Africa-Press – Cape verde. The history of pottery in Boa Vista is made of sand and memory. Once a pillar of the country’s economy, it is now undergoing a period of recovery and adaptation to tourism, under threat of a fragile future.

The testimony of three generations of potters, from the colonial period to the present, traces the trajectory of an art that has refused to die, but fears the fragility of its succession due to a lack of youth support.

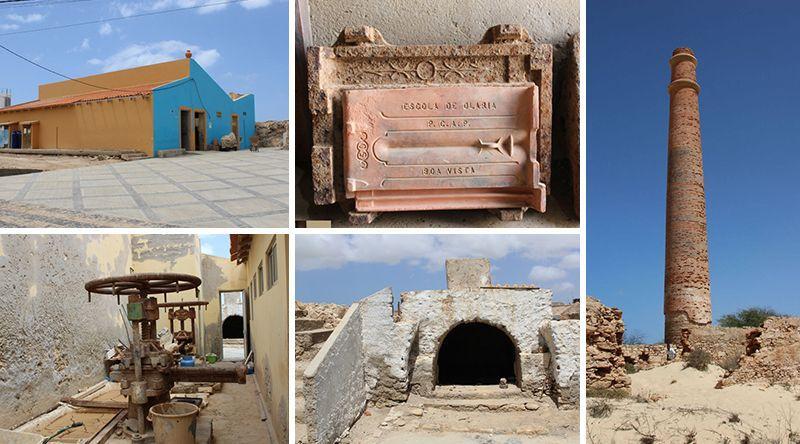

At Chaminé de Chave, one of the island’s tourist attractions, its ruins are a testament to an old brick and tile factory. A thriving industry that once existed on the island, exporting primarily to West African countries, closed in 1928 for unknown reasons.

According to data from the Boa Vista (Official) Cabo Verde tourism website, another project operated on the same beach, the Chaves Pottery School, also a weaving factory, started in the late 1950s, but also closed due to the independence movement.

The writer Germano Almeida himself described Boa Vista as the “island whose name was invoked daily on the other islands,” as it provided tiles that covered many houses in the archipelago, and clay containers and pots that kept water fresh.

The Boa Vista Pottery School, as former potter Afonso Fernandes, 73, recounts, was founded around the 1960s by a Portuguese man, initially in a house in Riba Rotcha, in Rabil, and later moved to the current Rabil Pottery School.

He states that he worked at the Pottery School in 1971 and recalls that the work of making tiles “was rough.” Men and women removed the clay from the wall, which they carried, and dumped it into a tank, letting it soak and be kilned.

It was then used in molds for tile-making machines, which, although rusty, still exist at the school, as does the kiln.

With the arrival of Independence in 1975 and the closure of the colonial structures, the Pottery stopped. According to Afonso Fernandes, it was apparently no longer profitable, especially with the arrival of cement and plastic, which “regrettably replaced clay.”

After the closure and abandonment of the space, potter Antônio Monteiro, also known as Toni d’Jovina, 64, and the Pottery’s reactivator, described how in 1982 “they made charcoal inside; it was a garbage dump.”

Motivated by the tradition inherited from his mother, Tóni d’Jovina took on the task of reviving the site, cleaning and building walls to protect the clay from the island’s wind.

With the support of city hall initiatives, the school opened in 2008.

From producing roof tiles, they moved on to artistic crafts, such as vases and the famous turtles, which are geared towards tourism.

Despite the cultural importance of pottery, the future of the tradition is the main concern, as explained by potter João Morais, also known as Luta, 48. He highlights the problem of generational succession, where economic fragility threatens the legacy, as artisanal work, while beautiful, offers neither security nor remuneration that attracts young people.

To ensure the future of this art, potters are asking for institutional support focused on modernization.

Tóni d’Jovina dreams of an industrial kiln to produce tiles and bricks for local construction, and Luta emphasizes that an industrial kiln would allow for increased production, secure orders, and consequently offer better wages to attract young apprentices.

The Rabil Pottery is seen as one of the great symbols of Boa Vista and a “source of income” that needs to be developed.

Its survival depends on the Government and the City Council ensuring that the economic structure supports the transmission of the tradition, forged through the efforts of several generations, and that it continues to shape the island’s cultural and economic future.

For More News And Analysis About Cape verde Follow Africa-Press