Africa-Press – Lesotho. At the dawn of the Third Millenium, I initiated a graduate study programme: Master of Education — African Studies in Science Education. The programme sought to spark institutions to rethink their higher education curricula.

The dream was to share this programme with African universities across the continent. Sadly, like Dr Nkrumah’s United States of Africa and Dr Martin Luther King’s speech, “I have a dream.

.

.

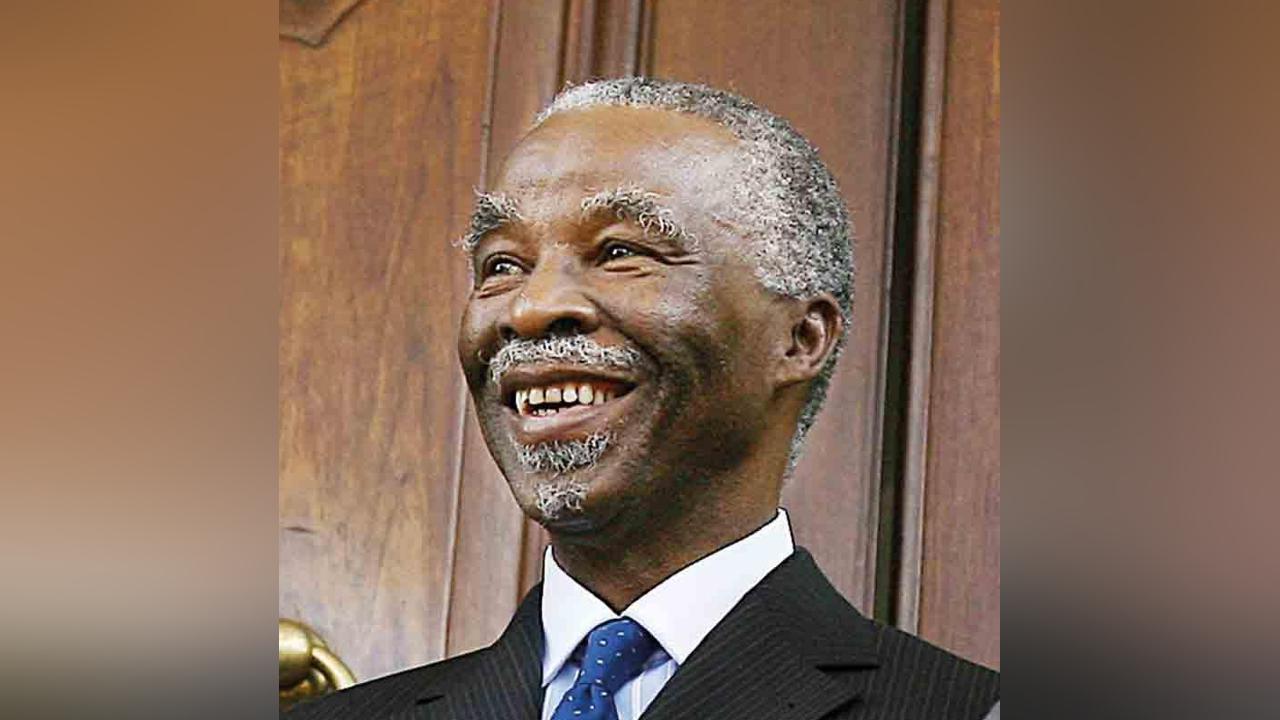

” these remained a “dream”! The programme idea came against the backdrop of several African developments. For example, the apartheid regime collapsed in South Africa. Thabo Mbeki made the: “I am an African” speech when he launched the African Renaissance.

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) became the African Union (AU) after the 1999 declaration by the Heads of States. Then there was the University of Timbuktu recovery and restoration debates and many others.

In the meantime, Lesotho promulgated several education acts. These include the Higher Education Act of 2004 and the Lesotho Qualification Framework Act of 2005.

The Higher Education Act of 2004 established the Council on Higher Education (CHE), which regulates the higher education system. The CHE is the custodian of higher education quality assurance and facilitates social transformation and development.

Lesotho’s higher education system desperately needs to meet these imperatives. I wish to share my experiences with something closest to my heart, namely, Basotho students’ access to and success in the science field, particularly their success in this at the higher education level.

I am a science teacher by training. My interests include science and higher education research and making school science, mathematics, and higher education accessible to the underprivileged.

This article grapples with the implications of the envisaged Master’s programme for African higher education in the 4th industrial revolution and the post-Covid-19 global pandemic era.

I recently discussed the unemployment of teacher graduates with a colleague in the pre-service teacher education space. He explained that they are exploring intensifying their teaching majors to empower graduates to become entrepreneurs.

So I wondered, is teacher education looking to empower students to become entrepreneurs in areas other than teacher education? The revelation acknowledges that there are challenges in Lesotho’s higher education system if the supply-demand chain is disturbed.

It became clear that teacher education curricula or the entire formal education curricula needs reviewing. Napoleon Hill warns that educational institutions do not teach students how to organise and use their acquired knowledge.

He points out that knowledge has no value unless people can apply it to something worthy. If graduates cannot use their ‘teacher-training’ knowledge, it represents miscellaneous knowledge.

Teacher education curricula could include entrepreneurship skills in personal development and facilitation because teachers already have presentation skills.

They need to explore a different audience rather than a school education. Perhaps an adult audience. So they could repackage their curricula for this new endeavour.

The endeavour to intensify teaching subjects content may not necessarily be the solution. Professions and occupations demand specialised knowledge. But, institutions should be cautious about how they approach this endeavour.

Curriculum design is an ongoing process. So the colleague makes a profound acknowledgement. The curriculum must respond to society’s needs and endeavours to address them.

An academic department must seek to make its curriculum relevant at all times to respond to the surrounding developments. Curriculum design is a process with which institutions of higher learning must continually engage.

The curriculum process involves the re-contextualisation of knowledge by selecting and ordering it. Broadly, the curriculum process works with the packaging knowledge to serve social needs. In short, this is the interaction of knowledge with society.

In the context of my interest and pursuit of increased access to science and science at the higher education level, we must first conceptualise science education and place it in the context of our programme.

Then, this understood meaning would inform the nature of the ensuing curriculum. Let me begin by presenting some views of science education. One meaning of science education focuses on the didactics of science.

In this way, science education facilitates the learning of science in schools. Also, commonly, science education relates to science teacher education.

An African scholar, Uchenna, defines science education as the study of the inter-relationship between science as a discipline and the application of educational principles to its understanding, teaching and learning.

But this definition limits the discipline. There is a need for a more encompassing definition relating to a broader purpose of education. According to Osborne, the goal of any science education is to develop scientific literacy and explore what that might consist of and why such education is necessary for contemporary society.

Osborne’s definition is similar to that of Yager. Yager explains science education as the study of the impact of science on society and vice versa. So, science education is a discipline concerned with the interaction of science and society.

One may infer from the above definitions that science education seeks to explore the interphase of science and society. But, the inference applies to education in general.

Education is the interphase of knowledge and society. Accordingly, the Master of Education: African Science Education sought to grapple with science education in an African society.

Here I will use an argument I put elsewhere. I argued that for Lesotho to liberate itself, Basotho must disentangle themselves entirely from the bondage of colonialism.

The proposed Master’s programme sought to drive the research agenda to emancipate Africa fully. Science education for the betterment of African society.

This ambition applies to higher education, in general. The CHE reiterates this purpose for Lesotho in its report on the status of higher education in 2020.

Elsewhere, I explained that sociologist Basil Bernstein devised a framework for translating knowledge into pedagogy, which, in doing so, helps organise knowledge into teaching. He called this the “pedagogic device”.

Also, readers must remember that the core business of a university is knowledge production – research, knowledge re-contextualisation — teaching and learning, and community outreach.

Bernstein’s pedagogic device helps to understand the interaction between knowledge production and society. Regardless, focusing only on African Science Education is limiting. I broaden my concerns to African higher education studies. Here Mills’ view of transformation applies.

Mills says transformation entails dismantling a colonial system that keeps re-writing itself by conditioning what we can think, do and believe well after the demise of colonisation.

I will then look to understand the subject in the post-colonial African context. The reader must remember that while Africa is now independent, most countries are deep in debt.

Many are engulfed in civil wars and are on the brink of becoming “failed states”. Many depend solely on foreign donor agencies. Many believe that science and mathematics education will enable Lesotho to disentangle itself entirely from the bondage of colonialism.

Regardless, Africa requires education empowering countries to break the cycle of poverty, misery, and disease. Currently, African higher education curricula mirror western ones.

African curriculum must distinguish itself in its uniqueness. So, African scholars must drive all education processes. I have listed these in this article.

The word ‘university’ denotes universal knowledge. However, it is a fallacy that knowledge is universal. To whom is it universal? In our education system, where there is so much disparity, knowledge is ‘universal’ to the ‘haves’, the elites.

When government systems exclude the marginalised, these will not benefit from the ‘universal’ knowledge. The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the already desperate predicament.

There is a need, therefore, for research to explore ways of overcoming this awkward predicament. This Master’s programme could provide a platform for such research studies.

Placing the qualification at a Master’s postgraduate studies level was deliberate and strategic. Master’s is the entry point for research studies. But more importantly, Master’s prepares students for entry into doctoral research studies.

The research will be carried out in our context, driven by our scholars. Africans would own the knowledge they produce. The envisaged Master’s programme comprises two components, coursework and a research dissertation.

Consecutively, the coursework component consists of several modules or courses. The modules would help students to find their research topics. Thus, it would enable students to handle contextual issues relating to African science and higher education on the continent.

However, the programme’s intention was not to confine students’ research topic selections. The research component would develop students’ research skills.

This component would serve two more purposes, namely; developing professional researchers and preparing students for entry for their doctoral research studies.

Consequently, teaching these subjects at the Master’s level will help the institution realise their core functions. Professional research includes research in the areas of curriculum development.

For example, I referred to a colleague’s complaint about graduates’ unemployment. Some suggest that a solution is introducing entrepreneurial skills in qualification, but this may not necessarily be the solution.

Here I would refer the reader to what Hill said about specialised knowledge. If the inclusion of entrepreneurial skills is a solution, it may not be the only one.

Only research can help confirm the needs. Unemployment of graduates could be a research topic or area in the Master’s qualification. Therefore, institutions and academic departments must base their programmes on research studies, not on mere hunches or institutions.

There must be consultations with peers and fellow professionals. A couple of years back the Lesotho government shut down the Lesotho School of Medicine (LSoM), saying that those were the recommendations of the CHE.

The Government, then, was dishonest. The CHE highlighted the LSoM’s shortcomings and made recommendations. Nowhere in the report did the CHE say the LSoM must shut down.

The CHE’s evaluations are developmental to help institutions improve the quality of their offerings. Not punitive. Our African studies would support initiatives such as the defunct LSoM’s Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery programme.

The qualification was a Basotho initiative. Basotho professionals would teach it to Basotho students. In short, the degrees were an African initiative to improve Basotho’s quality of lives.

Lesotho’s Ministry of Economic Planning wrote several Five Year National Development Plans. Common to all these and reiterated by the new Prime Minister in his inauguration speech is the need to focus on developing human resources, the country’s most important resource.

The CHE report lamented the dismally low research output in Lesotho. After the break up of the University of Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland (UBLS) to give birth to the National University of Lesotho (NUL), people referred to the NUL as a “glorified high school”.

The reference sounds derogatory because universities generate knowledge. After all, high schools consume curricula from elsewhere. But, alas, according to the CHE, this may not be true for Lesotho.

Local higher education institutions (HEI) use foreign textbooks. If our HEIs conduct research, we will become fully liberated and independent to drive our development agenda.

The lack of research is a severe hindrance to developmental progress. It deprives Lesotho of the necessary knowledge enabling Lesotho to progress into the Fourth industrial revolution.

The higher education system needs drastic innovation to help shift from pure knowledge reproduction (teaching) to knowledge production (research). The Master’s programme had a module that would explore contemporary continental developments.

The developments could be continental, regional or national. The examples included SADC (Southern African Development Community) and its troikas, OAU (now AU) and the African

Development Bank, the African debt, the Beijing Women’s conference, gender and social justice issues, including local National Assemblies legislature processes — green and white papers, bills and acts.

The module assessed the implications of these developments to science education and education in general. African Studies in higher education would not be complete without an audit of the active contemporary actors in knowledge production.

These are the drivers of knowledge in our education systems. At a local level, the studies would seek to understand the demography of the active research scholars to understand what drives them and the nature of their research.

The studies would also suggest mechanisms for persuading non-active scholars to participate in scholarly research. One such initiative could include running staff mentorship programmes.

I have such a model in place. Often when one brings up discussions on higher education in post-colonial Africa and a Master’s programme such as this one, the issue of indigenous knowledge crops up.

Many argue that our study programmes sought to push back indigenous knowledge out of the mainstream education agenda. Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) is part of the Master of Education in African Studies in Science Education.

However, it includes other study areas. Removing IKS from this programme would be criminal. There is a rich science and mathematics that the ancient Africans, including Basotho, practised.

Much of that knowledge is still relevant today. Smelting of iron, pottery, brewing sorghum beer, San people hunting, the science in the Egyptian pyramids and early civilisation and many others are examples of African

indigenous knowledge. These studies should go beyond sociology and anthropology. I have written about some of these studies under this column in this publication.

There are lessons to be learned by our generation. These lessons would not serve as tourist learning. They provide a deeper understanding of the science and mathematics that informs them.

This area also makes a rich research area. But for students to proceed into a Master’s qualification, they must hold a relevant bachelor’s degree. Also, the CHE observed an oversubscription of diploma qualifications in Lesotho’s HEIs.

Many of these are not in strategic disciplines that enable Lesotho to develop in the desired direction. African Studies in Higher Education suggests an overhaul of the higher education system.

Institutions would re-look at their programme qualification mix and introduce relevant degree programmes. However, institutions must design new programmes based on situational (or needs) analysis.

For example, Lesotho colleges must add cognate bachelor degrees to their programme qualification mix. In summary, this article uses an earlier conceived Master of Education: African Studies in Science Education to give meaning to the African higher education system.

I have combined the definition of science education with Bernstein’s pedagogic device to extend this meaning to African higher education. I built an argument for knowledge production and research in our HEIs CHE has confirmed the low research production in Lesotho’s higher education system.

I have given examples of some modules that made the Master’s . These modules distinguish our African Studies Master’s from those studied elsewhere. For example, not only did the Master’s explore African IKS, it critiqued contemporary developments.

The article suggests that the masters degree would enable our HEIs to identify their research strengths. The strengths include identifying the active actors, the areas, and the dominant methodologies.

So, these analyses would not be mere journalist inquiries but are in-depth research to build on. These institutions would then seek ways that they could use this to empower their academics to become researchers and drive the knowledge production, re-contextualisation, and pedagogy agenda.

I use the experience of a higher education colleague to highlight the utility of acquired knowledge. Graduates must meaningfully apply their acquired knowledge.

Otherwise, the ‘learnt’ knowledge is valueless. The article highlights the need for incorporating indigenous knowledge systems by giving some examples of science education in this article.

But I have also made a case for going beyond science education to include other fields. For example, there is a need for in-depth research on using the IKS to improve the quality of life today.

Lastly, I used the CHE recommendations and the need for higher education to fulfil its mandate for research output to argue for an increase in the bachelor’s degree programmes.

According to the CHE, Lesotho has an oversupply of diploma qualifications. Institutions must review their programme qualification mix to align them with the country’s strategic aspiration.

In conclusion, it is time the African education system replaced the existing Eurocentric higher education systems with Afrocentric ones. For Africa to become free, indigenous Africans must drive our knowledge agenda.

As a result, such a higher education system must make Lesotho develop the human capital capable of helping the country solve its socioeconomic challenges leading to complete liberation. Nonetheless, African scholars should guard against being assimilated back to Eurocentric bourgeoisie tendencies.

For More News And Analysis About Lesotho Follow Africa-Press