Africa-Press – Rwanda. In a wide-ranging conversation, Ambassador Charles Murigande – a mathematician, former minister, educationist, and veteran of Rwanda’s liberation, shares a personal account of Rwanda’s transformation, from the pain of exile to national renewal.

Born in Rwanda but grew up in exile, he reflects on the burden of statelessness and the resolve that led him and many others to join the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF-Inkotanyi). The former RPF Secretary General discusses the power of civilian mobilisation, the moral urgency of reconciliation after the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, and the ongoing effort to sustain Rwanda’s hard-won progress.

Amb. Murigande recounts pivotal moments from his journey and offers insight into the challenges and hopes that continue to shape Rwanda’s future. Excerpts below,

Could you share a brief overview of your personal background – where you were born and your educational journey?

I was born in 1958 in Gashiru, in what is now Nyaruguru District, in southern Rwanda. Shortly after, my parents were forced to flee the country and settle in Burundi as refugees. I was just two years old and grew up in various refugee camps there.

I completed my primary education in those camps. For secondary school, I attended College St. Albert, a school established by refugees to educate their children.

Afterward, I was admitted to the Université du Burundi (formerly Université officielle de Bujumbura), where I studied for two years before receiving a scholarship to continue my studies in Belgium.

There, I earned both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, completing a PhD in mathematics in 1986. Later, I pursued an MBA at the University of Canberra in Australia.

In terms of family, I was the fifth of the surviving children; I’m told five had passed away before I was born. When we left Rwanda, there were five of us, and a sixth sibling was born in exile.

How did growing up in exile shape your worldview and inspire your involvement in the liberation struggle? When did the idea of liberation become a personal calling?

Life as a refugee is filled with hardship. You constantly question your circumstances. At our refugee-run secondary school, for example, we often asked why we could not attend the schools designated for Burundians. Why were we treated as second-class citizens?

When I was in Senior 3, some classmates and I would visit François Rukeba, a renowned patriot who had fought for Rwanda’s independence and later went into exile. He lived in Bujumbura at the time. We would sit with him, ask questions about Rwanda, and discuss how we could reclaim our rights and citizenship.

We felt a deep sense of responsibility. When the Rwandese Alliance for National Unity (RANU) was formed to mobilise refugees for liberation, I joined as a member and became a mobiliser. RANU would eventually evolve into the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF).

Walk us through the formative steps that led to the creation of the Rwanda Patriotic Front and Army (RPF/RPA). How did the RPF/RPA emerge, and how was its vision shaped and supported by the diaspora?

I joined the Rwandese Alliance for National Unity (RANU), formed in 1979 in Nairobi by Rwandan refugees. Many of them had fled instability multiple times, moving from the DR Congo to Uganda, and eventually to Kenya.

They began asking themselves: “How long will we keep fleeing our country, as if we don’t have one?” This reflection led to the creation of RANU, with the goal of addressing the conditions in Rwanda that kept so many in exile.

Mobilisation was slow and cautious. As refugees, political activity was prohibited, and the Rwandan regime was actively spying on them.

Before approaching someone to mobilise them, it was essential to carefully assess their character, relationships, and the potential risk they posed to the movement.

In 1987, during a RANU congress, members evaluated the progress made and the obstacles they faced. Other groups were also emerging, and it became clear that RANU was not broad-based enough.

There was a need for a movement that could bring together people from diverse backgrounds – united by a shared commitment to a minimum political programme.

This eight-point programme became the foundation for a more inclusive movement. It welcomed anyone – communists, capitalists, Christians, non-Christians, so long as they supported the vision of transforming Rwanda into a nation that welcomes all its citizens, offers equal opportunities, and aspires to prosperity.

With this programme and a new method of work, we began broad-based mobilisation, reaching out to Rwandans both in exile and within the country.

For younger generations who only know today’s Rwanda, how did the mobilisation for the struggle begin, and why did it ultimately become necessary to take up arms?

Mobilisation began with building an organisation. Civilians played a crucial role in laying the foundations of the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF-Inkotanyi). Cadres, especially civilians, worked tirelessly to raise awareness among Rwandans about the country’s dire situation and the possibility of change.

This grassroots effort led to recruitment into the armed wing. Initially, many recruits joined Uganda’s National Resistance Army (NRA). But with the launch of the liberation struggle on October 1st, 1990, we formed our own force – the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA).

These cadres were instrumental in producing the soldiers who filled the ranks of the RPA. But their contribution went beyond recruitment.

The struggle also demanded food, clothing, medical care, and weapons. Full-time cadres, many of whom gave up jobs or chose not to seek employment after graduation, committed themselves fully to securing the resources needed to sustain the fight.

The military efforts of the RPA are well documented, but what role did civilians and cadres behind the scenes, especially in mobilisation and organisation abroad play?

Another important aspect was making the international community understand the cause the RPF was fighting for. Some cadres took on the responsibility of lobbying and sensitising global audiences to help them see why people had taken up arms to fight for their liberation. This work was done by civilian cadres.

They played a crucial role. If the military had started fighting without the support of civilian cadres and the broader population, they would not have made much progress.

Without international understanding and support, the entire world could have turned against the movement, severely limiting its impact.

There was a collective and complementary effort between the military and civilian cadres. Many people made profound sacrifices. I knew couples—husband and wife, who left their children with grandparents to join the struggle, not knowing if they would survive.

How difficult was it to build support, manage logistics, and engage the international community in recognising the legitimacy and urgency of the Liberation cause?

Mobilising Rwandans was not easy. We had spent nearly 30 years in exile, and many had lost hope of ever returning. Some told us, “You’re just dreaming. Why not focus on getting citizenship where you are? And if you can’t, just accept it and move on.” They didn’t believe the effort would lead anywhere.

Even inside Rwanda, and among refugees themselves, people would say: “The government is too strong. How can you fight an established regime with solid ties to powerful countries like France and Belgium?”

The challenge with the international community was similar. They asked: “Who are you to think you can fight and change, or even overthrow – an established government?” But we kept insisting: “We have a just cause. It may seem weak now but it is right, and that strength will grow.”

Eventually, some in the international community began to understand. We developed a network of allies who helped articulate our point of view, and over time, the cause gained recognition.

During the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, how did you navigate the challenge of making the international community understand the unfolding tragedy? What was your personal reaction to the global response?

Although the genocide was clearly being prepared, openly and in plain sight – the international community did not believe it would happen on the scale it did. Either they failed to fully grasp the reality, or worse, they understood and simply did not care.

And once it began, it became evident that those being killed were not seen as having the same value as people in other parts of the world – at least not enough to justify the investment of human, military, financial, or diplomatic resources to save them.

There were many contributing factors. Rwanda was a small country without oil, gas, or diamonds – resources the international community tends to prioritise. And at least one influential country, France – was closely aligned with the regime and determined to protect it.

We felt hopeless, helpless, and deeply angry. How could the international community, bound by the 1948 Genocide Convention, simply do nothing? It wasn’t due to ignorance, they had all the information and saw the warning signs.

Even when the genocide began, confirming those warnings, they chose not to act. In fact, by withdrawing existing peacekeeping forces, they helped create an enabling environment for the atrocities to unfold.

Over the past 31 years, you’ve served in various leadership roles. How would you describe Rwanda’s journey of rebuilding, reconciliation, and unity since the end of the genocide?

The genocide and the war to stop it left Rwanda utterly devastated. In just three months, we lost one million people, about 14 per cent of our 7.5 million population.

The country was left with hundreds of thousands of orphans, widows, and widowers. Social and economic systems collapsed: banks were looted, the economy halted, and administration at every level ceased to function.

Survivors were either internally displaced or fled as refugees to neighbouring countries. At one point, there were nearly 40 camps for the internally displaced.

Rwanda was not just starting from zero – it was starting from far below zero. Imagine governing a remote, unadministered area; even that would have been better than the ruins we inherited. Our people were traumatised, many having witnessed or been forced into horrific violence against neighbours, teachers, and family.

The world believed Rwanda would become a failed state, trapped in cycles of revenge and unending conflict. But one of the most pivotal decisions made by the RPF-Inkotanyi was to reject governing alone.

Although we had defeated the genocidal regime and had the right to rule, doing so would have contradicted our mission to rebuild national unity.

Instead, we formed a Government of National Unity, inviting all political groups not involved in the genocide to participate.

We wanted every Rwandan to feel represented and safe – that no decision from Urugwiro Village would ever harm them. This inclusive approach was crucial in rebuilding trust and laying the groundwork for reconciliation.

The second major decision we made was to strongly discourage revenge. Despite the deep personal losses many soldiers had suffered, retaliation was forbidden.

Those who disobeyed were court-martialed or even executed. We insisted on justice through lawful means, which helped prevent Rwanda from descending further into chaos.

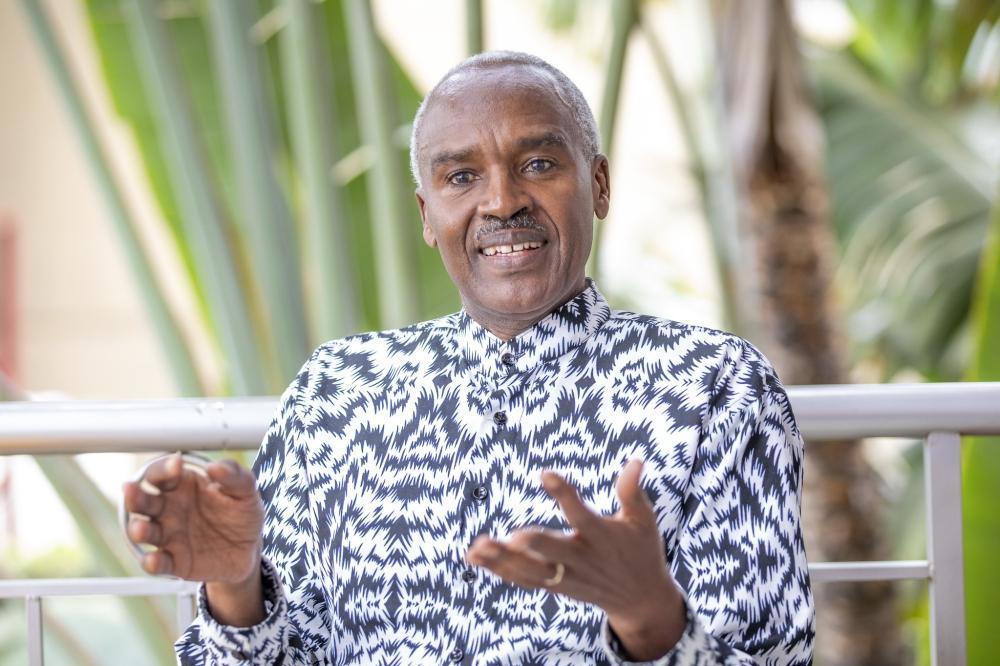

Ambassador Charles Murigande former minister, during the interview with The New Times in Kigali on June 18. PHOTOS BY Emmanuel Dushimimana

The third key decision involved refugees. Millions had fled the country, and while it was tempting to reject their return, especially after years in exile – doing so would have contradicted the RPF’s core mission of rebuilding national unity. Unity required the return of all Rwandans.

Thus, the Government of National Unity focused on restoring order, stability, and enabling refugees to return safely. We worked with UNHCR to create a “come and see, go and tell” approach – allowing people to visit Rwanda without losing refugee status.

Unfortunately, these efforts were undermined by ex-FAR and Interahamwe militias who controlled the camps through fear and violence, spreading lies that returning Hutus would be killed.

When these groups began infiltrating Rwanda, we had no choice but to act. Liberating our citizens from those camps was essential for reconciliation and unity.

Once they returned, we launched the Urugwiro Dialogue, a nationwide reflection on our past, our shared history, and our path forward toward a united Rwanda.

Since then, Rwanda has seen remarkable progress. Infrastructure has grown – electricity access rose from 3 per cent in 1994 to 75 per cent today; phone access now reaches 95 per cent of the population. We have modern roads, buildings, and airports under construction.

More profound has been our social progress. The genocide was carried out by Rwandans against Rwandans – yet today, we live side by side.

Children study, live, and even sleep in the same dorms. Inter-ethnic marriages are now common. Reconciliation and social cohesion have advanced significantly.

But we must remain vigilant. Genocidal ideology persists, especially among those abroad who still harbour hatred and pass it to their children. Outside Rwanda, they can promote these views without consequences, posing an ongoing threat.

To protect our progress, we must strengthen unity through initiatives like Ndi Umunyarwanda, which reminds every citizen that their primary identity is Rwandan – not Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa.

We must also engage youth in the diaspora to help them embrace their Rwandan identity and contribute to the country’s future. This work must continue with unwavering commitment.

Liberation doesn’t end with war. In your view, what social, economic, or ideological areas should Rwandans focus on to sustain and deepen it?

We must continue building a Rwanda where every citizen enjoys equal rights and protection under the law. This requires a justice system led by people of integrity – free from all forms of corruption, whether financial or rooted in favouritism based on appearance, background, or personal connections.

Justice must be impartial and present in every office, public or private – not just in courts. As scripture teaches, justice is the foundation of a secure and prosperous nation. We must keep striving for this kind of justice.

Poverty remains a key challenge. Though progress has been made, it has not been fast or widespread enough. Poverty makes people vulnerable to manipulation, and so economic transformation must remain a top priority – creating and fairly distributing wealth to uplift every Rwandan.

As Pan-Africans, we must also redefine our relationships with other nations, especially within Africa – engaging with the world as sovereign equals. We must move beyond the legacy of colonial influence and reclaim full agency over our destiny.

One of President Kagame’s greatest achievements has been restoring the dignity of Rwandans – teaching us that we are no less than anyone else in the world. That belief in our worth has empowered us to dream, innovate, and rebuild.

His legacy is the dignity he instilled in us – a dignity that fuels transformation and must be preserved and passed down. It is this self-worth, rooted in our identity and value before God that will sustain and advance Rwanda’s progress for generations to come.

How have civilian contributions shaped Rwanda’s path since liberation, and what message would you share with young Rwandans unfamiliar with this history?

I urge young Rwandans to live for others, ready to sacrifice and driven to positively impact the lives of all Rwandans, including themselves and their families. They should always ask: How does what I’m doing transform this country for the better?

They must remember that Rwanda is judged by character, not ethnicity or religion, because young people before them sacrificed their lives for this freedom. Many left school to fight and died, but their cause triumphed.

Now, the youth must protect and build on these achievements by preserving their dignity – avoiding drugs, alcoholism, and immorality, and focusing on improving themselves, their families, and the nation.

Rwanda’s future is in their hands: they have the power either to destroy or to prosper this country.

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press