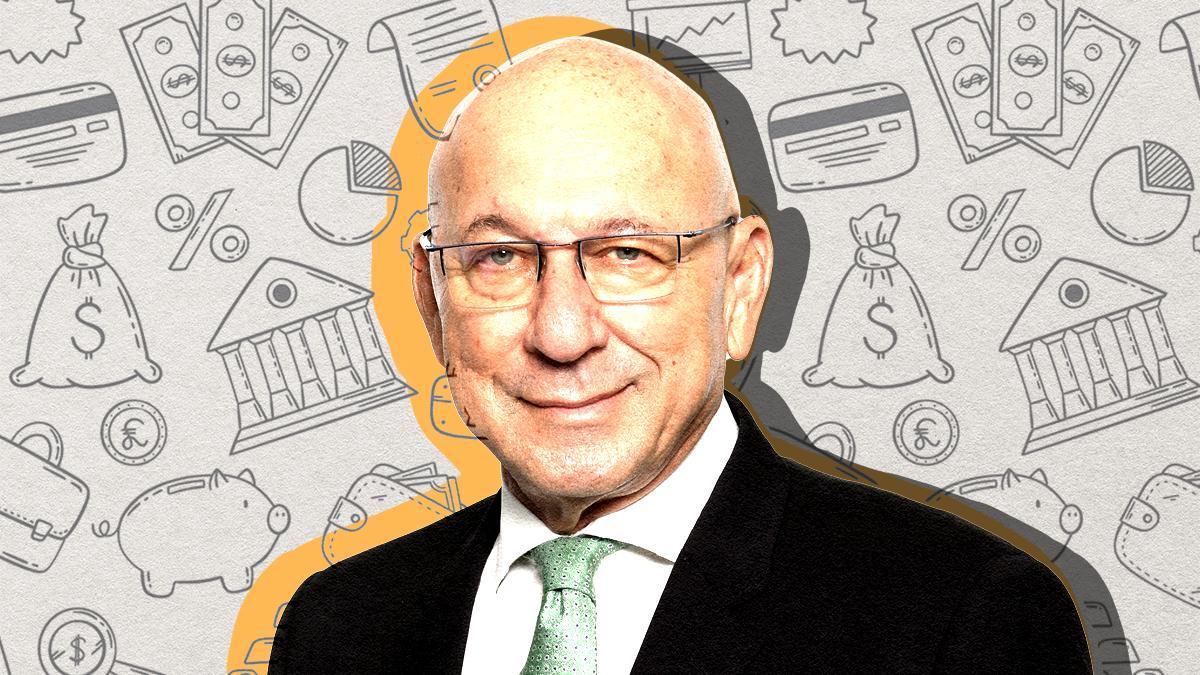

Africa-Press – South-Africa. The ANC’s decision to appoint Trevor Manuel as Finance Minister in 1996 and its willingness to keep him in that position until 2009 saved South Africa from bankruptcy.

It also resulted in the country’s economy growing at a rate it has never seen since, with an average annual growth rate of over 3%.

Employment also soared throughout the mid-2000s, with South Africa’s economy creating around 500,000 jobs every year.

While some of the country’s economic growth was due to a commodity boom, driven by soaring Chinese demand, Manuel’s decision to use the additional tax revenue this created to pay down debt improved South Africa’s credit rating and saw investment flood into the country.

Manuel’s work as Trade Minister is also often overlooked. During his tenure, he took a department whose sole goal during Apartheid was to stifle competition and made it the vanguard of a liberal market economy.

Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings said Manuel’s role is often overlooked by commentators and even the man himself.

“Ahead of the 1994 election, South Africa was in serious economic and financial trouble. In the three years before the election, the country had experienced a prolonged recession,” Lings said.

“Then the ANC did something brilliant. They appointed Trevor Manuel as Finance Minister. I don’t think he knew he was brilliant, but he ended up there and did remarkable things for this country.”

The ANC did far better in restoring economic stability and improving living standards than it was given credit for.

South Africa avoided bankruptcy, arrested its decline, and the economy began to grow with far greater private participation than before.

“The economy took off. It took a couple of years to gain momentum, but then it did really well. In 2008, South Africa’s ten-year average annual growth rate was 4%,” Lings said.

“We have achieved it. It is not impossible. We have hit 4% GDP growth, and the economy has created more than 500,000 jobs a year, with government debt being reduced to 26% of GDP.”

South Africa’s credit rating greatly improved to an A rating from Moody’s, and foreign investment flooded into the country.

While some point to the commodity boom and the additional growth and tax revenue this provided, Lings explained that it was still a brilliant decision for Manuel to use it the way he did.

“Manuel, because of that growth, was collecting lots of tax revenue and generating budget surpluses. What did he do with the extra money? He paid down the country’s debt. He put us in a really good position,” Lings said.

“We were reducing our debt burden and accelerating economic growth. Besides all the other benefits of employment and growing revenue, this was exceptional for South Africa.”

Manuel in government

Manuel, trained as a construction technician, was far from an economics scholar, with liberation politics proving more interesting.

After being initially attracted to the Black Consciousness Movement, he travelled to Botswana in 1979 to join the ANC in exile. The party sent him back to Cape Town to lead its resistance in the province through the United Democratic Front (UDF).

Due to his organisational skills, Manuel quickly rose through the ranks. In 1983, he became the regional secretary of the UDF and a member of its national executive.

Manuel first established his economic prowess as head of the ANC’s internal Department of Economic Planning during the negotiations to end Apartheid from 1991 to 1994.

Only becoming a formally elected party official in 1991, Manuel enjoyed a rapid rise through the ANC’s ranks to work as the head of its Department of Economic Planning.

Upon Mandela’s election victory in 1994, Manuel was appointed as South Africa’s first Minister of Trade and Industry in the democratic era.

During his short time as Trade Minister, Manuel championed South Africa’s economic liberalisation, pushing for the government to embrace free market principles.

This ensured he was sharply criticised by the ANC’s fellow members of the Tripartite Alliance – the Communist Party and COSATU – as a neoliberal. Others described Manuel as a pragmatist.

At the time, Manuel said his priorities would be “to open up our domestic market to international competition”, thus reversing the isolation of the Apartheid era.

After just two years, Mandela saw fit to appoint Manuel to the position of Finance Minister, with the country’s financial health deteriorating significantly.

Manuel was instrumental in shifting the ANC’s economic policy towards that of the market-friendly Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy.

This marked a shift away from the state-centric economic policy of prior years and a break from the ANC’s left-leaning tendencies.

Sharply criticised by trade unions, Manuel pushed GEAR through. The policy framework explicitly targeted reducing the budget deficit to 3%, eliminating tariffs as far as possible and capping the growth of the public sector wage bill.

Economic growth surged to an average annual rate of 4.1% during the Mbeki administration. Under Manuel, the government recorded its first-ever budget surplus in the 2006/2007 financial year, and debt declined as a share of GDP to 26%.

Manuel, who was long regarded as a pragmatist, said in 2013 that he still had little technical knowledge of economics.

“But, I knew that if I set this thing up where people can come with the numbers, and I ask the questions based on life experience and understanding and broad political objectives, then it will work,” he said.

Government after Manuel

For evidence of just how well Manuel did as Finance Minister, Lings pointed to the deterioration of the government’s financial health after he left office.

“Something changed, right? They got rid of Trevor Manuel, and there was a leadership change within the Presidency and the National Treasury,” Lings said.

“Now we find the average annual growth rate is less than 1% over the past decade, government debt as a share of GDP is over 75%, and we are paying R1.2 billion a day to service the state’s debt.”

After Manuel left office, government spending skyrocketed without much benefit to economic growth, as much of it was consumption-based and not focused on enhancing the economy’s productivity.

In 2008/09, gross loan debt amounted to R627 billion or 26% of GDP, with net loan debt at R526 billion or 21.8% of GDP.

The most recent government Budget shows that its gross loan debt was R5.7 trillion, or 76.1% of GDP. This comes at a time when the country’s economy has averaged an annual growth rate of 0.8% for the past decade.

Global credit ratings agencies took note of this decline in South Africa’s financial health. The big three, S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch, placed the country in sub-investment grade, also known as junk status.

Being placed into junk status prohibits many global pension funds and investment schemes from investing in South African assets, as they are considered ‘below investment grade’.

This resulted in significant outflows from South African assets over the past few years, significantly weakening the rand and further limiting economic growth.

In turn, this creates a vicious cycle where declining investment further weakens economic growth, negatively impacting the government’s finances and increasing the risk of investing in the country.

South Africa has been in this cycle for the past 15 years, with the government running its last budget surplus in the 2007/08 financial year. Since then, it has consistently run deficits while economic growth has slowed.

This pattern is evident in the two graphs below, which illustrate the relationship between economic growth and unemployment, as well as the relationship between growth and the state’s budget balance and government debt.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press