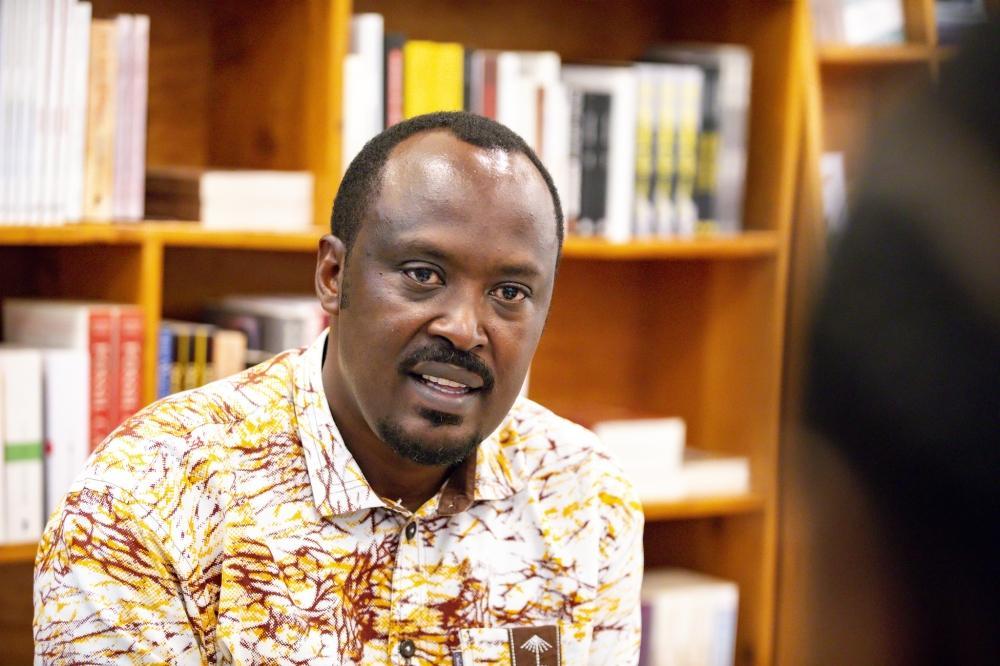

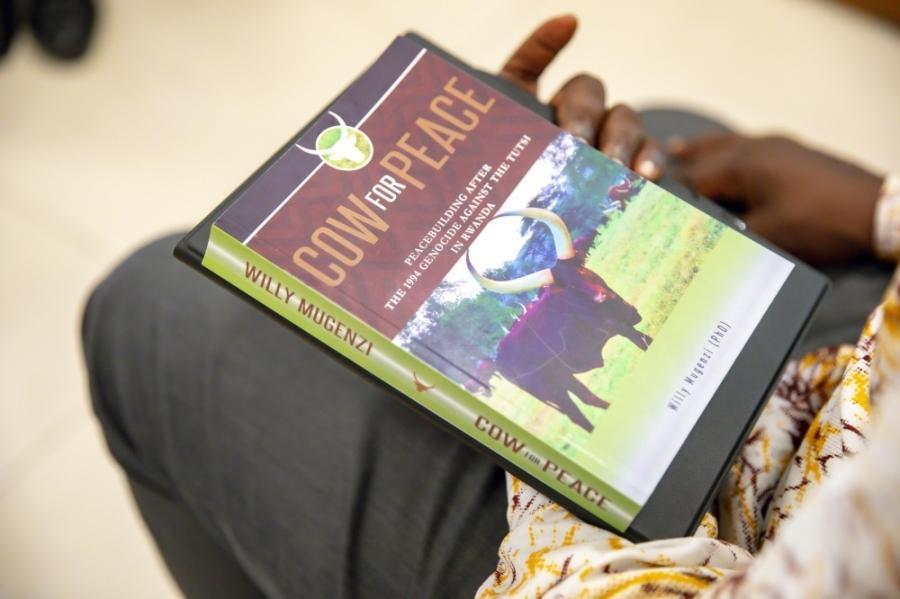

Africa-Press – Rwanda. In his book “Cow for Peace”, Willy Mugenzi does not present reconciliation as a slogan or a policy memo. He treats it as a social and existential necessity, something that belongs to today, tomorrow, and especially to young people who will carry it forward.

The book is grounded in doctoral research, shaped by lived experience, and animated by a central conviction: nations broken by mass violence do not heal by importing templates alone. They heal when they look inward, recognize their own cultural resources, and build institutions that speak to their history, texture, and needs.

This conviction runs through Mugenzi’s reflections on Rwanda’s post-1994 Genocide against the Tutsi journey—its hard choices, unfinished work, and the audacity of believing that culture itself could be mobilized as a national resource.

In conversation with The New Times, he returns again and again to a simple but demanding idea: peacebuilding is not charity, and it is not punishment for its own sake. It is the painstaking work of truth, accountability, memory, and social repair, done in public, owned by communities, and sustained across generations.

Childhood, curiosity, and the beginning of questions

Mugenzi traces his intellectual curiosity to an early love of reading and observation. As a young boy, he recalls being sent to the market with exercise books and newspapers, encouraged to read widely and early. Those habits, reading, questioning, and listening, became foundational.

Long before formal study, he was observing how societies organize themselves, how power speaks, and how ordinary people make meaning in the midst of hardship.

That early exposure to texts and ideas mattered later, when Rwanda’s history demanded more than silence or simplification. For Mugenzi, writing did not emerge as a hobby but as a response to questions that refused to go away.

Cow for Peace is both a backward and forward-looking work — rooted in memory, but oriented toward possibility.

What does it mean to rebuild trust after a genocide? How do you pursue justice without freezing a society in cycles of retribution? And how do you prevent denial, not only locally, but globally, when lies travel faster than truth?

From communication studies to peace scholarship

His academic path, from communication studies into peace and conflict scholarship, sharpened those questions. Communication, he argues, is never neutral. It shapes narratives, legitimizes power, and can either dignify or erase victims. Peace and conflict studies, meanwhile, offered frameworks to interrogate justice, reconciliation, and the long aftermath of violence.

Yet Mugenzi was never satisfied with theory divorced from context. He saw too many post-conflict societies struggle under the weight of imported models—well-intentioned, expensive, and often ill-fitting.

In conferences abroad, he was repeatedly asked how long it had taken Rwanda to rebuild. When he answered that culture had been central to the process, some listeners found it difficult to accept. The assumption, he noticed, was that solutions must come from the West, delivered through international expertise and funding.

Cow for Peace is, in part, a rebuttal to that assumption.

Why Cow for Peace had to be written

The book revolves around a question Mugenzi felt compelled to explore personally: what does it actually take to heal a nation after the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi? Not in abstract terms, but in daily life—how neighbours live again as neighbours, how perpetrators and survivors confront the truth, and how a society moves forward without erasing the past.

For him, the answer could not be reduced to punishment alone. Classical international justice models, he notes, would have taken more than a century to process the scale of crimes committed in Rwanda. Justice delayed at that scale would have been justice denied, leaving wounds open, truths buried, and denial fertile.

Instead, Rwanda turned to homegrown mechanisms that prioritized truth-telling, accountability, and social repair. These mechanisms were imperfect and painful, but they were rooted in Rwandan realities.

Situating Rwanda in global Genocide history

Mugenzi deliberately places the Genocide against the Tutsi alongside other genocides, from the Armenians and the Holocaust to Cambodia and Bosnia. This is not an exercise in comparison for its own sake. It is an insistence that Rwanda’s experience belongs within a global history of mass violence, denial, and the struggle for memory.

By situating Rwanda globally, he challenges exceptionalism and invisibility at once. The promise of “Never Again,” he argues, has been repeatedly broken. What remains realistic, and urgently necessary, is “Never Forget.” Memory—documented, taught, debated, and defended—is a safeguard against recurrence. Without it, denial fills the vacuum.

Memory over slogans: Why “never forget” matters

Mugenzi is blunt about the limits of slogans. “Never Again,” he suggests, has become aspirational rhetoric untethered from political will. Memory, by contrast, demands work. It requires societies to record who did what, where, how, when, and why. It requires education systems that confront history honestly, and scholarship that refuses to sanitize violence.

The book revolves around a question Mugenzi felt compelled to explore personally what does it actually take to heal a nation after the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi

In Cow for Peace, memory is not passive remembrance. It is active resistance to falsehood. In an age where misinformation spreads instantly, Mugenzi insists that scholars, writers, and citizens must occupy the narrative space—or cede it to denial.

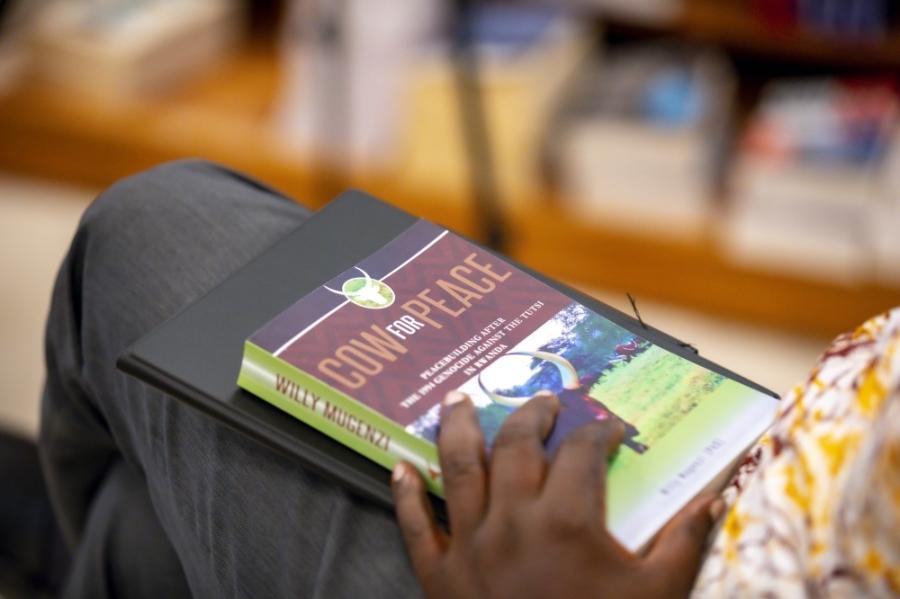

Girinka: When a cow became a bridge

At the heart of the book is the Girinka programme—One Cow per Family—which Mugenzi treats not as a welfare scheme, but as a culturally rooted practice of reconciliation. In Rwandan society, the cow carries deep symbolic meaning: life, dignity, continuity, and social bonds.

Through Girinka, survivors and perpetrators were linked in relationships that demanded responsibility. The programme was not about charity. It was about restoring livelihoods, rebuilding trust, and embedding reconciliation in daily economic life. A cow given was a commitment—to care, to share, and to belong again to a community.

Mugenzi describes other cultural practices around cows—such as inka y’ubuzima (the cow for life, given to a woman after childbirth)—to show how deeply social repair is woven into cultural norms. These practices resonated because they were familiar, meaningful, and owned by the people themselves.

Justice reimagined: From punishment to accountability

A central argument in Cow for Peace is the distinction between punitive justice and restorative justice. Mugenzi is clear: the goal was not to avoid accountability. It was to redefine it.

“I am not aiming at punishing you for the sake of punishment,” he explains. “I am aiming at showing you what you did, having you express remorse, and allowing society to move forward.” In this vision, imprisonment alone is insufficient. A society must know the truth. Victims must be heard. Perpetrators must confront their actions publicly.

Gacaca and truth for peace

This philosophy found expression in Gacaca—often misheard or mistranscribed, but correctly understood as Rwanda’s community-based justice mechanism. Gacaca brought truth-telling into the open, in villages and communities, where crimes had occurred.

Mugenzi acknowledges the trauma involved. Some testimonies—especially around sexual violence—were devastating. Not all truths were told equally. Not all wounds were healed. Yet without Gacaca, he argues, Rwanda would still be buried under unanswered questions and unresolved grievances.

Truth for Peace, as he frames it, was about more than verdicts. It was about restoring social knowledge—correcting false accusations, identifying real perpetrators, and establishing a shared record of what happened.

Rwandanness as a Unifying Identity

Another pillar of Rwanda’s recovery, in Mugenzi’s analysis, is the deliberate cultivation of Rwandanness—a national identity that transcends ethnic divisions. This was not accidental. It was nurtured through policy, education, and public discourse.

In a society shattered by ideology, identity itself had to be reimagined. Rwandanness became a framework for belonging that rejected the binaries that had fuelled violence. For Mugenzi, this identity work was as critical as economic reconstruction.

Lessons for other post-conflict societies

Mugenzi is careful not to present Rwanda as a blueprint to be copied wholesale. His message to other societies emerging from conflict is simpler and more demanding: look inward. Identify your own mechanisms of justice and reconciliation. Give them space to operate.

Too often, he observes, societies abandon their cultural resources in favour of external solutions that are expensive, slow, and poorly adapted. Homegrown mechanisms exist everywhere, but they are rarely trusted—or funded.

Scholarship as responsibility

As a scholar, Mugenzi insists that research must do more than accumulate citations. Scholars, he argues, are expected to contribute to the generation of knowledge that informs policy and improves lives. Publishing is not vanity; it is responsibility.

In his own case, Cow for Peace includes recommendations—some of which later materialized, such as the institutionalization of peacebuilding frameworks. These developments did not trigger personal pride, he says, but affirmed the value of engaged scholarship.

Writing against denial

Genocide denial, Mugenzi warns, will persist for decades. The fight against it cannot be left to institutions alone. It requires writers, researchers, and citizens to document, digitize, and disseminate homegrown solutions and historical truths.

He draws a parallel with military strategy: winning battles is not enough; narratives must also be told. If those who lived the truth do not tell it, falsehood will.

Making time to write

Balancing public service, leadership roles, and writing is not easy. Mugenzi describes long nights, sacrificed social events, and significant personal investment in books and research materials. Writing, for him, is a choice rooted in interest and urgency. If a question burns strongly enough, time is made.

Reading, youth, and the future

At a moment when reading culture is shrinking among young people, Mugenzi’s message is direct and unapologetic: there is no shortcut to building critical consciousness, national resilience, or intellectual independence without reading. For him, the decline of reading is not merely a cultural concern; it is a strategic vulnerability.

He situates this worry within a broader global context where noise, speed, and distraction increasingly replace reflection and depth. Social media, he argues, has amplified opinion without accountability, visibility without substance, and influence without evidence. In such an environment, societies that stop reading risk outsourcing their thinking to louder voices elsewhere.

“Almost 90 per cent of African countries say they want to become knowledge-based economies,” he notes. “But there is no way you become a knowledge-based economy if people are not reading. It is impossible.”

Mugenzi traces his own relationship with reading back to childhood. Growing up, he would carry exercise books to the market, where vendors exchanged newspapers for empty notebooks.

Those early encounters with print — long before academic ambition or professional titles — shaped his intellectual discipline. Reading was not an elite activity; it was a habit, a way of understanding the world.

That habit, he believes, must be intentionally rebuilt among young people today. Not through slogans or moralising lectures, but by demonstrating that reading sharpens agency. In a global labour market, he argues, youth do not sell nationality or sentiment — they sell ideas, skills, and the ability to persuade.

“What you take to the global market is your brain,” he says. “Your capacity to think, to convince, to analyse — these are the real commodities. They are not inherited. They are built.”

For Mugenzi, writing Cow for Peace was therefore not only an act of scholarship or memory, but an intervention into this crisis of attention. He worries that when scholars fail to publish, when thinkers retreat from public discourse, a vacuum emerges — one quickly filled by denialism, distortion, and simplistic narratives.

“Today, anyone can sound like an expert,” he reflects. “And because those who have done the work are silent, people who have not read, not researched, not reflected, dominate the conversation.”

The role of scholars in changing narratives

This is why he insists that African scholars, writers, and thinkers must occupy both academic and public spaces. Knowledge, he argues, has no value if it remains locked in classrooms, conferences, or unpublished dissertations. It must circulate, provoke questions, and invite contestation.

“You are expected, as a scholar, to contribute to the generation of knowledge,” he explains. “But also, to policy improvement, to social understanding, to peacebuilding. Scholarship is not decoration. It is responsibility.”

That responsibility, in his view, is especially urgent in the ongoing battle over genocide narratives. Denial, he reminds us, is not a closed chapter but a recurring stage. It mutates, travels, and adapts — particularly in digital spaces where historical distance weakens emotional connection.

“If lies spread faster than truth,” he says, “it is because truth is not being told enough.”

Books, then, become more than repositories of memory; they are defensive structures. They slow down falsehood, anchor evidence, and preserve nuance in a world increasingly allergic to complexity. Writing is not a luxury — it is a form of resistance.

Mugenzi extends this argument to parenting and intergenerational responsibility. If there is one inheritance he values above all others, it is not property or status, but books. Reading, he believes, forms character before it forms careers. It disciplines patience, cultivates empathy, and trains the mind to connect cause and consequence.

“When you read,” he says, “you learn that things do not happen randomly. You learn how societies rise, how they fall, and how they can repair themselves.”

This belief shapes his appeal to Rwanda’s youth: do not imitate blindly, and do not outsource imagination. Rwanda’s culture, history, and homegrown solutions, he insists, are not relics of the past but renewable resources for future greatness.

“Imitation has limits,” he says. “Why not build your own? Why not use your culture as a resource for innovation?”

In this sense, Cow for Peace is both a backward and forward-looking work — rooted in memory, but oriented toward possibility. It is a call to read deeply, think independently, and write courageously. Because, as Mugenzi reminds us, nations that stop telling their own stories eventually live inside other people’s versions of them.

And for a country that has already paid the price of imposed identities and external narratives, that is a risk Rwanda cannot afford.

For More News And Analysis About Rwanda Follow Africa-Press