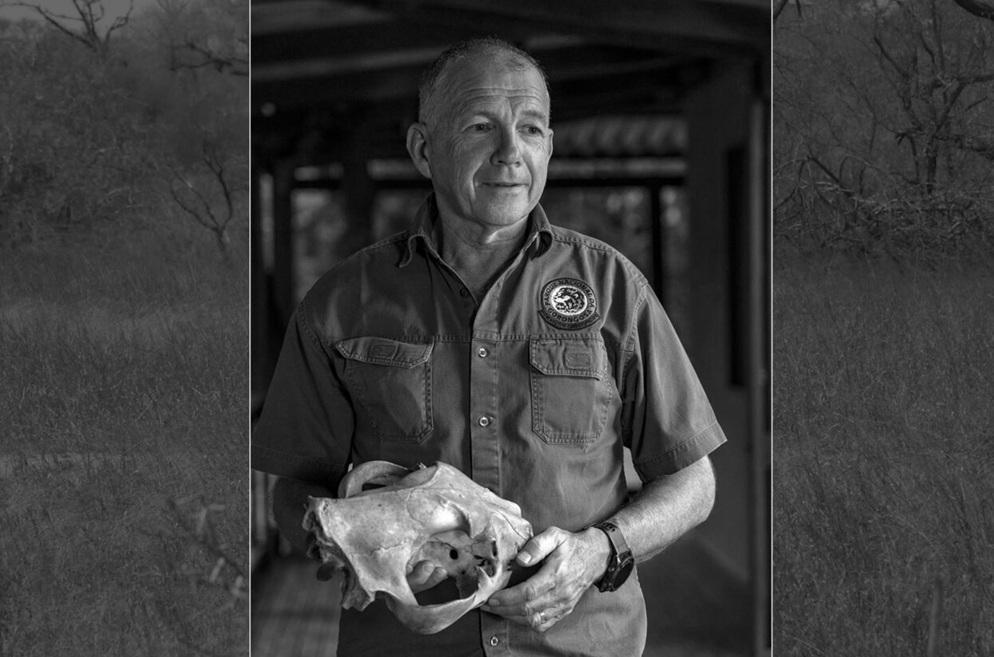

Africa-Press – Mozambique. Marc Stalmans, who died of natural causes on August 30th at 66, spent much of his life restoring life to a landscape once stripped of it. As the science director at Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park, he was central to one of Africa’s most ambitious ecological experiments: the attempt to bring back an ecosystem gutted by war. Gorongosa had been a battlefield during Mozambique’s civil conflict from 1977 to 1992. By the time peace came, its buffalo had fallen from 14,000 to fewer than 100, wildebeest from 6,000 to 15, elephants from 2,500 to under 200. Lions and wild dogs had almost vanished. The park, once a stronghold of African wildlife, was close to ecological collapse.

A post shared by Gorongosa National Park (@gorongosapark)

When Stalmans began working with the Gorongosa Restoration Project in 2006, he saw not just absence but possibility. “On the plant side, it was obvious when we first started that the general habitat was in very good shape. It was just the animals that were missing,” he recalled. With its rich soils, seasonal floods, and high productivity, Gorongosa had the conditions to rebound. What it lacked was the scientific guidance to ensure recovery took hold. In 2012, he joined full-time as science director, providing the data and ecological grounding for decisions about reintroductions, species balance, and land management.

Born in Kinshasa to Belgian parents, Stalmans moved to Belgium as a teenager and trained as a forestry engineer before emigrating to South Africa in 1984. He earned a master’s in botany and later a PhD in landscape ecology at the University of the Witwatersrand, combining research with decades of work in protected areas. His career was practical as much as academic: whether advising on fire regimes, measuring vegetation change, or calculating growth rates of buffalo and waterbuck, he used science to answer the pressing question of how an ecosystem stitched together by evolution might be stitched back together by people.

He saw science not as detached measurement but as a tool to guide action. When floods submerged large portions of the park in 2019, he studied dung samples and satellite images to understand how herbivores adapted to changed diets. The findings, he noted, could inform “the formulation of rewilding strategies in terms of the numerical balance between species.” He insisted that research mattered only if it helped managers make better choices.

Under his watch, Gorongosa became one of the best documented parks in Africa. The E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Laboratory, opened in 2014, has catalogued nearly 8,000 species, about 200 new to science. He championed training Mozambican students in ecology, believing the future of the park depended on local expertise as much as foreign philanthropy. Today more than 100,000 large animals roam there, ten times the number two decades ago.

He admired Sterculia appendiculata, a tall, pale-barked tree that grew on termite mounds, where plants and animals found nutrients against the odds. It was a fitting favourite. In a country scarred by conflict, he devoted himself to helping life rise again where it once seemed lost.

For More News And Analysis About Mozambique Follow Africa-Press