Africa-Press – Rwanda. On a quiet Saturday evening in Gishushu, just a few kilometers from the bustling Kisimenti, the sun sets over the hills of Kicukiro. In his studio, Samuel Daddy Ishimwe gathers his brushes, paints, and canvas.

He puts on his painting apron, turns on a mellow R&B and pop playlist, and begins his daily craft: visual art. No corner office, no suit and tie, just creativity, color, and a strategy to sell.

That’s the foundation of a visual art business.

Compared to other branches of the creative industry, visual art remains relatively underexplored. Yet, the business continues to grow steadily. One of its key pillars is the role of art galleries, which provide more than just walls to display work.

They offer exposure, creative freedom, and access to a wider clientele through exhibitions and showcases.

Art isn’t just aesthetics, it’s an investment

Walk into any gallery or art exhibition in Rwanda, and it’s not unusual to find pieces priced at $2,000 or more. To some, that may seem excessive. But to the artists, those figures barely reflect the time, skill, materials, and emotional investment behind each piece.

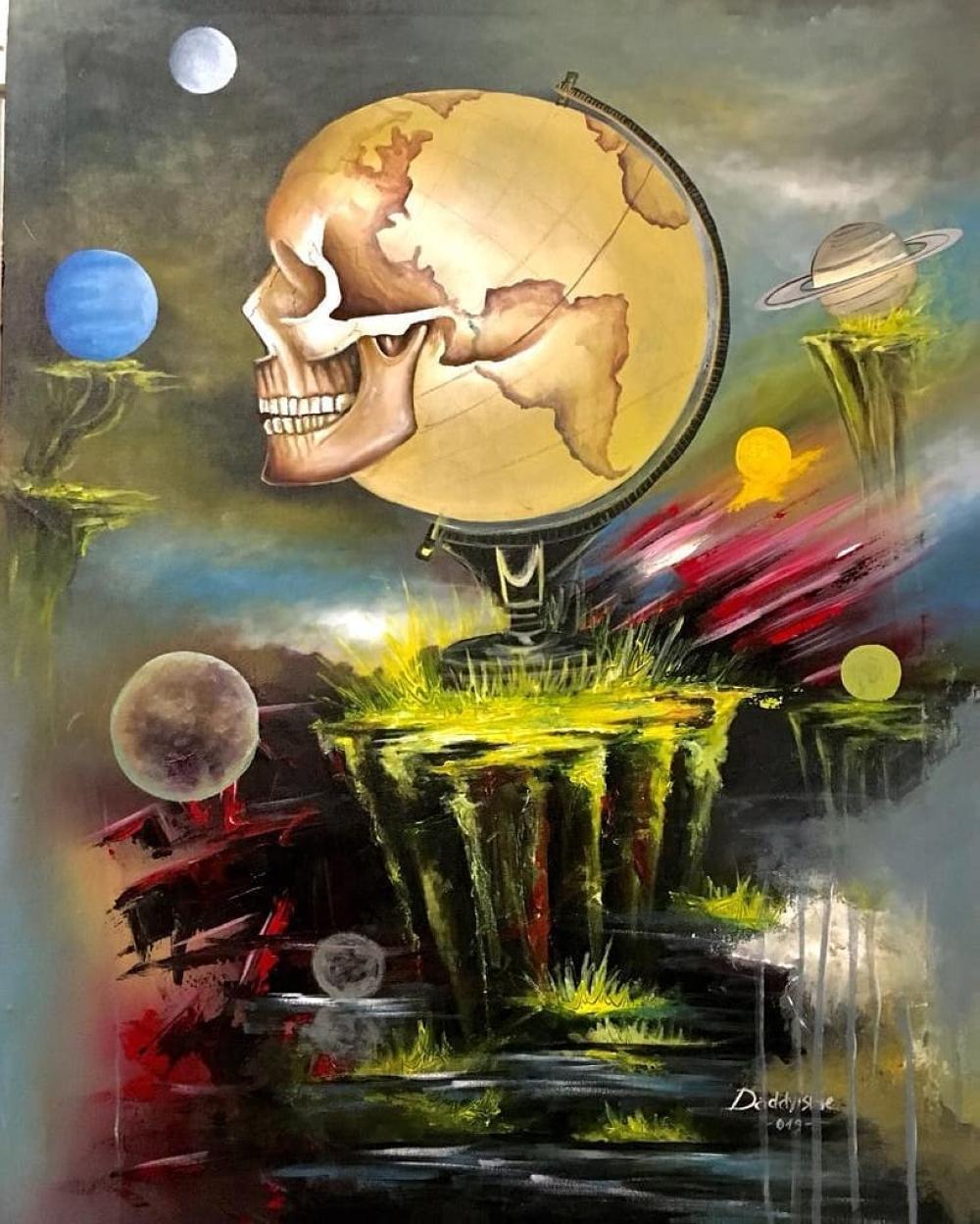

Samuel Daddy Ishimwe, also known as Dadysme, is a visual and multidisciplinary artist who runs Envision Rwanda gallery. During a visit to his workshop, he was working on a conservation-themed portrait, one he said brought him significant income, though he kept the exact amount private.

Like many artists, Ishimwe pairs his creative process with music, which he says grounds him in inspiration and sharpens his focus.

“Creating a piece is like giving birth,” he said. “Selling it sometimes feels like losing a part of yourself. That’s why galleries are essential, they remind us to also think about the business side of art.”

Among his works is a piece titled Black Monalisa, which he spent over a month completing, the longest he’s ever worked on a single artwork. It’s not for sale.

“That one is priceless. I look at it for inspiration. I can’t imagine parting with it, no amount would feel worth it,” he said.

Platforms, partners

To avoid the high costs of working independently or from home, many artists choose to collaborate with galleries. These partnerships offer exposure, logistical support, and financial opportunities.

According to Ishimwe, artists and galleries often profit through partnerships with hotels, government agencies (especially for diplomatic gifts), and art residencies. Exhibitions remain the most consistent source of income.

While most residencies take place abroad, they are increasingly being established in Rwanda. Social media also plays a critical role in marketing and sales.

Artists usually enter agreements with galleries to showcase their work. When a piece is sold, profits are split according to negotiated percentages, which account for taxes and service fees.

“Every piece must tell a story,” Ishimwe said. “Whether commissioned or created from personal inspiration, storytelling connects the work to buyers. The most memorable pieces are those that resonate emotionally.”

Pricing is generally set by the artist and considers factors like materials (often imported), size, time spent, and creative complexity. Artists and gallery owners collaborate to strike a balance between fair pricing and commercial appeal.

“If the price is too low, we lose money. If it’s too high, we lose clients,” Ishimwe explained. “Some buyers, even if they can’t afford a piece, will commission something within their budget, which often leads to long-term relationships and recurring work.”

While Rwandans are gradually warming up to collecting art, Ishimwe notes that most of his clients are tourists, many drawn by the Visit Rwanda campaign.

A growing market

Aime Sandrine Usanase, known professionally as Sachala, is a ceramics and sculpture artist based at Masaka Incubation Centre, where she runs a gallery and workshop.

A graduate of the Nyundo School of Art and Music, she specializes in three-dimensional works displayed in various galleries across Kigali. She says this visibility has helped expand her reach and income.

“When I started, it was difficult,” she recalled. “You have to stand out and build a client base. But with consistency, the returns come.”

Her income has grown steadily. She has sold pieces for as much as Rwf500,000 and recently created background art for THIS and THAT, a popular Rwandan podcast duo.

Usanase attributes her success to consistency, uniqueness, and resilience.

In addition to selling individual pieces, she often receives commissioned projects from galleries. These typically include an upfront creative fee and a profit-sharing model upon sale.

“Some galleries come with specific projects,” she said. “They pay for the creation, and when it sells, we split the profits. It helps keep cash flowing and the work visible.”

The road ahead

As Rwanda’s visual art scene continues to develop, both artists and gallery owners are optimistic. Jean d’Amour Imanishimwe, founder of Live on Art studio, believes that the next step is building infrastructure for artist representation.

“Having agents or managers helps artists access bigger markets,” he said. “The challenge is that many people still don’t understand how the system works or why it’s valuable.”

For most artists, the visual art business is both professional and deeply personal. It requires adapting to changing markets while staying true to their creative identity.

“There’s real money in visual art,” Usanase said. “But you have to chase it. The beginning is tough, but once it starts coming in, it’s worth it.”

Masaka Incubation Centre, where Aime Sandrine Usanase runs a gallery and workshop

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press