What You Need to Know

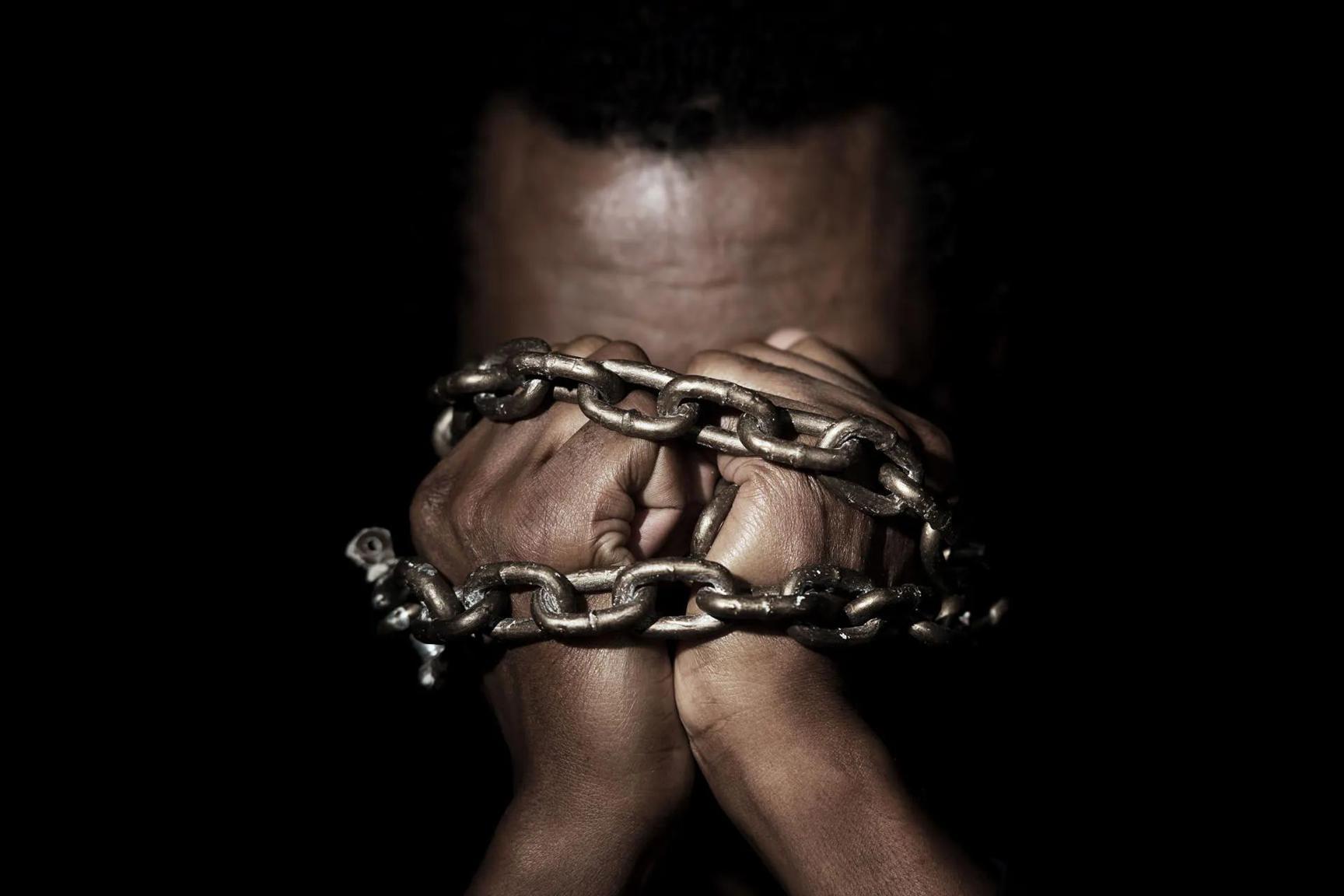

As the UN General Assembly approaches, Ghana seeks to revive the issue of the transatlantic slave trade. President John Mahama plans to submit a resolution to classify the slave trade as a crime against humanity, coinciding with the International Day of Remembrance for Victims of Slavery. This initiative has garnered broad support across Africa.

Africa-Press. As the meetings of the United Nations General Assembly approach, Ghana appears to be on the threshold of a historic opportunity to revive the issue of the transatlantic slave trade, drawing on its historical position as the main departure point for enslaved Africans toward the Americas and Europe, as well as on continental and international support. This comes amid a noticeable Western retreat from recognizing international principles related to the right to reparation, rehabilitation, and redress.

At the African summit held in Addis Ababa in mid-February, Ghanaian President John Mahama announced that his country would submit a draft resolution — which has received broad African support — to the United Nations General Assembly. The resolution aims to classify “the slave trade in Africa” as “the gravest crime against humanity” on March 25, coinciding with the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

In his closing remarks at the conference, Mahama stressed that the adoption of the UN resolution “will not erase the history of transatlantic slavery, but it will acknowledge it,” emphasizing that it is not directed against any particular state. He underscored that the issue will not be limited to demanding financial compensation, but primarily seeks to restore historical rights and to establish global recognition of what millions of Africans endured.

The African mobilization toward UN recognition of the victims of the transatlantic slave trade has, according to the Ghanaian president, “made significant progress,” noting that the initiative “is firmly grounded in international law” and that slavery is prohibited under international law.

Three main pillars underpin the project, according to the Ghanaian president: historical accuracy, legal strength, and African consensus both on the continent and within the diaspora. He noted that his country has conducted extensive consultations including the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the International Group of Experts on Reparations, the African Bar Association, academic institutions, as well as the Committee of Experts on Reparations and the African Union’s Legal Experts Reference Group.

The next step for the draft resolution, after receiving continental endorsement according to Mahama, will be during the fiftieth regular meeting of the Caribbean Group in New York. He affirmed that Africa and the Caribbean states “speak with one voice” on reparations, given their shared history, alongside intensive diplomatic consultations with the Non-Aligned Movement, the Group of 77 and China, the European Union, and other regional blocs, in preparation for building broader international consensus around the draft resolution.

Ghana is also scheduled to host a high-level event at the United Nations on March 24, followed by a wreath-laying ceremony at the African Burial Ground Memorial in New York. The resolution will be formally presented to the General Assembly the following day, coinciding with the International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade, while keeping all future options open, including legal avenues. However, the current focus remains on securing international recognition through the United Nations General Assembly, according to Mahama.

The colonial period in Africa extends from the mid-15th century to the mid-20th century. It began with the transatlantic slave trade, which reached its peak with the establishment of British colonies in the Americas during the 16th and 17th centuries.

In its early stages, the trade responded to external factors, including increased demand for labor in Portugal and Spain, as well as in African Atlantic islands such as São Tomé, Cape Verde, and the Canary Islands (west of the continent), as noted by the Guyanese historian of African descent Walter Rodney in his 1972 study Europe and the Underdevelopment of Africa, which traced the system of the transatlantic slave trade (the Middle Passage).

Subsequently came the phase during which Caribbean and American societies required African laborers to replace Native Americans who had been victims of genocide. A need emerged to meet the demands of these societies and to cultivate their lands. According to Rodney, the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), which Europeans referred to as the “Slave Coast,” was the departure point of this trade.

In later stages, with the onset of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe in the mid-18th century, European interests shifted from trading enslaved people to trading African commodities. Although the transatlantic trade was abolished on March 25, 1807, under a British law, slavery remained central to British interests in their colonies. The United Nations has designated this date as the “International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.”

Following the abolition decision, Britain launched a major campaign to suppress the trade. It dispatched its fleets to the African coasts and concluded a series of treaties with other states, allowing the inspection of ships suspected of carrying enslaved people. Africans freed from seized ships were transported to Freetown in the colony of Sierra Leone (West Africa). However, British efforts remained partial, as slave smuggling continued, and between two and three million additional Africans were transported to the Americas over the following half-century, particularly to Cuba and Brazil.

The 1880s witnessed the first multilateral treaties aimed at combating slavery. At the Berlin Conference (1884–1885) and the Brussels Conference of 1889, delegates of the European colonial powers, along with the United States, pledged to work toward ending the trade in enslaved Africans. Nevertheless, this pledge was used as a pretext to partition Africa into formal European colonies.

While Britain and France acquired the largest number of colonies, King Leopold II of Belgium was granted control over the largest territory in Africa (the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo), covering an area equivalent to all of Western Europe. Two decades later, his administration oversaw one of the most notorious forced labor regimes in human history, leading to the deaths of approximately ten million people—half of the Congo’s population at the time. The international community did not formally commit to the complete abolition of slavery in all its forms until the adoption of the Slavery Convention by the League of Nations in 1926, according to a previous report by Brown University in the United States, which has historical ties to the slave trade.

Due to the multiplicity of actors involved in the trade, it is difficult to obtain an exact figure reflecting the number of Africans transported across the Atlantic. However, estimates from a study prepared by UNESCO’s International Scientific Committee, in a book entitled Africa in Latin America, indicate that between 9 and 12 million Africans were shipped aboard slave vessels from the 15th century to the end of the 18th century, with an annual average of approximately 60,000 people, amid high mortality rates.

The Effects of the Slave Trade

According to the “Policy Brief” jointly prepared by the African Union and the United Nations as part of the “Africa Dialogues 2025” series, the most prominent social, economic, and cultural impacts of the slave trade include:

– Severe demographic disruptions in Africa, often associated with the importation of weapons, which contributed to facilitating political fragmentation across the continent. Cycles of violence and enslavement became self-perpetuating, distorting judicial systems, undermining social trust, and leaving long-term institutional scars within local communities.

– The existence of a direct relationship between the intensity of slave exports from certain African regions and their low income levels in the modern era. Had Africa not been subjected to the slave trade, the average per capita GDP in African countries today would be approximately 72% higher. The regions most heavily depleted of their populations are the very ones that remain the least economically developed today.

The forced displacement of millions of Africans across the oceans enabled colonizers to seize the most fertile lands. Despite land reforms following independence, current patterns of land ownership still reflect those historical confiscations.

The colonial borders drawn during the Berlin Conference divided approximately 177 ethnic groups among several states, creating challenges that undermine political stability and contributing to border and ethnic conflicts, particularly in regions that had centralized political structures before colonization.

According to consistent historical sources, one of the effects of the transatlantic slave trade was the establishment of Sierra Leone and Liberia in West Africa, intended to resettle freed Black people after the American Revolution, in which Africans from the diaspora had participated.

In the early 19th century, thousands of freed Black people settled in Sierra Leone. In 1821, the American Colonization Society established the colony of Liberia, which gained independence in 1847 to become the first independent African republic, with official U.S. recognition in 1862.

Regarding the effects of the slave trade in the Caribbean region—whose countries were largely built upon this trade—a study by Jamaican researcher Nora Waitman in the “Scientific Journal of the Global Justice Network” indicates that the majority of the populations in these countries suffer from poverty, unemployment, and high prices of basic goods compared to Europe and the United States.

The effects of the transatlantic slave trade also extended to the descendants of enslaved Africans, who face various forms of marginalization in host countries.

In Britain, migrants who arrived between 1948 and 1971 from former colonies became known as the “Windrush generation,” named after the ship HMT Empire Windrush, one of the most famous vessels that transported hundreds of African, Indian, and Caribbean migrants to address labor shortages after World War II. With the tightening of immigration and asylum policies between 2008 and 2018, some were detained, denied services, and threatened with deportation before the government acknowledged creating a “hostile environment” for immigrants. A British agreement with Rwanda to deport asylum seekers also drew criticism from the United Nations.

In the United States, the administration of Donald Trump adopted policies aimed at striking deals with African countries to receive deportees, thereby redistributing migration burdens globally.

Africans did not remain passive in the face of racist policies. The African struggle for reparations related to slavery is not new; it dates back to the early years of slavery and colonialism, although it initially emerged within the American diaspora during the American Civil War.

In the New World, this struggle became rooted in the profound impacts of slavery, beginning with the forced arrival of enslaved Africans in the Americas, alongside the exploitation of African resources under colonial rule.

In Britain, demands for recognition of British responsibility and reparations first appeared during the second decade of the 19th century among lower social classes, notably through the Rastafari movement (a religious movement that developed in the 1930s in Jamaica, regarding the Ethiopian emperor as the Messiah and Africans as the chosen people). These demands later acquired a legal foundation defended by political elites in the late 20th century, according to a 2023 study by French researcher Julia Bonacci.

Within Africa itself, social movements calling for reparations began to take shape in the early 1990s, notably through the efforts of Nigerian activist Moshood Abiola—who declared himself the winner of Nigeria’s 1993 presidential election, later annulled—and is regarded as the founder of the “Reparations Movement in Africa.”

In a speech delivered in London in 1992 titled “Why Reparations?”, Abiola called on Western countries to repay their debt to Africa, arguing that the slave trade and colonialism constituted grave injustices requiring full compensation, grounding his argument in both legal and moral reasoning.

Amid the growing momentum of the reparations movement, the Organization of African Unity (later replaced by the African Union) established a committee of eminent persons to follow up on reparations issues at the continental level. Moreover, the World Conference against Racism Durban adopted a proposal stating that the West owes reparations to Africa.

In November 2024, African and diaspora experts called on European governments to confront the past and present consequences of colonialism during the “Decolonial Berlin” conference held in Berlin, presented as an “anti-colonial” version of the Berlin Conference on Africa.

The conference, which included international human rights organizations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, issued a clear list of demands directed at European governments concerning human rights, reparations, migration, the economy, trade, and combating racism.

Opportunities and Challenges

It is not unlikely that Ghana’s anticipated move to revive the issue of the slave trade before the United Nations General Assembly at the end of March will face a mixture of opportunities and challenges, making its diplomatic trajectory dependent on its ability to utilize available legal and political tools.

On the opportunity side, African consensus around adopting the cause strengthens Ghana’s position as one of the primary historical departure points of the transatlantic slave trade from West Africa to the Americas and Europe, granting it symbolic and moral weight in presenting the reparations file internationally.

International principles and guidelines concerning the right to remedy and reparation for victims of gross violations also provide grounds for demanding compensation, rehabilitation, and satisfaction, including official recognition and the preservation of historical memory.

Recent precedents provide additional momentum, such as Germany’s 2021 recognition of the genocide committed against the Herero and Nama peoples in Namibia, along with a financial package to support development projects—a step considered a precedent in addressing the legacy of colonialism, despite debate over its legal characterization.

Conversely, structural obstacles remain, foremost among them the difficulty of achieving international consensus on historical issues with complex moral and legal dimensions, particularly in the absence of a clear willingness among Western powers to assume direct legal responsibility for crimes committed centuries ago.

Deliberations at the World Conference against Racism Durban in 2001 reflected deep divisions over classifying slavery and colonialism as crimes warranting reparations. Canadian scholar Rhoda Howard-Hassmann notes in her book Reparations to Africa that African claims face challenges related to the death of original victims, the vast numbers involved, and the complexity of identifying beneficiaries, compared to other historical cases with clearer legal frameworks.

Additionally, some Western capitals fear the politicization of the issue amid intensifying competition in West Africa, marked by the growing presence of Russia and China in the region. There are concerns that the reparations issue could become a tool of political leverage in the reshaping of international alliances, potentially prompting greater caution or resistance to reviving the transatlantic slave trade file.

The issue also intersects with contemporary policies adopted by some European countries and the United States, including so-called “safe third country” agreements. Observers argue that such policies reflect the persistence of historical power imbalances between the Global North and South, potentially complicating the political climate needed to advance reparations claims.