What You Need to Know

On November 23, 2025, Ethiopia’s Haili Gubi volcano erupted, sending an ash and gas column nearly 14 kilometers high. This unusual activity has raised concerns about economic impacts on local herders and disrupted air travel across thousands of kilometers. Satellite imagery shows widespread ash dispersion affecting regions as far as Pakistan and northern India.

Africa. On Sunday, November 23, 2025, the Haili Gubi volcano in the Ethiopian Afar region erupted for several hours, releasing a column of ash and gas reaching nearly 14 kilometers in height, sufficient to impact commercial air travel.

Ash clouds covered many surrounding villages, and local officials warned of severe economic consequences for herders due to the choking of grazing lands.

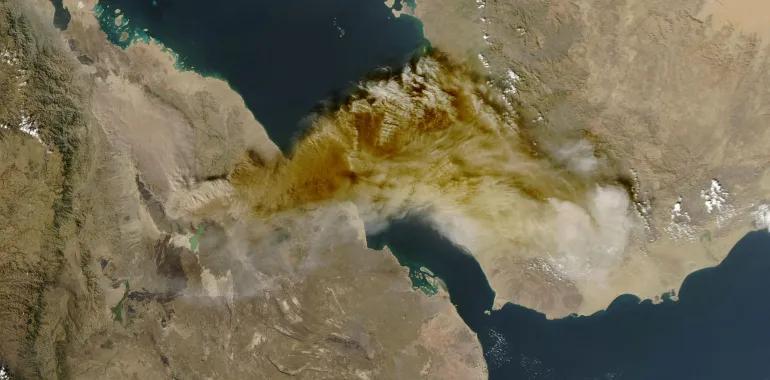

On a broader scale, satellites monitored the extensive spread of volcanic ash, leading to international warnings and disruptions in air travel thousands of kilometers away, as the ash cloud drifted eastward across the Red Sea towards the Arabian Peninsula and into parts of Pakistan and northern India.

Location and Type of Haili Gubi Volcano

Haili Gubi is situated in the northeastern part of Ethiopia, near the Eritrean border, and is part of the larger Danakil-Afar depression, which hosts some of Africa’s most active volcanoes. It is classified as a shield volcano.

Shield volcanoes have broad, gentle slopes and resemble a “stretched shield” on the ground, rather than a steep-sided cone like some other volcanoes. They are primarily formed from repeated flows of low-viscosity basaltic lava, which can travel long distances before cooling and solidifying, creating extensive layers over time.

Haili Gubi lies within the East African Rift, a region where tectonic plates are slowly pulling apart. As the plates move apart, the Earth’s crust stretches and thins, allowing hot rocks from the mantle (the layer beneath the crust) to rise.

When these rocks rise, the pressure on them decreases, causing them to partially melt and form magma that can either travel through fissures or erupt from vents to feed the volcanoes.

Volcanologist Ariana Soldati estimates the rate of plate divergence in the area at about 0.4 to 0.6 inches per year; while this is a small amount in human terms, it is significant over thousands and millions of years and could eventually lead to the formation of a new ocean basin.

Why Is This Eruption “Strange” for a Shield Volcano?

Typically, shield volcanoes do not erupt violently; they tend to erupt quietly, with lava flows that ooze and cascade down their slopes. Therefore, the unusual aspect of the Haili Gubi eruption was the massive ash column that rose to about 14 kilometers into the sky, creating a canopy-like cloud, which is atypical behavior for this type of volcano.

Several possible explanations could account for this phenomenon, and more than one may have occurred simultaneously:

First, the magma may have been gas-rich, or gases may have accumulated for a long time in a system that was nearly closed due to dormancy for thousands of years. When the pathway suddenly opened, the pressure dropped rapidly, causing the magma to fragment into tiny particles that turned into ash instead of flowing lava.

Second, if the rising magma encountered groundwater or hot liquids underground, a violent reaction could occur as the water rapidly turns to steam, fragmenting the magma and increasing ash production.

Third, at the onset of any volcano’s reawakening, the eruption may be “dirty,” meaning it uproots older materials from rocks and deposits within the volcanic conduit, increasing ash and dust.

Fourth, sometimes the nature of the magma itself may change (through mixing or chemical evolution), increasing its viscosity and making it more prone to explosive eruptions rather than quiet flows.

Why Is It Erupting Now?

Haili Gubi is typically described as dormant since the beginning of the Holocene epoch, approximately 11,700 years ago, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program. However, the absence of known eruptions does not necessarily mean there have been no volcanic activities; this volcano has not been studied extensively and is located in a remote area. Therefore, limited monitoring and fieldwork may overlook small or short-lived events that could provide signals or a clearer understanding of the current eruption’s nature.

Some volcanic eruptions may be weak, leaving thin layers of ash that are quickly erased by winds and rains, or they may be local and go unnoticed, or occur in sparsely populated areas, thus escaping documentation. Even their geological effects may be buried under newer sands or lava flows or distorted by erosion.

Thus, in remote areas like parts of Afar, a volcano may remain “silent on paper” for centuries or thousands of years, only to surprise everyone with a significant eruption, not because it emerged from nowhere, but because we lacked regular monitoring to reveal the small signs that precede eruptions or document limited events that may have actually occurred.

What Is the Expected Impact in Ethiopia?

Local impacts in Ethiopia include widespread ash fallout affecting livelihoods. Officials reported no immediate injuries, but they confirmed the ash’s density in villages and the threat it poses to ash-covered pastures. In this context, animals “find nothing to eat,” and herders may have to relocate, purchase feed, or sell livestock under these pressures.

Additionally, ash fallout may have side effects that could worsen over days or weeks, such as water contamination when ash falls into tanks and wells, especially in arid areas where clean water supplies are already fragile.

Moreover, respiratory and eye irritation may occur, particularly among children, the elderly, and anyone with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The ash is abrasive, clogging filters, damaging moving parts in factories, transportation means, and equipment in general, and it may cause electrical short-circuits in electrical devices when wet.

International Impact and Reach: Where Does It Go?

Cross-border transport follows a path monitored by satellites, starting from the Red Sea to Yemen and Oman primarily, then to Pakistan and India, as indicated by the Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Center, which tracks the cloud through satellite imagery.

By Tuesday, Reuters reported that ash had covered parts of Pakistan and northern India after crossing Yemen and Oman, with the cloud heading towards China.

This long-range drift is primarily related to the volcano’s height and the nature and direction of the winds, as the ash is released at a sufficient altitude to allow air currents to carry it over long distances.

Consequently, Reuters reported that Indian Airlines canceled flights for precautionary checks on aircraft following a directive from regulatory authorities, while Akasa Airlines canceled some flights to the Middle East; the Indian Meteorological Department predicted that the ash would clear from the skies over India by Tuesday afternoon.

Media reports indicated that the Pakistan Meteorological Department issued a warning after ash entered its airspace.

Volcanic ash is considered a severe hazard for airlines, as it contains abrasive glass particles that can melt inside aircraft engines and solidify again, weakening performance and leading to loss of thrust, as well as causing wear on windows and sensors.

What Are Scientists Focusing on Now?

Based on what has been reported, urgent scientific priorities include answering several questions: Is the volcano’s system still leaking magma? Satellites are interested in studying ground deformation to determine whether the activity is still ongoing.

Another important question is: What is the amount of sulfur dioxide and ash being emitted, and at what altitudes? Answering this question will clarify the health risks and aviation hazards associated with this type of volcano.

Overall, the Haili Gubi volcano represents a case study of how shield volcanic activity, combined with limited monitoring, and strong winds, can transform an unlikely volcanic eruption into a disruptive event across multiple regions.

The Haili Gubi volcano is located in the Afar region of Ethiopia, part of the East African Rift system, where tectonic plates are slowly diverging. This geological activity has made the area one of the most volcanically active regions in Africa. Historically, the volcano has been considered dormant, with no significant eruptions recorded in the Holocene epoch, which began approximately 11,700 years ago. However, the lack of documented eruptions does not imply inactivity, as the region’s remoteness has limited scientific observation and data collection.