Africa-Press – South-Africa. Parliament has become a distraction of the delivery of the State of the Nation Address. Mashupye Maserumule examines whether it should continue to be used as the platform for delivery.

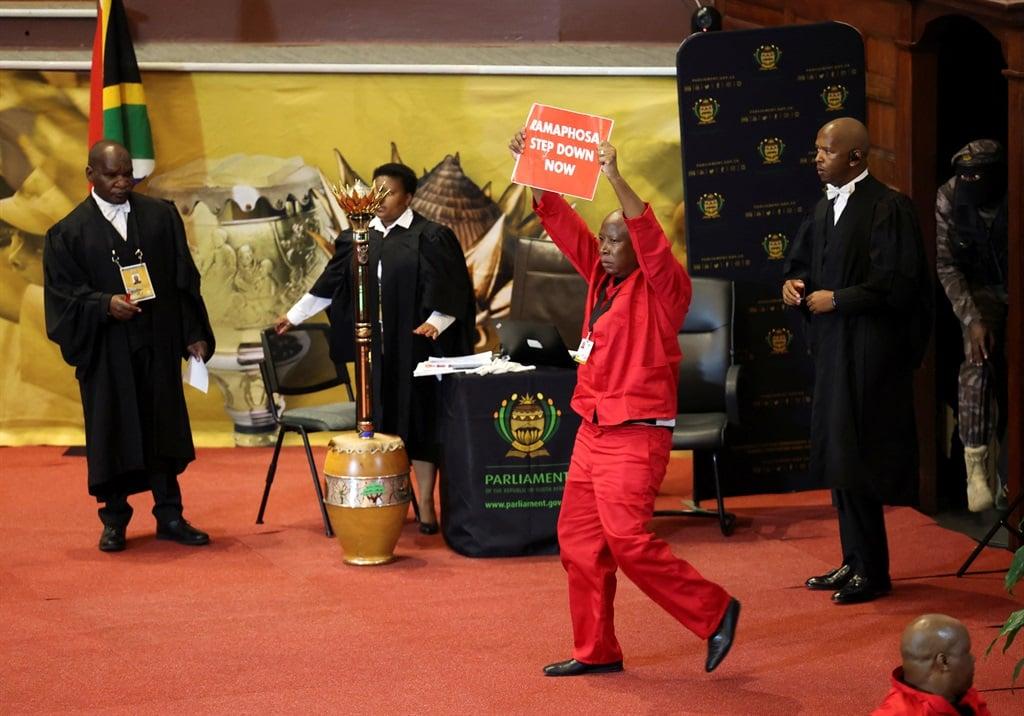

Every February, the sitting President delivers the State of the Nation Address (SONA) in Parliament to showcase government’s achievements, point out where the challenges are, and articulate policy choices to overcome them. The address is debated by the political parties in Parliament. However, in recent years, the address has been marred by chaos from the opposition benches. This is increasingly becoming a trend and is worrisome. It makes one wonder if Parliament should continue to be a platform for SONA.

In the United States, Thomas Jefferson, who had been its third president, dispensed with in person-delivery of the state of the Union Address in the House of Congress, which its founding president George Washington had introduced in 1790. However, the reasons for abandoning it was not interruptions of its delivery by a rowdy chamber, but that Jefferson felt this practice was more of a royal pronouncement that did not show how government worked.

Instead of in-person delivery of the address, a letter was sent to members of the legislative arm of the Union to get a sense of the president’s policy push.

In-person address makes a return

The 28th president of the United States, Thomas Woodrow Wilson returned to the convention of in-person address in 1913. To paraphrase University of New Orleans professor emeritus’ Carol Gelderman, speeches have become “the core of modern presidency”.

However, in South Africa, the histrionics that often plays out during SONA becomes the subject for debate in society of what happened in Parliament during the address rather than the address itself. This belies the very purpose of Parliament as the representative of the people and “a national forum for public consideration of issues”.

Should the in-person delivery of the address in Parliament be ditched for the president to only submit a written report to Parliament about the state of the nation – as the Americans did at some point? The answer is no, but the question about the Parliament as the platform for the SONA cannot be overlooked.

Lately during this address, parties in Parliament jostle for the optics of the moment to amplify their political presence. This is because the event is organised as an elite state affair. All the stops are pulled to bring all organs of the state together to Parliament.

Former presidents, the governor of the Reserve Bank, heads of the institutions that support constitutional democracy, ambassadors and diplomats are invited as guests of Parliament for the event.

But why are the ordinary citizens in whose name the address only allowed on the periphery? This is because of the electoral system of allocating seats in Parliament. It gives even those parties with paltry electoral bases the legitimacy to intercede in the president’s address. But this conflates multiparty democracy with the stealth of stealing the moment for political opportunism. The event’s aesthetic is much a distraction as the politics of its histrionics.

Isn’t time to dispense with the excesses of the event, including its frills that, in any case, are colonial heritage? More troubling is that the event has increasingly become a moment to lay bare societal fissures. But, what can be done to ensure that the address is understood beyond political partisanship, where citizens would have a voice, including in the debate about it, not just parties in Parliament?

For some, the answer to this question is not possible. This is because Parliament elects the president who in turn is required to be accountable to it. In practice, this means the party with majority seats in Parliament decides who becomes the president. And such is given the authority to constitute the national executive to implement the governing party’s electoral mandate. It is, therefore, not possible for the SONA not to have a partisan slant. Likewise, the opposition parties’ reply to the address is bound to be partisan. Because of this, the address becomes the preserve for the contestation of political elites along ideological lines while those in whose name it is called are at a loss.

Transcend the parliamentary shadow

But, how can this be overcome? Perhaps the speech needs to appeal directly to the public. This is not only the function of its composition. When, where, and how the address is delivered matters. In the Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle’s words, the president “must not only try to make the argument of his speech worthy and demonstrative belief; but must also make his own character right and put his hearers, who are to decide, into the right frame of mind”.

Political scientist Samuel Kernell has a phrase for this: “going public” with the address. This means transcending parliamentary shadows for the public’s support of what the incumbent of the highest office in the land put forward as their vision and plans for the nation they lead.

But Parliament itself has become a distraction of the delivery of the address. Shouldn’t it, therefore, be discontinued as the platform for this?

The Constitution does not explicitly prescribe that the address should take place in Parliament. Its provision related to this only states that the president “is responsible for summoning Parliament to an extraordinary sitting to conduct special business”. But, the address has always been treated as that “special business”. The joint rules of Parliament prescribe the venue for this. It is the chamber of the National Assembly – meaning Parliament.

Optimising citizen’s engagement

Perhaps these rules should be reconsidered for the president to deliver the address from anywhere in the country. For what it is worth, this could be made and broadcast from Alexandra or Diepsloot in Gauteng, or from Alfred Nzo region in the Eastern Cape where the level of poverty is said to be at its highest – just anywhere to give the address a symbolism of identification with the nation. But the debate about the address should still take place in Parliament, although in a way that ensures active citizenry.

Technologies to make this possible exist but need to be fully explored. If strategically deployed, these could optimise citizens’ engagement with the state of the nation address. But digital inclusion needs to first be addressed lest technology exacerbates societal inequities.

That various media platforms broadcast the president’s SONA is something to leveraged on, including Government Communication and Information System’s efforts to make the address available in all eleven official languages. The use of community radio stations should be maximised as part of the broadcasting services for the address. They should be supported with the technology for realtime translation services for the address to be easily understood by different communities in the country.

Rethinking the way the State of the Nation address is staged is necessary to rekindle efforts to forge collective solidarity and national cohesion.

– Mashupye Maserumule is the professor of public affairs at the Tshwane University of Technology, and writes in his personal capacity.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press