,

Jo’burg City, Johannesburg, Jo’burg City…”

The city is a reminder of man’s lack of life even when he eventually goes back to his African village, he goes back in order to die after having lived in the harsh and oppressive city:

“And as I go back, to my love,

My dongas, my dust, my people, my death,

Where death lurks in the dark like a blade in

the flesh,

I can feel your roots, anchoring your might,

my feebleness

In my flesh, in my mind, in my blood,

And everything about you says it,

That, that is all you need of me.

Serote is a great stylist who demonstrates a wide understanding of poetic methods from across the world in order to fashion out his own. He was born in 1944.

He is widely known as a poet, novelist, political activist, exile, member of the Black Consciousness Movement and African National Congress, Commander in uMkhonto weSizwe and Member of Parliament in democratic South Africa.

He became involved in political resistance to the apartheid government by joining the African National Congress and was arrested and detained for several months without trial. The Mozambican poet, Noemia Desouza views Jo’burg and its gold mines in more or less the same way.

She writes about a fellow countryman reduced to nothing in the mines of the Rand:

“And stunned,

Magaica lit a lamp

To search for his lost illusions,

For his youth and his health which stay buried

Deep in the mines of Johannesburg

Youth and health,

The lost illusions

Which will shine like stars

On some lady’s neckin some City’s night.

There are many such poems across the continent, showing how many lost all to this city in the form of migrant labour.

Carolina Noémia Abranches de Sousa Soares, known as Noémia de Sousa who lived between September 20, 1926 and December 4, 2002, was a poet from Mozambique who wrote in the Portuguese language.

She was also known as Vera Micaia. In the early 1950s, de Sousa became involved in the Moçambicanidade movement. Moçambicanidade was the name for a new and revolutionary literature that spread throughout Mozambique during the 1940s and 1950s.

This literary movement was an open platform for the citizens of Mozambique to open dialogue on issues concerning race, class, and politics. In his famous poem called ‘New York’, the great African poet, Leopold Senghor describes an African visitor’s first encounter with the city of concrete and steel, New York.

As the poem begins, the poet shows New York as awe-inspiring but emotionally and morally bankrupt. Through its white inhabitants, New York has “blue metallic eyes and icy smile.

” To the black outsider, the city sky scrapers appear to “strike lightning into the sky.

” The African, who is away presumably from his African village, has had to live “without well water or pasture.

” This increases his sense of nostalgia. Far away from the easy go village full of children, the African has also had to live without a “laugh from a growing child.

” The great city’s dehumanisation is further portrayed through its lack of “smell or sweat” as all the people are hurrying about neatly dressed in their well perfumed bodies!

The outsider is also stunned by the sewer system carrying away human waste, something that is frowned upon in the African village.

The outsider refers to the sewer as the city’s “murky streams” that “carry away hygienic loving / Like rivers . . . with the corpses of babies. ”

To the African, the city is over industrialised and therefore dry and unnatural.

In a different section of the poem, there is praise of Harlem, the black side of the city where one finds black people. Most of them are direct descendants of slaves who were shipped from Africa to America.

The poet thinks this black section carries the warmth of black people and that essentially, it offers a remedy to the emotional bankruptcy of the white side of the city.

The music and arts of the black people in Harlem appears to be what the white side of New York should copy for survival:

“Now is the time of signs and reckoning, New York!

I saw Harlem teeming with sounds and ritual colors

And outrageous smells —

At teatime in the home of the drugstore-deliveryman

I saw the festival of Night begin at the retreat of day. And I proclaim Night more truthful than the day.

It is the pure hour when God brings forth

Harlem, Harlem! Now I’ve seen Harlem, Harlem!”

Finally, the most memorable part of the iconic poem is when the poet actually asks New York to allow itself to learn the warmth and rhythm from black people in order to deal with its stiff and rusty joints:

“New York! I say New York, let black blood flow into your blood.

Let it wash the rust from your steel joints, like an oil of life

Let it give your bridges the curve of hips and supple vines. Now the ancient age returns, unity is restored…”

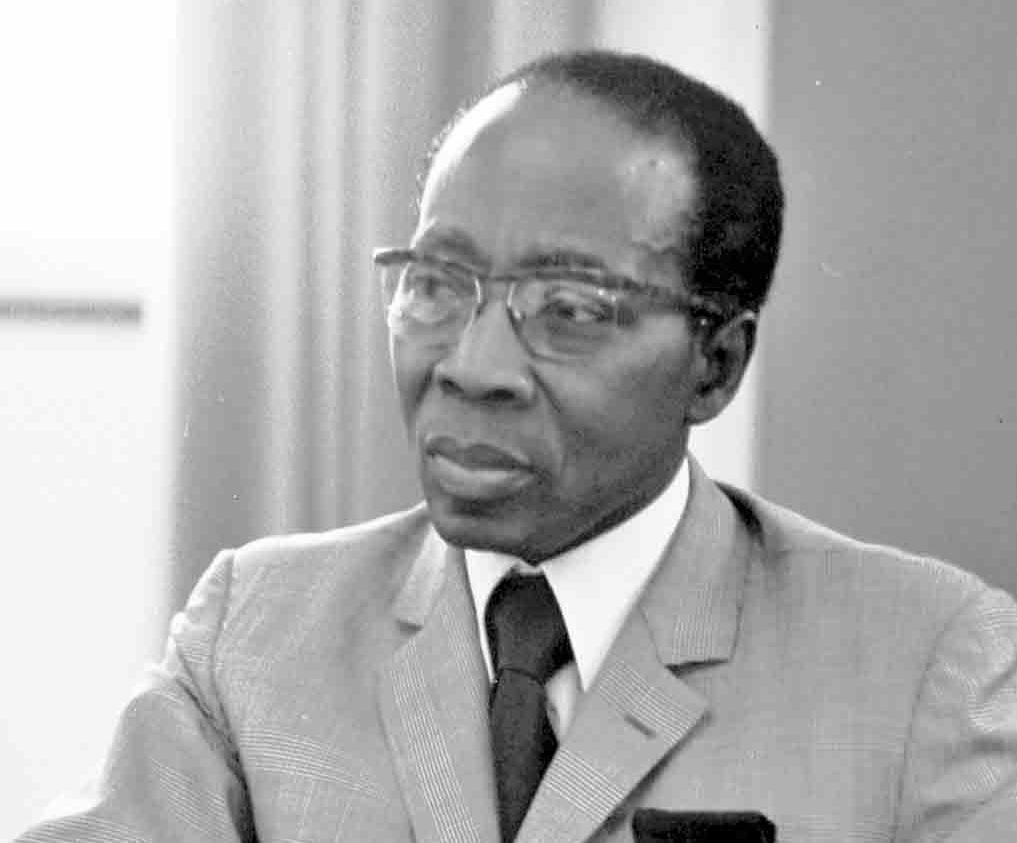

Leopold Senghor is one of the pathfinders of the Negritude movement fashioned out by black students from Franco-phone Africa who met in Paris for their studies in the 1930s.

These were Aime Cesaire from Martnique, Leopold Senghor from Senegal and Leon Damas from Guyana. Eventually, they came up with a kind of poetry that celebrated black beauty, black culture and the beauty of the black personality.

It was an anti-colonial cultural and political movement which sought to reclaim the value of blackness and African culture. Agonstinho Neto’s poem called ‘Kinaxixi’ is based on a square in the city of Luanda, the capital of Angola. The poem is set in colonial days.

The persona sits there and starts to look at fellow black people who also come to sit there and he tries to find essence in such a colonial city, a place built not for their comfort but exploitation:

“And I would see the black faces

of the people going uptown

in no hurry

expressing absence in the

jumbled Kimbundu they conversed in.

The people are in no hurry and they are almost absent. They are here but they are also not here. They belong to this place but the place has been arranged for them by others.

Sitting in this square, the persona sees that the past, the present and the future in a colonial city, do not belong to the colonised. This is not a place that allows these people agency.

It is not a place created in order to allow them to achieve their natural dreams; happiness, food, love and prosperity:

“I would see the tired footsteps

of the servants whose fathers also were servants

looking for love here, glory there, wanting

something more than drunkenness in every

alcohol.

Neither happiness nor hate. ”

The story of Agostinho Neto is almost synonymous with the story of the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) which championed the struggle for Angolan independence and is the ruling party since 1976.

Neto, a qualified medical doctor himself was in and out of prison in the 1960s for his political views and activities. His poems which were “smuggled out of prisons remain the best known of all Angolan poetry.

” They are also said to “form the basis of many popular songs” sang during the struggle for Angolan independence.

They have been translated into many languages including English, Chinese, French, Italian, Romanian, Russian, Serbo-Croat, Spanish and Vietnamese!

Yvonne Vera’s prose is often intense prose poetry.

Without A Name (1994), is the most talked about of all Vera literature. Like Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, Vera’s story is about a woman who travels across society, from one lover to another, in search of love, freedom and fulfilment.

Her innocence is shattered much early in life when she is raped by a man in uniform in colonial Rhodesia. At some point Mazvita leaves behind the countryside to go to Harari, the colonial city.

This is how the prose poetry describes her initial experience:

“It was like that when she arrived in the city. She felt a rare freedom eagerly anticipated.

It moved over her just like that. The buildings were so high that they made her want to crouch or bury herself in the ground, anything but to walk up straight.

She collapsed in a heap on the pavement and watched the cars move past…. Multitude of feet moved by. Harari was pestilence. Feet swished past. The city was unapologetic.

The city was on time. Harari was festive. Roads were four wheeled, black tarred and moving…No one cast her a pitiful glance. She was not there at all.

Her name was only hers; she could change it at any time. She called herself Rosie while she sat there, and laughed inwardly. She called herself Mildred… then Margaret…then Angelina…then Constance…Juliet.

She preferred Juliet…. ”

The irony is she does not realise that the city is the centre of oppression. It is where capitalists are waiting for vulnerable women such as Mazvita, and use them for their own benefit.

Here are thieves that do not only steal people’s valuables but their innocence too. Instead of making Mazvita forget her troubles and memories of rape in the countryside, it makes her remember everything.

In this story, the colonial city is seen as a cultural incinerator. It reduces black humanity to an amorphous heap of rubble, defaced apparitions and sex maniacs.

For example, city men like Joel, turn Mazvita into willing bed-fodder. The African people are warped creations of the colonial city and caricatures of African manhood.

The bubbling life of Harare is predicated on false freedom and excitements. It remains to be seen how, going forward, the young generation of African poets are going to ameliorate the western and colonially oriented western city in Africa.

The obvious challenge is that the city in Africa continues to grow into a monster that does not treat Africans with kid gloves! Just before his death, Marechera said moanfully about Harare: “Ah Harare.

Its mysterious method of living out of a suitcase, living in anonymously cheerless but expensive blocks of flats, living no longer on borrowed time as in the past but on borrowed money, hire purchase, the black market, and the small advances one may rarely extract from the employer’s reluctant clenched fist. Harare, where a scream in the night is the signal for all shutters to come down – it’s none of my business who is murdering who…”

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press