Africa-Press – Mauritius. The COVID-19 global health pandemic has come at a time when the world order was already fragmenting. The circumstances have accelerated Africa’s need to reevaluate its geo-strategic position.

There are lessons both from grappling with humanitarian crises on a continental scale and Africa’s navigation of the dynamics of the Cold War era that ended in 1990.

Many analysts expressed grave concern that the African continent would be unable to manage the impact of the pandemic. While it is premature to draw conclusive evidence, certain African states have provided exemplary models in combatting the crisis.

They have used emerging technologies in innovative ways and developed reliable information channels for public messaging.

Africa’s response has also benefited from the use of established public health and infectious disease systems developed to respond to viruses such as Ebola.

The COVID-19 Africa Watch established an impressive platform that highlights the work of civil society, states, and inter-governmental bodies across the continent.

Setting up the Africa Centre for Disease Control, alongside the African Union, has helped ensure timely and coordinated updates in line with global standards.

Africa’s past handling of pandemics have made its citizens and state officials aware of the means by which addressing such large-scale health challenges can be done through basic public health.

[v] From Addis Ababa to Nairobi to Accra and other capitals in between, travellers usually encounter teams of medical professionals upon arrival.

These health desks at airports serve not only as a means to ensure vaccination papers are in order, but also to monitor symptoms through temperature checks via thermal scanners. As a result, Africa finds itself more prepared than many other parts of the world.

However, most African countries suffer from fragile, resource-poor health systems and deep socio-economic constraints.

These factors have contributed to the complexities of organising a robust response to COVID-19 throughout the continent. All of this comes at a time when global governance systems are being severely tested.

It is inadequate to view the changing global order as a binary competition between the East and the West. The world is more complex, if not multipolar.

To this end, the European Union’s engagement with Africa is underpinned by the rhetoric of equal partnership. It is based on the understanding that Africa is no longer interested in being dependent. EU member states are aware of the geopolitical realities in the continent and are putting forward an EU-Africa strategy.

This is linked to “an EU neighbourhood policy” not only aimed at protecting economic interests, but also preventing illicit migration.

Additionally, individual EU member states are crafting bilateral strategies for Africa. This includes countries like Finland which carries no colonial legacy but understands the strategic importance of Africa for its own future.

More profoundly and drawing from its own historic post-war experience, Germany is undertaking the establishment of a Marshall Plan for Africa.

But whether the scale of this proposal can match even a fraction of the level of investment injected by the United States into Western Europe in the aftermath of the Second World War will determine whether Germany’s grand vision moves from rhetoric to projects on the ground.

To this end, the Cold War has stark lessons on the dangers for Africa of being drawn into disaggregated ideological blocs. Proxy warfare and ideological divisions entangled the continent for decades into a web of intrigue and armed conflict.

The difference between today and the dynamics of the Cold War is that the actors, issues and options are less clear. The rise of nationalistic politics and the demise of democratic systems, is calling into question which models of governance are most convincing, effective and sustainable in Africa.

The current era has unveiled a multiplicity of actors perpetuating conflicts, often tied to raw private and public economic interests that undermine coherence and effectiveness of international peace and security mechanisms.

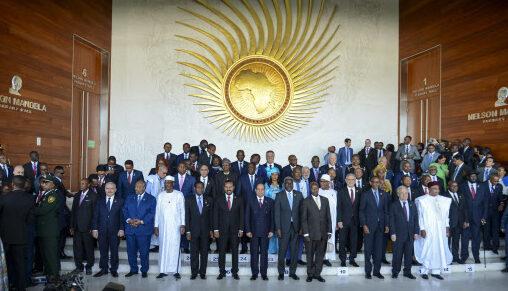

Despite international setbacks, multilateralism both conceptually and organizationally remains relevant in Africa. The African Union has pushed to establish broader normative frameworks.

This can be witnessed through progress toward the free movement of African citizens across the continent and increased interstate cooperation on matters of peace and security.

Next year, the continent starts the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area to boost commerce and economic cooperation within the region.

The African continent must reinforce these multilateral initiatives to strengthen its response to the global health pandemic and position itself within the changing world order.

African leaders need to summon the courage to resolve inter-state disputes and provide a unified approach on peace and security that is anchored on their region’s experience.

For this to be effective, African states must avoid being lured into great power competitions. The continent should pursue the interests of its member states and remain impartial towards disputes between the world’s big powers.

Africa cannot afford to be merely a recipient of policies, passive observer, theatre for proxy warfare, or a continent in which global and sub-regional powers carve out new spheres of influence.

By utilizing its strategic assets and projected interests, Africa has the opportunity to be a global leader in its own right. Doing so means that African states should work as a unified collective without compromising sub-regional specificity nor state sovereignty.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press