Africa-Press – Tanzania. THE Tanzania– Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA), widely known as the “Freedom Railway,” stands as one of the most remarkable infrastructure projects in modern African history. Constructed between 1970 and 1975 through a unique partnership between Tanzania, Zambia and the People’s Republic of China, the railway was conceived not merely as a transport corridor, but as a political, economic and diplomatic instrument. Its primary objective was to free landlocked Zambia from economic dependence on whiteminority-ruled regimes in Southern Africa by providing a secure alternative route for exporting copper and other goods to the Indian Ocean via the Port of Dar es Salaam.

At a time when Western nations had declined to support the project on the grounds that it was economically unjustifiable, China stepped forward with an interest-free loan and extensive technical assistance. In doing so, TAZARA became both a symbol of Pan-African solidarity and a defining example of China’s early engagement with Africa during the Cold War. Beyond its economic purpose, the railway embodied the ideals of self-reliance, South–South cooperation and political independence, even as it faced operational challenges that would require continued commitment and support to sustain its longterm viability.

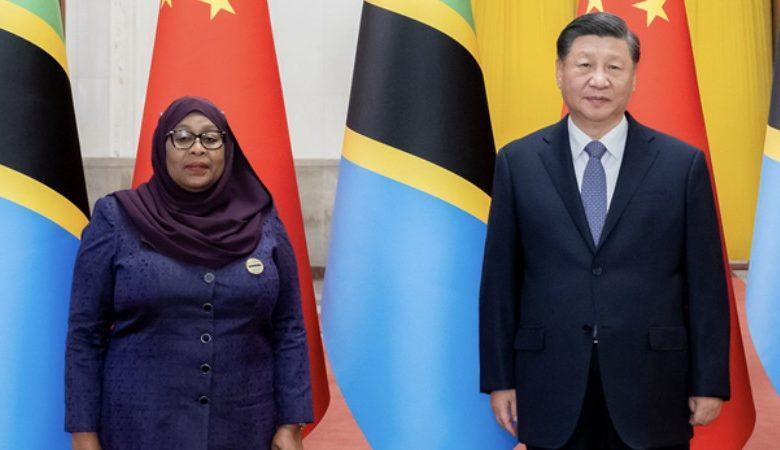

In my view, TAZARA represents one of the most ground-breaking examples of trilateral cooperation between African states and China. Its legacy continues to resonate today, particularly in the context of the strong and evolving Africa–China relationship, as demonstrated through platforms such as the Beijing Summit of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC).

Cold War origins and African self-determination

The history of TAZARA is inseparable from the broader global contest for influence during the Cold War. The railway was the vision of two towering African leaders: Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, the founding President of Tanzania, and Dr Kenneth Kaunda, who led Zambia— then Northern Rhodesia—to independence. Both leaders recognized that political sovereignty would remain fragile without economic independence. They envisioned a transport corridor linking the mineral-rich Copperbelt of Central Africa to the Indian Ocean, bypassing colonial and minority-ruled territories to the south.

The 1960s and early 1970s were years of intense liberation struggles across Africa. Newly independent states faced enormous pressure to assert control over their economies while navigating a world divided between East and West. For Tanzania and Zambia, self-reliance was not an abstract principle but a necessity. A reliable railway linking Zambia directly to the coast was central to that vision.

The two leaders approached international financial institutions and Western governments, including the World Bank and the United Nations, arguing that the railway would stimulate agricultural production, facilitate exports and enhance regional integration. These appeals were rejected. Western powers, notably the United States and the United Kingdom, declared the project economically unviable and declined to provide financing. Their assessments failed to account for the political and strategic realities facing the two African states.

China’s decisive intervention

It was in this context that Chairman Mao Zedong and the leadership of the People’s Republic of China accepted the challenge. In 1967, the governments of China, Tanzania and Zambia signed a landmark agreement in Beijing to construct the railway. China committed an interest-free loan of 988 million yuan—its largest foreign aid project at the time—along with technical expertise, equipment and manpower.

This commitment was made despite China’s own domestic challenges, including widespread poverty and food insecurity. Yet Chairman Mao recognized the strategic and symbolic importance of the project. Supporting TAZARA aligned with China’s broader vision of solidarity among developing nations and resistance to imperial domination. It also laid the groundwork for expanding China’s engagement with Africa, long before Sino–African relations became a central feature of global geopolitics.

The phrase “Tanzania and China are old friends” is one I have heard repeatedly from both Tanzanian and Chinese interlocutors. TAZARA is a powerful expression of that friendship.

Beyond financing, China provided engineers, surveyors, equipment, factories, workshops and training institutions. The goal was not only to build a railway, but also to transfer skills and foster self-reliance among African workers. In preparing to understand this history more deeply, I revisited Jamie Monson’s Africa’s Freedom Railway, which meticulously documents the geopolitical, social and cultural dimensions of the project.

Archival photographs from the period capture moments of genuine human connection: Chinese supervisors teaching young Tanzanians how to weld, or Chinese workers watching local football and basketball matches after long days of labor. These images reflect a period when Sino–African engagement was rooted in shared struggle rather than competition.

Nyerere’s reflections on gratitude and solidarity

During the construction of TAZARA, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere delivered one of his most memorable speeches reflecting on the nature of solidarity. He recounted visiting a construction site in Morogoro, where he spoke with Chinese technicians. The head of the team told him that they were grateful to Tanzanians for helping them build the railway.

Nyerere was initially taken aback—not out of offense, but out of reflection. The project, after all, was intended to benefit Africa. He later explained that young Tanzanians had joined Chinese workers to help carry construction materials. Yet the experience led him to ask a deeper question: who should truly be thanking whom?

In his view, it was Tanzania’s obligation to thank China for its assistance in building a railway that would serve Tanzanians and Zambians alike. This episode illustrates the humility and mutual respect that characterized the partnership.

Working relationships and cultural exchange

While no international relationship is without imperfections, many Tanzanians recall the Chinese presence during TAZARA’s construction as distinct from earlier colonial encounters. Chinese workers were widely regarded as disciplined and respectful. They adhered to strict codes of conduct, including prohibitions on alcohol and inappropriate relations with local communities. Many learned Kiswahili, and working on TAZARA became a rite of passage for young Tanzanian men.

These interactions fostered a sense of shared purpose that transcended cultural differences and reinforced the idea of collective achievement