Africa-Press – Angola. President Joe Biden came into office eager to turn the page on his predecessor’s disdain and disinterest in the African continent.

Instead of hurtful digs about “shithole” countries, the new administration promised a new era of relations based on common interests and mutual respect. The US, Biden’s White House asserted, should be Africa’s ideal partner on everything from nation-building, to trade, to security.

Almost two years into his first term, the president’s record on Africa is about to come under the spotlight like never before.

After months of back-and-forth between federal agencies, Secretary of State Antony Blinken in August finally released the administration’s new US strategy for sub-Saharan Africa. This December, Washington will host a US-Africa Leaders Summit for the first time since President Barack Obama launched the idea in 2014.

Together, the strategy and the summit encapsulate Biden’s vision for developing business ties with a youthful continent seen as a future economic powerhouse while staving off inroads by China and Russia. At the same time the administration has recommitted to the longtime US policy of supporting democracy in Africa and around the world after four years of “America First” priorities under President Donald Trump.

“There was definitely a deliberate departure from the way that the Trump administration talked about and engaged with Africa,” says Akunna Cook, a Nigerian-American former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs who left the government in September to launch a media production company focused on Africa. “The bar was at the floor of how you could elevate the discourse on engagement with Africa and base it on mutual respect.”

Now comes the real test of whether US-Africa ties will finally take off or continue to fall far short of their full potential.

US appeal

On paper at least, the US has a lot going for it.

African governments and their citizens may resent western lectures about the risks of dealing with China – the continent’s biggest trading partner for the past 13 years – and admonishments to denounce Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But many still look to the United States as a force for good.

Polling by Afrobarometer indicates that 60% of Africans believe the United States has had a positive economic and political influence on their country, just below China (63%) but far ahead of Russia (35%) and former colonial powers (46%). At the same time, 70% of Africans agree with the statement that “democracy is preferable to any other kind of government.”

The new US strategy takes such findings into account to make the case that democratic African nations are more likely to choose the US as their preferred partner. As such, the document urges intensified US support for a free press, rule of law and transparency across the continent.

“Open societies,” the strategy states, “are generally more inclined to work in common cause with the United States, attract greater US trade and investment, and pursue policies to improve conditions for their citizens, and counter harmful activities by the People’s Republic of China, Russia, and other actors.”

In order to engage with Africans on their own terms, the Biden administration is also looking to leverage America’s 2 million-strong Africa-born diaspora like never before.

“That competitive advantage right now is latent,” says Zainab Usman, the head of the Africa programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. “It hasn’t yet been realised, but it’s there to be tapped.”

Falling short

Even as the Biden administration is saying a lot of the right things, critics argue that more can and should be done to really prioritize Africa.

As of mid-September, neither President Biden nor Vice President Kamala Harris had yet to conduct – or even announce – a visit to the continent. The last US president to travel to Africa was Obama in July 2015, when he stopped by Kenya and Ethiopia.

By contrast, Biden so far has conducted eight international trips to 13 countries in Europe, Asia and the Middle East (plus the West Bank), including his 19 September visit to London for the state funeral of Queen Elizabeth II. Meanwhile Chinese President Xi Jinping last visited Africa in 2018 shortly before the Covid epidemic while Russian President Vladimir Putin stopped by South Africa for the BRICS summit that same year.

“I think there’s just a mismatch between the level of engagement (and the rhetoric) that comes out of partly the United States having so many interests around the world, and many demands on its time,” says Cook. “But also just, frankly, a (lesser) priority placed on Africa.”

Pro-democracy activists also worry about America’s continued support for the region’s autocrats despite its pro-democracy rhetoric.

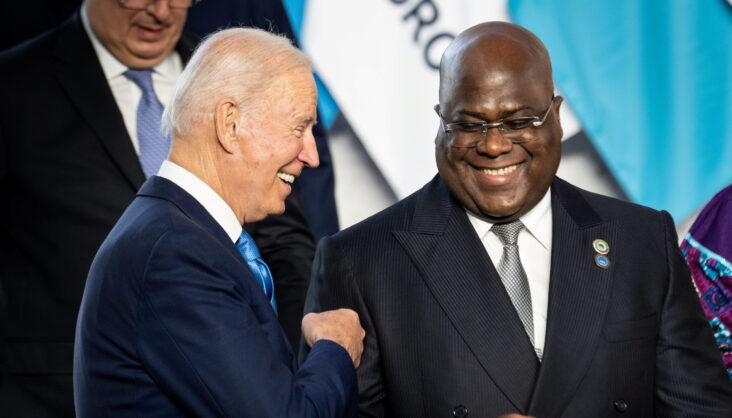

This year the Washington think tank Freedom House scored only eight African countries as fully free (Botswana, Cabo Verde, Ghana, Mauritius, Namibia, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles and South Africa) – the worst showing since 1991. By inviting a host of leaders of authoritarian countries to its Leaders Summit, from Cameroon to Uganda, President Biden is giving them all a golden chance to pose with the leader of the free world without having to make any changes to earn it.

“There’s a significant – and some could argue growing – chasm between rhetoric and reality,” says Jeffrey Smith, the founder of Vanguard Africa, a US consultancy that represents African opposition figures such as Uganda’s Bobi Wine and Martin Fayulu of the Democratic Republic of Congo. “I think that’s always a problem, because then America’s detractors can point to that very void, and they’re not wrong about that.”

Key to the summit’s success, Cook says, will be how well the US can engage Africa on a host of issues from increasing private sector investment, to boosting Africa’s voice in international organizations, to helping the continent meet its huge energy needs in a sustainable way.

“I think the fear is that it’s a check-the-box exercise. Like, okay, there’s so many African countries, and if we just bring them all here … that’s it,” Cook says. “But that’s not really what you want out of a summit. What you need out of a summit is something that meaningfully sets an agenda that you can work on for the next year or two years.”

For More News And Analysis About Angola Follow Africa-Press