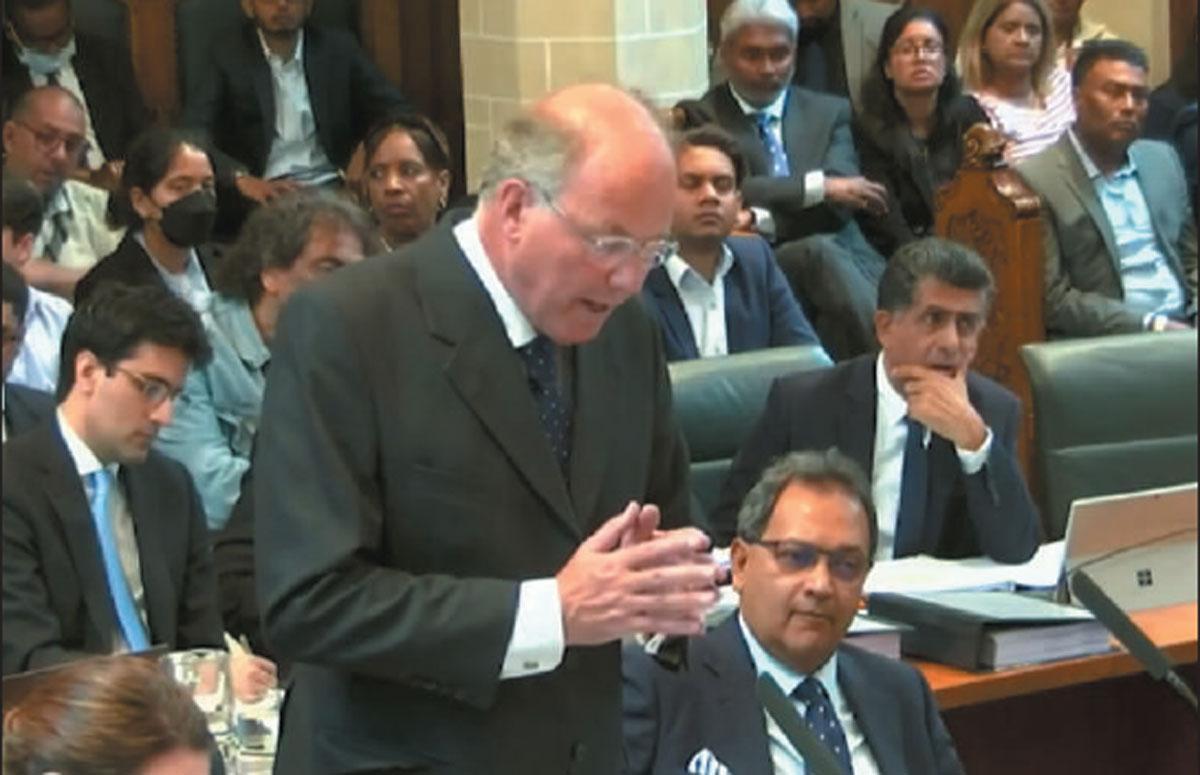

Africa-Press – Mauritius. This Monday 10th of July, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC), composed of Lord Lloyd-Jones, Lord Sales, Lord Hamblen, Lord Stephens and Dame Sue Carr, heard the widely awaited appeal of Suren Dayal’s petition asking to invalidate the election of Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth and running mates Leela Devi Dookun-Luchoomun and Yogida Sawmynaden in constituency No. 8 back in the 2019 election.

The appeal was against the ruling of the Mauritian Supreme Court on August 12, 2022, that had dismissed candidate Dayal’s grounds of appeal on all counts of electoral bribery against the three MSM candidates for having made various campaign promises and generally endeavoured to unduly influence electors of No 8 constituency.

Those promises of pecuniary value included a consequent rise in the Basic Retirement Pension, an allowance to members of the Disciplined forces and an early implementation of the Pay Research Bureau report.

Those promises were made by the PM in the presence of his two 2019 running mates, at a special gathering of elderlies organised by the Ministry of Social Security on the 1st of October, where they were treated with food and beverages, a few days before the National Assembly was dissolved and, as it became clear in those Committee hearings, held in full public view, well before the MSM party/alliance campaign manifesto was made public (23rd of October 2019) and the actual polls were held (6th of November 2019).

To place matters in context, constituency No 8 and another Jugnauth (Ashock, the uncle of Pravind Kumar Jugnauth and front-bencher of the MSM then), were coincidentally involved in the only successful example of a challenge for electoral bribery in Mauritian legal history.

In that particular case, Raj Ringadoo, the unreturned candidate of the Labour-PMSD bloc in the 2005 election, contested the election of outgoing health minister Ashock Jugnauth of the MSM-MMM coalition and won his case both at the Supreme Court and, on appeal, at the Privy Council.

That case certainly hovered in the background of both the SC and the JCPC, as electoral bribery or corruptly influencing electors of a particular constituency is usually difficult to distinguish from the ups and downs of normal electioneering processes, where candidates are likely to advance their cause and spell out campaign pledges of what they intend to do should they be elected and form the next government.

But the circumstances surrounding Ashock Jugnauth’s case and court rulings were notably different, in that he was judged to have firstly misrepresented a Cabinet decision on land for a muslim cemetery to an audience of mostly Muslim electors in constituency No 8 and secondly, entered in a recruitment spree of hundreds of low-wage workers majoritarily from his constituency a few weeks prior to actual polls that were to be held on 3rd July 2005.

In that historical judgement that was upheld later by the Privy Council, the Supreme Court concluded that “the campaign was conducted not so much along the line of government performance but on the basis of ‘donnant donnant’ where votes, individually or collectively, were exchanged for jobs in the civil service”.

It did give the Supreme Court the opportunity to comment and highlight two factors that were likely to distinguish « normal » electioneering pledges and promises from those that might be considered as attempts to exert undue or corrupt influence over elector choices, namely the rather obvious quid-pro-quo of votes for civil service jobs in Ashock Jugnauth’s departments and the highly localised nature of those promises and actions in constituency No 8.

The fact that neither the promises of Civil Service jobs nor land for a muslim cemetery were part of the 2005 MSM-MMM electoral manifesto could have been perceived by both the Supreme Court and the Privy Council as peripheral to the main legal grounds of the Ringadoo case.

Was it necessary in any case for political parties or alliances to have a physical document of reference such as a manifesto, rather than public declarations and pledges made during electoral campaigning that amount to having a similar effect?

One could understand better from the Monday hearings why the Suren Dayal grounds of appeal against the three returned candidates of constituency No 8 faced some uphill legal difficulties at the Supreme Court as the circumstances were different from the Ashock Jugnauth case in as much as promises made by the then PM on 1 October 2019, even though at a wide gathering of elders and old-age pensioners and in the absence of a specific documented manifesto, were construed as part of « normal » electioneering in Mauritius.

For More News And Analysis About Mauritius Follow Africa-Press