Africa-Press – Namibia. IN Basel, Switzerland, the largest Namibia-focused library outside of Namibia marked its fiftieth anniversary last year. Over the years, many Namibian scholars have visited the BAB, worked with its collections and engaged in workshops and exhibitions often also held in Windhoek. The University of Namibia and the National Archives of Namibia have been long-term partners. The ‘Basel Namibia Studies Series’ has become a household name, with many Namibian authors contributing to it.

The BAB, since 1994 part of the Basel-based Carl Schlettwein Foundation, has over the years seen some marked interventions in Namibian knowledge production. How do they relate to current debates on decolonising knowledge development and accessibility?

LIBERATING LIBRARIES In 1971, BAB founder Carl Schlettwein envisaged the transformation of his private Namibiana library in Basel into a publicly accessible library for Namibia.

As is well known, the South African regime in South West Africa at the time had no interest in making knowledge, information and research results accessible to a wider audience. Knowledge – and propaganda – control reigned in not only the apartheid government but also among local libraries and archives.

Schlettwein’s project, joined soon by the formerly Windhoek-based librarian Eckard Strohmeyer in West Germany, attempted to counter such policies by compiling a national bibliography. Before online catalogues and databases, such a bibliography and a national library – none of which existed in Windhoek – were the common way to obtain information on published materials.

As Schlettwein wrote at the time: “As Southwest Africa represents a relatively small field for activity of a library, we could imagine that one special collection would serve the purpose best. Perhaps all present stocks, or at least a major part of it, could be combined in one library?”

Between 1971 and 1979 he and Strohmeyer published the first ever “Namibian National Bibliography” (NNB). The NNB was reviewed critically, with Werner Hillebrecht, Namibia’s foremost bibliographer to be and since the late 1970s building a vast electronic database, Namlit, referring to the NNB as “a real breakthrough in Namibian bibliography … [F]or the first time … a comprehensive coverage of Namibiana … in all respects: of subject, of language, of geographical provenance . … The most important [shortcoming] is a weak coverage of material originating from the liberation movement, UN, and international solidarity”.

Carl Schlettwein took this seriously and by the late 1980s had built a strong collection of published materials issued by the Namibian liberation movement Swapo.

He purposefully collected UN and international solidarity publications only selectively as these were readily available in various libraries in western Europe. In a similar vein he did not collect German colonial literature comprehensively, arguing that there was no need to build yet another German colonial library. The BAB’s strong focus was on any publications from Namibia in any languages – a strategic intervention in Europe and as relevant then as today.

After independence, several libraries were repatriated to Namibia. Discussions with Namibian stakeholders led to the decision to expand the BAB library in Europe and regard the accessibility of Namibian publications in Europe as imperative.

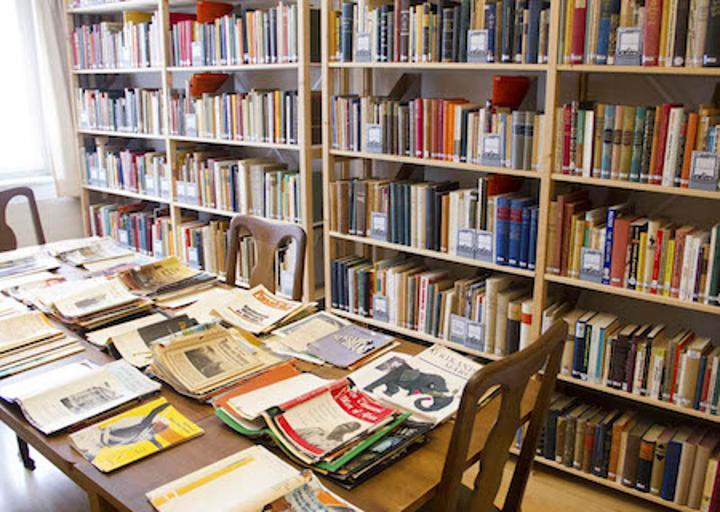

As such, the BAB continues to operate in Europe as a Namibian library ‘in exile’, and it imports from Namibia any published output, any schoolbook, government publication, book, pamphlet and also poster or commercially available film or music CD, irrespective of language or content.

Postcolonial Namibian nationalism continues to provide, it seems, a useful framework at the BAB to ground African studies in Europe to be what it needs to be – studies rooted in African knowledge production. GROWTH AND CHANGE

A look at the keywords of the BAB’s catalogue shows the challenges in this respect. For example, in order to improve our keyword list, much effort was put into representing all Khoisan languages and even very small languages adequately, in consultation with visiting scholars from Namibia.

Keywords particularly relevant to Namibia such as “genocide”, “land reform”, “communal areas” or “forced removals” are included and also gender-responsive language.

Keyword systems remain largely eurocentric and it is obvious that a fundamental rethinking of keywording and classification practices needs to take root.

Namibian authors in the BAB’s publishing house have featured strongly, a first striking volume having been ‘Namibian Poetry in Exile’ (1982/2004) from Namibian poets, edited by Henning Melber.

The ‘Basel Namibia Studies Series’, initially launched in 1997 by P Schlettwein Publishing and now issued by the BAB, strives to emphasise Namibian and regional academic research and thus includes many Namibian authors. Since the BAB’s transformation as the Namibia Resource Centre in 1995, the archival holdings have been vastly expanded.

We do not take collections from Namibia itself but keep an eye on those private collections by researchers or journalists who over time worked in Namibia while being based elsewhere. This way, important paper manuscript and audio-visual (image and sound) collections with reference to Namibia but located in Europe become accessible. Digital copies, at times also originals, have for years been incorporated and as such repatriated to the National Archives of Namibia in Windhoek.

African orality and languages feature prominently in some of these archives, with more being digitised and being made accessible online. Much more remains to be done. DECOLONISING

Over recent years, the BAB has been discussing a digital Namibia repository with Namibian stakeholders. A first concrete step is the “Portal for African Research Collections”, based at the University of Basel library, with the BAB’s Namibia focus implying a strong outreach to Namibian libraries and archives to follow.

From current positions on decolonising knowledge and knowledge production, the BAB’s building projects since the early 1970s were milestones in terms of comprehensiveness, diversity and accessibility. At the same time, decisive decolonial positions such as critical engagements with Western concepts of knowledge framing require more decisive steps.

Digital accessibility is important, but in itself it is not necessarily a decolonial strategy. Decolonial object matters relate to questions such as: “Who speaks in and through library and archival collections” and “on whose terms with which categories?” The engagement of Namibian scholars in Basel seems more relevant than before.

For More News And Analysis About Namibia Follow Africa-Press