What You Need to Know

Tensions between Ethiopia and Eritrea have resurfaced, particularly surrounding the Eritrean port of Aseb. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s remarks about access to the sea have been interpreted as a threat to Eritrean sovereignty, prompting a strong response from Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki.

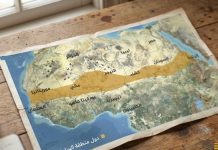

Africa. After just two years since the end of the Tigray War, tensions between Ethiopia and Eritrea have resurfaced, this time through the lens of the Red Sea, where the Eritrean port of Aseb has reignited historical disputes between the two countries.

The coastal city, located only 60 kilometers from the Ethiopian border, has become a renewed symbol of sovereignty and national identity, as well as a stage for escalating regional tensions, according to a report from a local source.

In October, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed sparked widespread controversy when he stated in parliament that “Ethiopia’s access to the sea is a matter of survival,” considering the deprivation of a maritime outlet a “historical, geographical, and legal injustice.”

This statement, which some interpreted as a call for regional integration, was perceived in Asmara as a veiled threat to national sovereignty, as reported by the local source.

Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki quickly responded, asserting in a television interview that “the security of the Red Sea is a matter that concerns only the coastal states,” clearly rejecting any Ethiopian role in managing this vital corridor.

The report indicates that this divergence in rhetoric reflects the deep chasm between the two nations, despite the peace agreement signed in 2018.

Historically, Aseb Port was the economic lifeline for Ethiopia, accounting for over 90% of its foreign trade before Eritrea’s independence in 1993. It housed the only oil refinery in the country, making it, as researcher Brook Hailu states, “more than just a port; it is a symbol of Ethiopian economic sovereignty.”

However, after the rise of the Ethiopian Revolutionary Democratic Front to power, the perspective on ports shifted, viewing them as negotiable commercial tools rather than sovereign rights.

Legal scholar Tilahun Adamu notes that the Ethiopian leadership at that time squandered a historic opportunity to maintain a foothold in Aseb or even negotiate over it, leaving the issue unresolved.

Today, this matter has resurfaced, driven more by internal political factors than geographical ones. The Ethiopian government, as highlighted in the report, seeks to leverage the narrative of “the sea as an existential right” to rally public support and bolster its position domestically amid increasing economic and security challenges.

Conversely, Eritrea remains steadfast in its position that there can be no discussion about sovereignty over ports, and any arrangements with Ethiopia must occur through clear bilateral agreements.

The irony, as the report notes, is that Aseb Port itself has been stagnant since the border war (1998-2000), with aging infrastructure limiting its capacity to play an effective economic role.

Maritime expert Hamidi Abdi warns that the dispute over Aseb transcends logistical disagreements, evolving into a matter of national identity and a regional pressure point.

He adds that any attempt to revisit the issue without genuine consensus could lead to a diplomatic crisis or even direct confrontation.

In this context, additional complexities arise, particularly the Sudanese crisis, which African officials described during recent migration meetings as “one of the most complex humanitarian crises on the continent.”

The report indicates that the lack of humanitarian access and the difficulty of delivering aid in Sudan reflect the fragility of the regional structure, complicating any collective initiatives for governing the Red Sea or managing border disputes.

Moreover, the absence of effective regional mechanisms for conflict resolution and the proliferation of external mediation pathways weaken the African Union’s ability to contain tensions.

The local source emphasizes that managing the Aseb issue is inseparable from a broader crisis concerning the balance of power in the Horn of Africa, where national interests intersect with the legacy of wars and separations, amid a lack of a shared vision for the region’s future.

Ultimately, Aseb remains more than just a port: it is a historical knot, a symbol of sovereignty, and a constant testing point for the fragility of peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

As Ethiopian demands escalate and Eritrea clings to its positions, the Red Sea remains an open stage for potential escalation or détente.

Historically, Aseb Port has been vital for Ethiopia, handling over 90% of its foreign trade before Eritrea’s independence in 1993. The port housed the only oil refinery in the country, making it a symbol of Ethiopian economic sovereignty. However, after the rise of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, ports were viewed as negotiable assets rather than sovereign rights.

The 1998-2000 border war between Ethiopia and Eritrea led to a significant deterioration in relations, with Aseb’s infrastructure suffering from neglect.