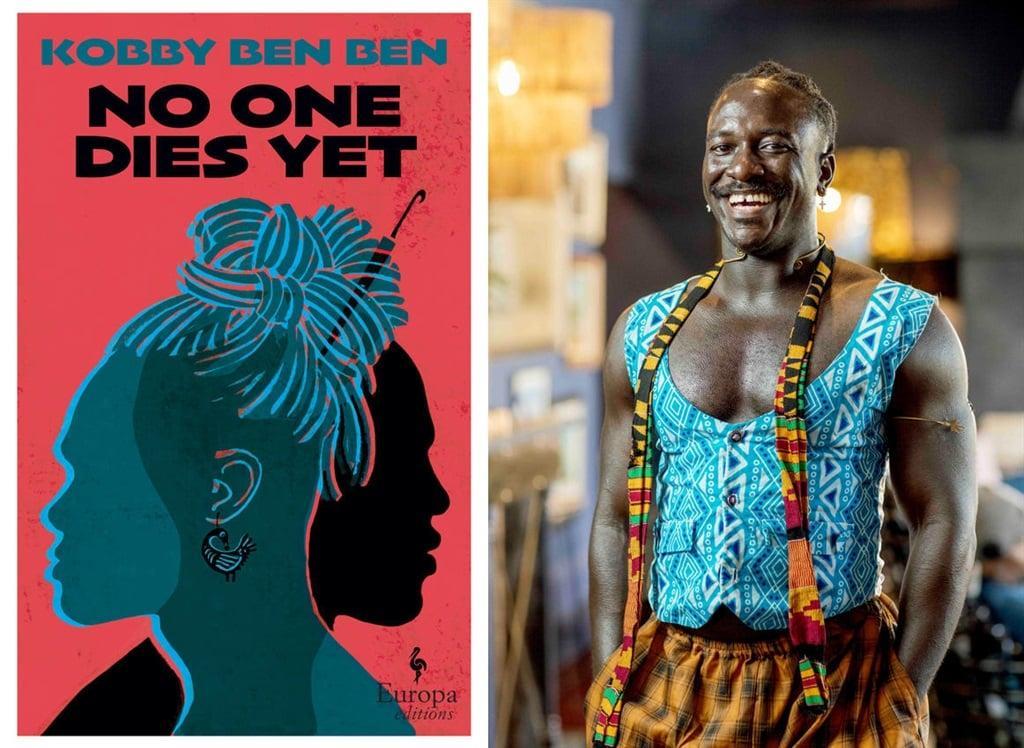

Africa-Press – Seychelles. INTERVIEW: Kobby Ben Ben author of No One Dies Yet (Europa Editions)

Kobby Ben Ben stood out from his very first appearance at the Franschhoek Literary Festival. The bright red leopard-print dungarees he wore to the welcoming event were followed by a series of unusual outfits that had some festivalgoers wondering if he had a secret wardrobe department behind the scenes.

Ben Ben was a hit on stage, especially at the panel on writing about sex, where he had the audience in stitches. He was at the fest to talk about his first novel, No One Dies Yet, which has some of the extravagance seen in his outfits. It’s a wild ride in several voices, a murder mystery and a piece of social commentary written moreover from a queer perspective, which we don’t get enough of in writing from Africa.

The Ghanaian government declared 2019 the “Year of Return”, during which African Americans could visit the country, explore their African heritage there and learn about slavery – it was the 400th anniversary of the start of the Atlantic slave trade. They could also buy property and access other services at a discount.

In 2019, then, three black American gay men arrive in Ghana for the Year of Return festivities. They acquire two guides, Nana, a conservative Christian who’s being manipulated by his pastor, and Kobby, a book reviewer and reporter obsessed with the serial killer apparently stalking the streets of Accra. Kobby is also a queer man living in the strange interstices of the closet in Ghana. Most of the narrative of No One Dies Yet is told from the alternating and contrasting perspectives of Nana and Kobby.

Christian Nana begins to see the sophisticated, gay Kobby as an avatar of Ananse, the trickster figure of Ghanaian myth, and it’s hard not to see Kobby-the-author as a trickster too, so twisty and layered and complex is his overflowing novel. Ben Ben, already famous as a #Bookstagram reviewer of African fiction, brings his literary sensibility into full flower here. Blackness and queerness intersect in troubling ways, yet the play with language is exuberant. There can’t be many other African novels like No One Dies Yet – and it comes out just as Ghana considers an anti-LGBTQIA+ law.

I spoke to Ben Ben in Johannesburg after the Franschhoek fest was over, but while he was still running between writing workshops and the like. He was reasonably modestly dressed.

“African Americans read this novel, and most of them don’t like Kobby,” he says, “because he has this neocolonial critique, and they’re like, ‘Oh my God, this is not how we act in Ghana.’ But Ghanaians read it, and they’re like, ‘Okay, this is exactly how you act.’

“African Americans have access to this returnee loan, I think it’s called, and another called a resettlement loan for African Americans. They can have access to loans for apartments and houses in Ghana without collateral, that’s how wild it is.

“During the Year of Return, it felt like the country was so full. There was traffic everywhere. Inflation everywhere because people realised that African Americans were in town, and prices started going up. Ordinary Ghanaians could not afford it.

“I think it’s just recently that people are getting into a critique of the Year of Return and how it impacted the local economy. It was one of the most successful tourism initiatives on the whole continent. You expected us to have all that income, but then Covid came, and we faced the economic crash the whole world was going through. You wonder where are all the monies, where are all the opportunities promised in the Year of Return. What happened to all those things?

“Beyond making oppression just a race thing, this book goes beyond that and says that it’s a social thing. It’s who has more money, who has a lot more economic opportunities. It’s a class thing. Neocolonialism affects the country. That’s exactly what I wanted to put across. It’s a commentary on the Year of Return.”

And yet, he says, “People to whom the social issues in this book would matter are telling people not to read a book like this because there are gay sex scenes in it. But I’m someone who likes dealing with multiple issues. For me, there’s no central narrative. There might not be one big central theme around which everything revolves.

“When I read queer fiction, I often feel there are other things that are missing. I just feel it’s not a good representation of life. You should read a novel and feel like you’re reading the entirety of something.

“I feel like the Year of Return silenced queer voices. There are so many queer voices. Black American writers who came to Ghana during the Year of Return have written about how their blackness was recognised, but their queerness was missing.”

He asks if I found the opening chapters, where it’s not clear who’s telling the story, confusing. I said I was aware he was playing around with point of view and different narrative voices. In that respect, I thought it a productive confusion. I compared it to Damon Galgut’s endlessly shifting point of view in The Promise.

“Sometimes I have these reader interactions and people say, ‘Oh my God, I would have loved it if you had explained certain things more. It’s social commentary, but I’m also writing a thriller. I love thrillers. So, there’s little room to explain. You need to keep the plot moving.”

“I didn’t intend to write something descriptive. I’m also very coded in my writing. It’s the kind of book you’d have to read over again. When you go back, you have a third perspective. It’s Nana’s, Kobby’s, and the reader’s narrative where the reader gets to sort the truth from the lies.

“The entire book was actually supposed to be narrated by Nana, but as I was writing it, I just didn’t like this Nana guy and I wanted another narrator that could compete with him. When I meet people and they like Nana more than Kobby, I know the kind of reader they are.”

Reading the novel as a whole, once it was written, he says, “I was like, ‘Oh my God, what have I done?’ There are even scenes in this book, the slavery sections, that I wrote once and never went back to it. That section where they were going into the [slave-trading] castle, I just could not read that part again because it was so harrowing.”

Of a later scene with Kobby, he says, “I did not intend it to be like something out of a horror novel, but it just happened that way, and I went with it.

“More than the story, I think the issues matter to me. I wanted people to find something propulsive about the narrative, but this is not of greater importance to me than the themes of queerness, colonisation, neocolonisation and racism. What matters is the issues.”

As for the ending – or endings, plural – of No One Dies Yet, he says, “I wanted to actually open it up for interpretation. There’s an epigram before Part III [in the novel] that says a good ending should be open for interpretation. Readers should wonder what happened back there. I kind of like how everything is deranged, and you have to figure it out.”

For More News And Analysis About Seychelles Follow Africa-Press