Africa-Press – South-Africa. Snake experts are raising the alarm over a shortage of South African-produced polyvalent snake antivenom, as a production backlog is causing waiting times of at least six months for the delivery of the life-saving snakebite treatment.

The polyvalent antivenom is the gold standard for the treatment of venomous snake bites and is produced in Johannesburg by the South African Vaccine Producers (SAVP), a subsidiary of the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS).

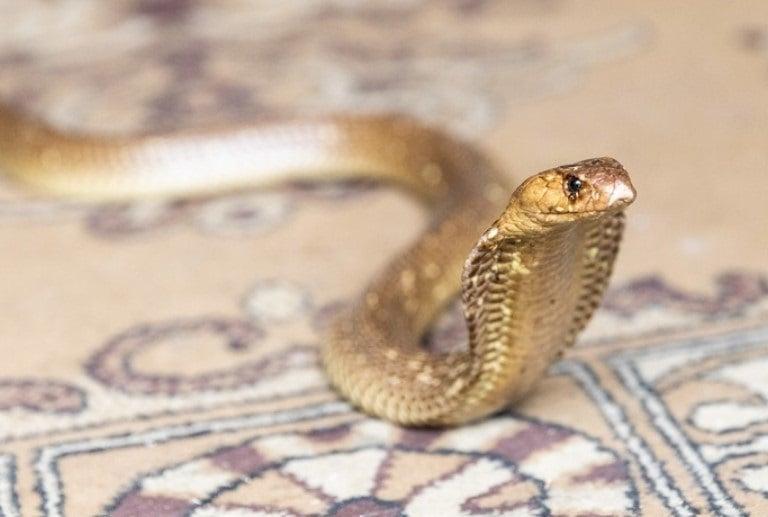

This antivenom (SAIMR Polyvalent Snakebite Antiserum SAVP) treats snakebites from the black mamba, green mamba, Jameson’s mamba, Cape cobra, forest cobra, snouted cobra, Mozambique spitting cobra, rinkhals, puff adder and Gaboon viper.

In the last few months, a massive production backlog at the SAVP has led to shortages at health facilities, especially among veterinarians, according to Johan Marais, herpetologist and CEO of the African Snakebite Institute.

“People’s dogs have died because, for the last eight months, veterinarians cannot buy antivenom. It really is a big problem,” said Marais.

He added that he had recently spoken to a medical doctor who couldn’t get his hands on antivenom.

Around 3 500 people are bitten by snakes in South Africa each year, with 800 hospitalisations, Marais estimated. Of these, only about 10% require antivenom treatment and, depending on the snakebite, treatments range from six to 20 vials per patient.

Marais estimates that there are 10 snakebite deaths per year in South Africa. The most recent cause of death data from Statistics South Africa found that there were 47 deaths from “contact with venomous animals and plants in 2018.

Marais said that bites from puff adders and Mozambique spitting cobras had to be treated quickly as they could cause severe tissue damage. If left untreated for too long, the patient may need multiple operations to repair the damage.

He added that the shortage had worsened in the last eight months. While it had previously been a problem, the current situation was worse.

Another challenge is that South Africa’s polyvalent antivenom is bought and used in other African countries, such as Kenya and Senegal. Kenya currently does not manufacture its own antivenom and experiences about 700 snakebite deaths per year, many more than South Africa.

Mike Perry, founder of African Reptiles and Venom, supplies the SAVP with the raw snake venom used to produce the polyvalent antivenom. He said it takes a few years to produce the antivenom.

Perry explained that the snake venom he supplied to the SAVP was injected into horses in low doses over long periods of time. When the horses become hyperimmune to the venom, blood is drawn from them and the antibodies against the venom are separated from the blood.

NHLS spokesperson Mzimasi Gcukumana told GroundUp that the SAVP was “working around the clock” to reduce and ultimately eradicate the backlog in antivenom production.

Gcukumana said load shedding had negatively affected antivenom production. He added that the laboratory had been able to supply “some provincial health departments and some private facilities, including 13 veterinary practices, during December to ensure there is adequate supply in the country”.

The laboratory said it planned to strategically place antivenom banks in high-risk areas across the country.

Department of Health spokesperson Foster Mohale said that it currently didn’t have a contract with the producer of antivenom, despite it being “an essential medicine”.

Mohale said the SAVP had informed officials that the “difficulty in sourcing the material” was the reason for the current low stock.

For More News And Analysis About South-Africa Follow Africa-Press